Early ElectroMIX is a series to document the history of experimental Electronic music from the 50s to the 80s, composers making use of electronic instruments, test equipment, generators of synthetic signals and sounds… to analog synthesizers…While our sessions document those who make it today my desire is to transmit some pioneering works which paved the way to what we try to create today.

Realizing that most of those seminal recordings were not available I decided to archive them in a contemporary way, DJing-mixing them and while most of the time running several sources together or in medleys I made sure to respect the original intent of each composers as I want to transmit their message rather than mine.

The only one I would dare deliver being that they should not be forgotten…

Philippe Petit / April 2021.

Recorded (March 17/2021) for our series broadcasted on Modular-Station

Tracklist:

Kenneth Gaburo – Fat Millie’s Lament / 00:00 > 04:34

Georges Teperino – Cosmic Sounds V / 00:06 > 02:30

Bernard Parmegiani – Outremer / 03:28 > 25:50

Georges Teperino – Cosmic Sounds II / 04:52 > 06:48

Karlheinz Stockhausen – Gesang der juenglinge /18:47 > 32:01

Léo Kupper – Electro-poème / 31:55 > 37:36

Morton Subotnick – Touch pt.1 / 36:48 > 51:36

Todd Dockstader – Water Music / 51:22 > 54:48

Bülent Arel – Postlude from Music for a Sacred Service / 54:48 > 58:38

Todd Dockstader – Electronic Piece 1 / 58:00 > 01:00

Kenneth Gaburo – Fat Millie’s Lament (1965 / Pogus)

Kenneth Gaburo was a US composer, but also a teacher, conductor, writer, and publisher, working at the University of Illinois in the mid-1960s, at the University of California at San Diego during the 1970s, and finally at the University of Iowa, where he directed the Electronic Studios in the 1980s and early 1990s. Fat Millie’s Lament appeared in 1965 and the piece is a collage including tape loops, speed changes, and quotations from a big-band piece by his friend Morgan Powell.

Georges Teperino – Cosmic Sounds V (1969 / TVMusic)

Georges Achille Teperin was a French musician & electronic pop pioneer who also recorded under the name Nino Nardini.

At the very beginning of the Sixties he entered the world of Music Library in collaboration with his old childhood friend Roger Roger and thy build up the Studio Ganaro, a personal recording space where they started to work together on composing many kind of music and then heavily experimenting on the moog synthesizer and other analogue electronic systems. In particular,Teperino was the one heavily oriented to innovative experiments with musique-concrete blended with common concert instruments.

Bernard Parmegiani – Outremer (1975 / La Voix De Son Maître)

Parmegiani initially studied mime, and then worked as a television sound engineer, but decided to work under Schaeffer at his then newly formed musique concrète research group, the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM), in Paris and shortly was put in charge of the Music/Image unit for French television (ORTF). While there he worked with Iannis Xenakis, François-Bernard Mache and many other early experimental composers.

He composed numerous seminal works for tape, electroacoustic and this piece for Ondes-Marthenot and controlled feedback shouldn’t be neglected.

Georges Teperino – Cosmic Sounds II (1969 / TVMusic)

Another shorty from that split with Cécil Leuter…

Karlheinz Stockhausen – Gesang der juenglinge (1956 / Chrome Dreams)

This one was realized in 1955–56 at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk studio in Cologne and integrates electronic sounds with the human voice by means of matching voice resonances with pitch and creating sounds of phonemes electronically. In this way, for the first time ever it brought together the two opposing worlds of the purely electronically generated German elektronische Musik and the French musique concrète, which transforms recordings of acoustical events.

Gesang der juenglinge meaning « Song of the holy children » aimed at forming a link between language and music by means of the following elements: vowels – sinus, sounds, consonants – bands of noise and plosives – impulses. The composer had acquired the requisite knowledge when he studied communication theory and phonetics under Meyer-Eppler in Bonn. Work on the Electronic was based on the idea of combining sung notes with electronic notes: they were to be as fast, as long, as loud, as soft, as dense and as interwoven, with as small or as large intervals of pitch, and with as differentiated tone-color nuances as the imagination demands.

Karlheinz Stockhausen was a German composer, known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music, for introducing controlled chance (aleatory techniques or aleatoric musical techniques) into serial composition, and for musical spatialization. At the time of composing this work Stockhausen was a devout Catholic and his original idea was for a mass that included voices and electronic sounds but the church authorities made it clear that loudspeakers were unacceptable in their sacred building. Despite this setback Stockhausen decided to set a Biblical text, the Burning Fiery Furnace, from the Book of Daniel.

Robert Worby wrote about the making Gesang der Jünglinge :

This passage was cut into phrases, words, syllables and phonemes which were sung by Josef Protschka, a 12 year old chorister. These fragments were edited further and formed into, what Stockhausen called, ‘swarms’ of voices which were combined with electronic sounds created using the extremely primitive studio tools.

This whole process was extremely laborious and it took well over a year to make a piece that lasts just over 13 minutes. Stockhausen had two or three assistants each performing separate tasks: one controlled the speed of clicks on the impulse generator, another turned dials on the filter and a third controlled the overall volume of the resulting sounds. They recorded again and again until the contours of the swarms were exactly right. Some of this material would be processed with reverberation – created by a large metal plate or sometimes a cavernous room underneath the studios – projecting the sounds into vast, empty space.

All of these results were spliced together onto audio tape and then several tapes would be mixed onto one to create even more complex material. And so bit by bit, centimetre by centimetre, Gesang der Jünglinge was formed. It’s actually unfinished. Stockhausen planned seven sections but there was time to complete only six. When, in 2001, I asked him why he didn’t finish it, he pressed his lips together then said, in his inimitable Cologne accent, ‘They wanted a concert.’ A date had been scheduled and when that date came he presented work in progress. And so it has remained to this day. Right at the end of the piece, there’s a moment’s silence followed by a final burst of electronic sound. This final burst is the beginning of section seven.

Léo Kupper – Electro-poème (1963 – 1970 / Deutsche Grammophon)

Leo Kupper from Belgium was one of the European pioneers of electronic music. Influenced by Luciano Berio’s “Omaggio a Joyce”, this creation is for a mixed choir of twelve actors/singers. Kupper worked with the late composer Henri Pousseur in the first electronic music studio in Belgium and, from the 1960s, was the founder and director of the “Studio de Recherches et de Structurations Electroniques Auditives” in Brussels.

Over the next decade, he discovered the music of Iranian master Hussein Malek, and developed a passion for the latter’s instrument, the Santur, of which he was one of the Western virtuosos.

He is also a poet and has a new book in preparation.

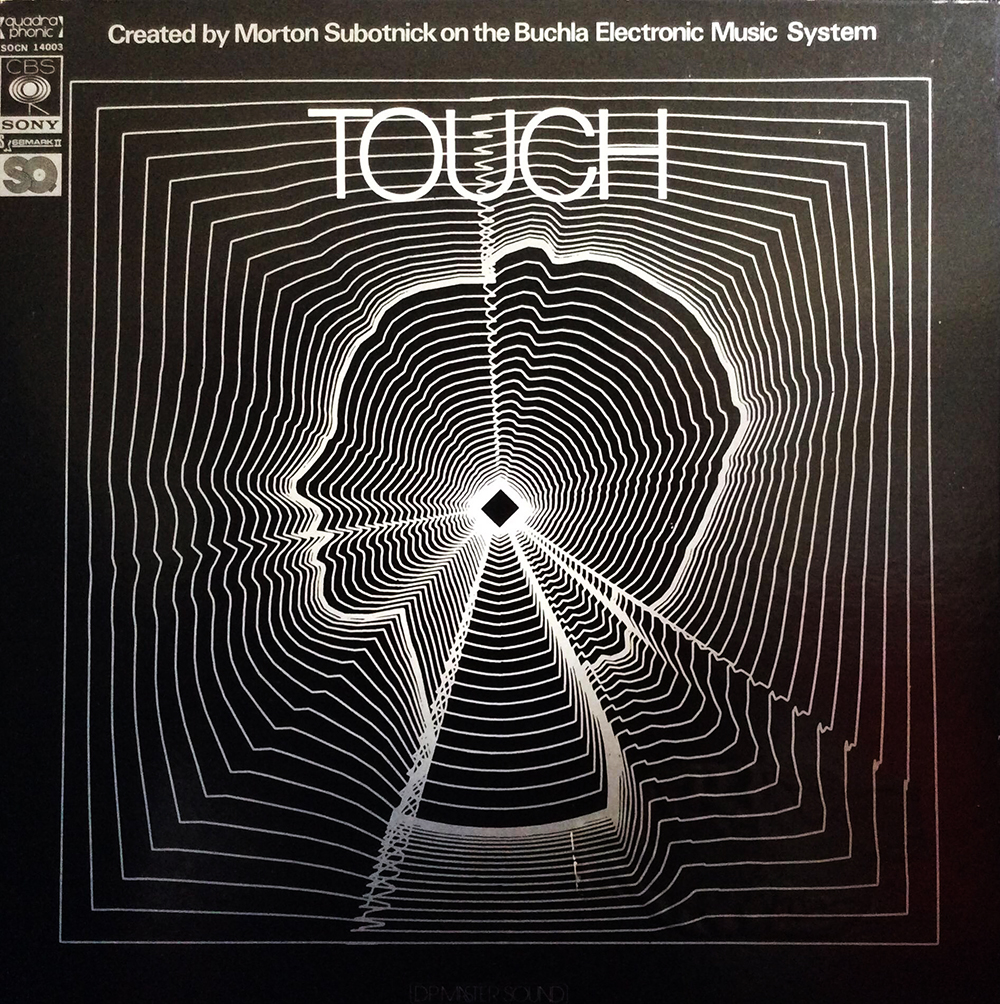

Morton Subotnick – Touch pt.1 (1969 / Columbia Masterworks)

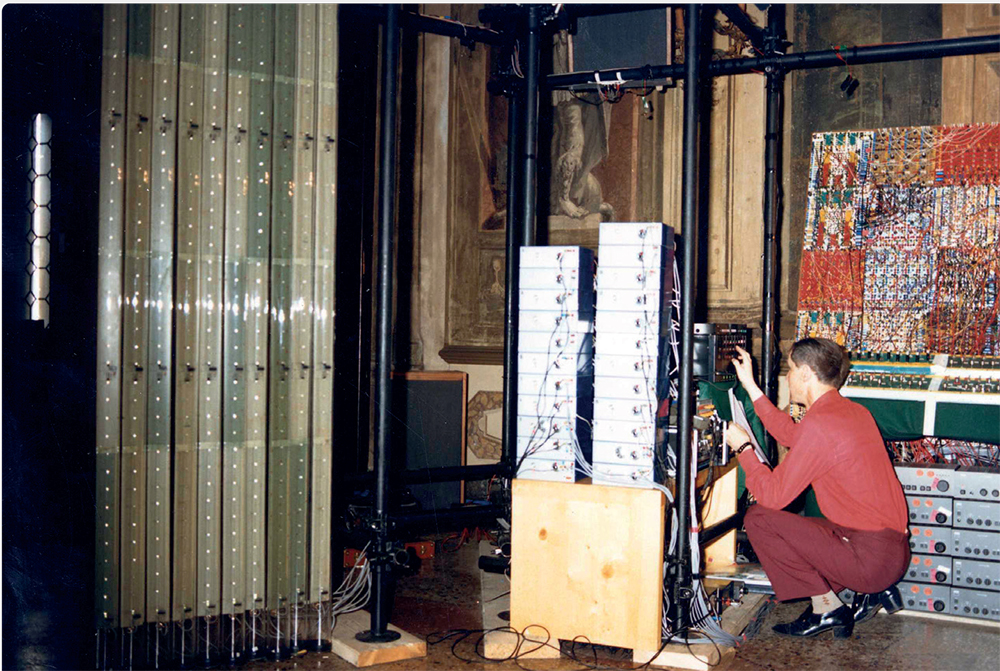

Morton Subotnick was one of the founding members of California Institute of the Arts, where he taught for many years. In the 60s he co-founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center with Pauline Oliveros and Ramon Sender, where they directed Don Buchla to invent and instrument for them paving the way to the most thought-provoking Modular Synthesizers. This abstract piece – dramatically paced and structured – was composed on a Buchla 100 system operated by his voice in an enveloppe follower. Third album from the Maestro, following Silver Apples of the Moon (1967) and The Wild Bull (1968) which is a personal favorite. These recordings happened after Subotnick had moved to New-York to become musical director for the Lincoln Center Repertory Theater, and also he became one of two artists-in-residence at New York University’s School of the Arts. Subotnick was joined by two artists-in-residence: first, kinetic sculptor Len Lye, and for the second academic year, visual artist Tony Martin who had been his colleague at the San Francisco Tape Music Center. Reunited in New York, Subotnick and Martin also collaborated in the development of the multimedia sound and light shows of the Electric Circus, a Greenwich Village discotheque.

The New York University provided an off-campus studio built around the Buchla, upstairs from the Bleecker Street Cinema in the center of Greenwich Village. This was a neighborhood of cafés and folk, rock, and jazz music venues. Notable artists living or performing in the neighborhood visited the studio, among them Andy Warhol’s associate Isabelle Collin Dufresne (Ultra Violet), members of the Grateful Dead, Lothar and the Hand People, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and Angus MacLise, Maureen Tucker, and other figures connected with the Velvet Underground, even Steve Reich also stopped in.

Subotnick recollects: “I was really a celebrity in New York for a couple years and the studio became a famous underground thing that suddenly hit the news. People felt like they were part of something. It was a big moment in their lives and they’ve hung onto it in ways that I’ve forgotten. I moved along and kept being me. New York is the marketplace for the arts. It’s not a place where young people could easily experiment because anything you did took on an importance that would tend to squelch a kind of freethinking [and experimentation]. It was the whole scene that makes individuals capable of doing what they do… During that period, New York was really hot. Even if everything you did wasn’t out there for everyone to know, you imagined that it was.”

In retrospect, one of the most important features of Subotnick’s residency was his use of young studio assistants. This act of generosity sparked and nurtured the early composing careers of Maryanne Amacher, Rhys Chatham, Michael Czajkowski, Brian Fennelly, Ingram Marshall, Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, David Rosenboom, Laurie Spiegel, and others, among them composer/instrument builder Serge Tcherepnin.

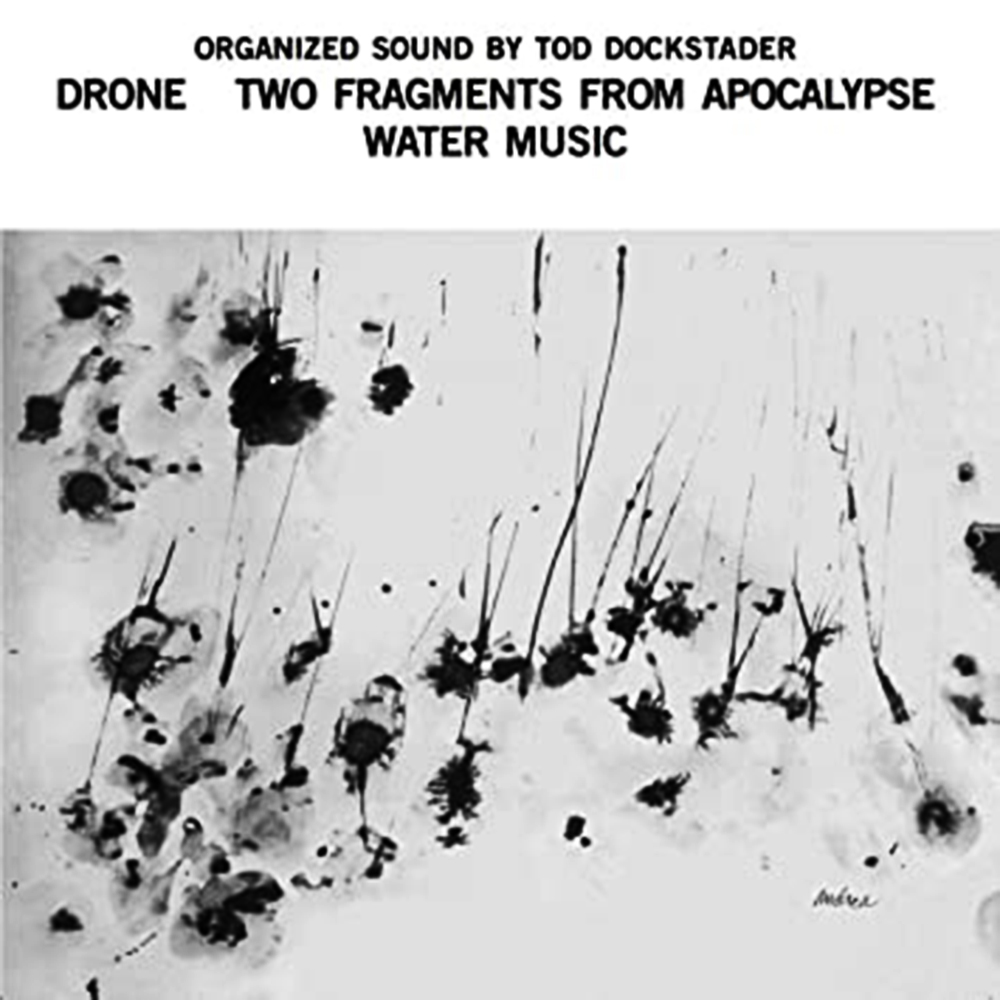

Todd Dockstader – Water Music (1963 / Owl)

First of all allow me to emphasize that to me Todd Dockstader needs be remembered as one of those few innovative, visionary composers. Back in 1963 his “organized sound” had captivated only a few listeners and he had moved to Los Angeles, where his drawing skills landed him a job as a film editor, writer, and production designer at UPA studios in Burbank. It turned out that a film editor in a small studio was also expected to cut a lot of sound, as well as create sound effects needed for cartoons, and editing sounds. Cartoons he cut sound and picture for included “Mr. Magoo” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” Doing sound effects at New York’s Gotham Recording in the early 60s and for a decade went on working principally with tape manipulation effects. His years at Gotham (1958 – 1966) were highly productive. He spent long hours there, when the studio was closed, creating his now classic tape works, including: Luna Park, Apocalypse, Water Music, and Quatermass. His last piece at Gotham was Four Telemetry Tapes in 1965.

Early synthesizers did not appeal to Todd. He recalled that, in 1964 :

I got a letter from someone named Robert A. Moog, inviting me to look at his new ‘instruments for electronics music composition’—his words—at the AES convention in New York. How he got my name, I don’t know; this was before my LPs came out. So, I went, I looked, I saw a keyboard and a prototype wall of knobs and wires. I listened, and I got a sinking feeling that my kind of music was ending here. My peculiar skills were going to be obsolete, like a blacksmith looking at his first automobile. That keyboard: that meant the writers were going to take over electronic music. And so, we got Switched-On this-and-that and Dancing Snowflakes and all, in just a few years.

Water Music began with the sound of water; there is little else in the piece. Water Music had its premiere on WXQR in June 1963. At the end of the broadcast, the announcer stated that, since electronic music wasn’t going anywhere, the broadcast would be the last of its kind. They’d also played Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge – so It went out in good company.

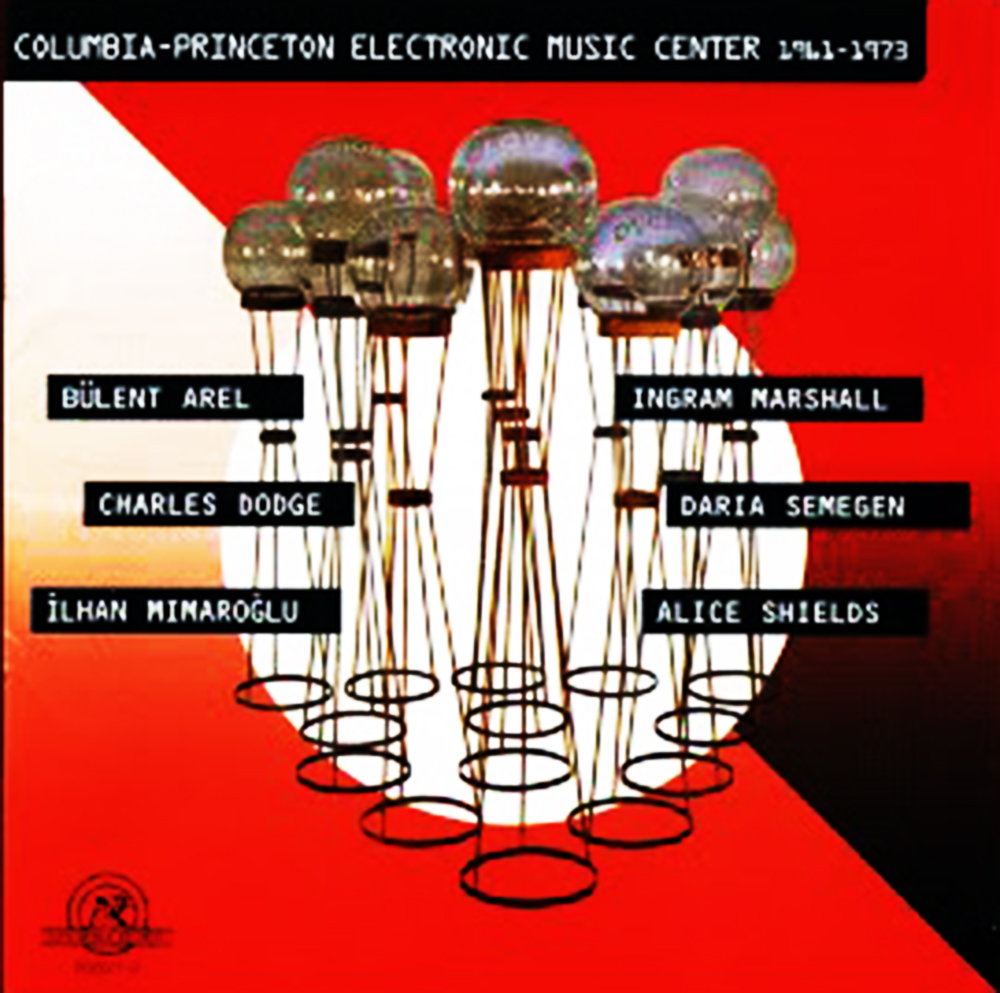

Bülent Arel – Postlude from Music for a Sacred Service (1961 / New World)

Bülent Arel was born in Istanbul, and studied composition at the Ankara Conservatory and sound engineering in Paris.

In 1959, the Rockefeller Foundation invited him to work at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. In 1962, he worked with Edgard Varèse on the electronic sections of Varèse’s Déserts.

He also designed and installed the electronic music laboratory at Yale University, where he taught from 1961 to 1970, and he established the electronic music program at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, where he taught from 1971 until his retirement in 1989.

Besides electronic works, Mr. Arel wrote chamber music, vocal works, and symphonic pieces, including a series of works commissioned by the Mimi Garrard Dance Theater. In the course of his work he invented the ‘splicing tape dispenser’, as well as other devices for tape handling. He was a pioneer of looping techniques.

Todd Dockstader – Electronic Piece 1 (1961 / Folkways)

Eight Electronic Pieces is a foundational document of American electronic music and a stunning first work from this revolutionary composer made when he worked as a recording engineer at New York’s Gotham Recording. At this major commercial studio, he surreptitiously used off-work hours to collect and experiment with interesting sounds.

Up to 1960, Tod had not heard much musique concrète. He recalled:

“I don’t think I modeled my first work after anyone in particular, not consciously anyway. I just knew how to do it.”

Around that time, Todd created Eight Electronic Pieces. Years later, Fellini used parts of these in his “Satyricon”…