Early ElectroMIX is a series to document the history of experimental Electronic music from the 50s to the 80s, composers making use of electronic instruments, test equipment, generators of synthetic signals and sounds… to analog synthesizers…While our sessions document those who make it today my desire is to transmit some pioneering works which paved the way to what we try to create today.

Realizing that most of those seminal recordings were not available I decided to archive them in a contemporary way, DJing-mixing them and while most of the time running several sources together or in medleys I made sure to respect the original intent of each composers as I want to transmit their message rather than mine.

The only one I would dare deliver being that they should not be forgotten…

Philippe Petit / September 2021.

Recorded on 22/05/2022 for our series broadcasted on Modular-Station

https://modular-station.com

Tracklist:

Bent Lorentzen · Electronic Music (Medley) (1987 / Point) 00:00 > 14:50

Ragnar Grippe – Sand (1977 / Shandar) 12:00 > 32:11

Teresa Rampazzi – With the Light Pen (1976 / Die Schachtel) 31:51 > 39:55

Herbert Eimert, Robert Beyer – Klangstudie II (1952 / Sub Rosa) 39:36 > 44:04

Todd Dockstader – Tango (1966 / Owl) 43:50 > 51:08

François Bayle – Jeîta (1971 / Philips) 49:56 > 59:24

Bent Lorentzen · Electronic Music (Medley) (1987 / Point)

Bent Lorentzen is widely considered one of the key figures and pioneers of early Danish electronic music and he was one of a few classically trained composers seeking out the possibilities of the new technology in the 1960’s. Lorentzen composed a fairly large number of electronic works and developed a significant educational practice in and around electronic music, conducted workshops, taught at courses, and published articles in both national and international journals, while also producing several educational records on electronic music.

‘Electronic Music’ was originally released in 1987 as a retrospective album, collecting three of Bent Lorentzen’s electronic works from the Seventies.

The music is often quite dramatic with distinct narratives and multiple dynamic layers of sound, but still with a clear sense of disposition and restraint, possibly stemming from Lorentzen’s experience with classical instrumentation, and orchestration.

Ragnar Grippe – Sand (1977 / Shandar)

Originally trained as a classical cellist, Grippe had relocated to Paris in the early 70’s to study at the famous GRM. There he had struck up a close friendship with French avant-garde minimalist Luc Ferrari. It was under Ferrari’s direction and guidance that the young Grippe started to build a shared experimental music studio, aptly named l’Atelier de la Libération Musicale (ALM, meaning « A workshop for musical freedom » ), in which Ferrari shared his knowledge and instrumental supplies, thus forging Grippe’s implementation of harmonic tone within the confines of musique concrete.

One of the visiting artists passing through the creative epicenter of the Cité Internationale des Arts during this time was the painter Viswanadhan Velu. Velu’s recent works consisted of various Sand paintings which were to be exhibited at the Galerie Shandar, the avant-garde art gallery and home to the Shandar record label which was the home to minimalist composers Terry Riley, La Monte Young, Cecil Taylor and Charlemagne Palestine.

Grippe was asked to compose a piece that was to be played during the Sand painting exhibition and was then to be released on the Shandar imprint in 1977.

Teresa Rampazzi – With the Light Pen (1976 / Die Schachtel)

Teresa Rampazzi was an Italian composer/musician. Founder of the “NPS-Nuove Proposte Sonore” experimental music collective, inspirer and one of the chief protagonists of the “Centro di Sonologia Computazionale ».

In 1952 she participated to the Ferienkurse für Neue Musik at Darmstad. At that time she was a pianist, performer of avant-garde music and chorus singer; she was married with 2 children.

The 1952 edition was one of the most famous edition where Eimert showed to the public a small frequency generator. Musicians looked at it suspiciously and did not attach too much importance to it. For Tereza, that little, tricky object could certainly grow, multiply, shock the musical world.

Teresa comes back in Padova changed:

…you cannot ask a newborn baby to make a long speech. I started to babble when I enthusiastically decided to use the [Eimert’s generator]. I mixed just short signals for some few minutes. They were not phrases nor words. I shut down and sold the piano, though I’ve almost destroyed it during my performances with John Cage. And I bought the same little frequency generator I’ve seen at Darmstadt. With it and a mono tape recorder, I tried to make my first electronic experiment.

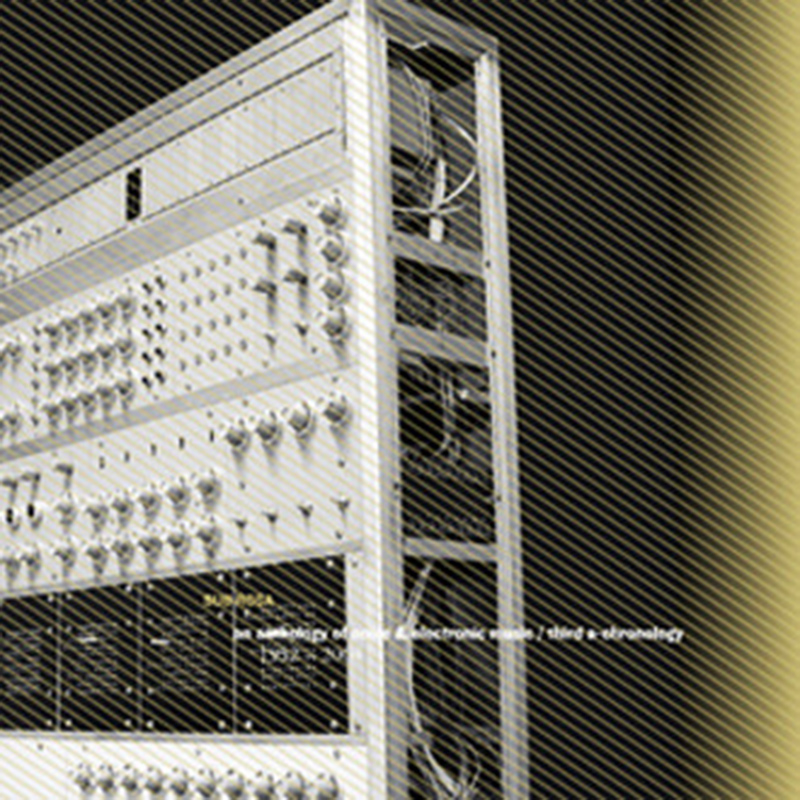

Herbert Eimert, Robert Beyer – Klangstudie II (1952 / Sub Rosa)

Herbert Eimert was a composer and a musicologist who studied at the Music Conservatory of Cologne and at Cologne University. He worked as a journalist and joined the NWDR station as a music editor and programmer. By 1948 he was in charge of the nighttime programming and one can imagine the impact these new musics he was airing had on young nocturnal listeners…

Together with sound engineer colleague Robert Beyer, he succeeded in founding The Studio for Electronic Music of the West German Radio, a facility of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk – WDR in Cologne).

From 1953, Eimert invited Karlheinz Stockhausen & Gottfried Michael Koenig to work in the studio which he directed until 1962. He wrote books on Dodecaphonic and Serial music. In 71 he had started a Dictionary of Electronic Music but the manuscript was not completed before his death in 1972.

Todd Dockstader – Tango (1966 / Owl)

Being an outsider without academic credentials, Todd Dockstader was denied grants and access to the major electronic music centers and luckily managed to get contracted in the movies industry and work on some Library deals…

It’s now been decades that he is in the electronic music pantheon alongside Varèse, Stockhausen, and Subotnick to name but a few and his “organized sounds” have captivated, delighted, and sometimes frightened connoisseurs all over the World. Many have considered « Starkland » as a musique concrete masterpiece, so better allow the composer offers some thoughts about his extraordinary work:

Quatermass was intended, from the start, to be a very dense, massive, even threatening, work of high levels and high energy. It was my antidote to the preceding Water Music – a work of small details, delicate textures, and some playfulness… As with all my pieces, work began with collecting what I call ‘cells’ (Schaeffer called them ‘sound objects’): hours and hours of quarter-inch tape recordings of whatever interested me, the original sound transmuted with (what are now called) ‘classical’ tape-studio techniques.

By the time I did Quatermass, I guess I had a library of around 300,000 feet of tape (125 hours at 15 ips). From this mass, I would select cells that seemed like they might work together into a piece, and then turn them into stereo (with more classical techniques of tape-delay and tape-echo between channels, panning, reverberation, and placement). For Quatermass, I had, for the first time, use of a three-track recorder (the third track filled the center ‘hole’ in early stereo recording), which allowed me to do more complex tape-echo rhythms than before which one may hear in ‘Tango’ which – although it doesn’t start like a tango – becomes something like a tango

I think I was aided, in my time and circumstances, by not having a synthesizer of any kind: no keyboards, no pre-set voices.

Playing one or two sine-wave test generators (“oscillators” we call’s today) which were “played” by turning a dial. I forced them to produce harmonics (square waves) by amplifying them into distortion, and got pulse-trains out of them by temporarily rewiring them into instability (temporarily, because they had to resume life the next day as stable test generators). The “notes” they produced were achieved by editing tape, note by note (by note by note…). Also, when turned on or off, it made marvelous shrieks and groans.

Some composers who worked in what’s been called the “glorious junkshop” of the now-classic tape studios have looked back in awe and dismay at the amount of hard, physical work it took to make a piece. But easier isn’t necessarily better. I enjoyed it: I found it was like the best part of painting – standing on your feet all day, moving around, working with your hands, sometimes very fast, more often very slowly, mixing, cutting, stitching it together with the sound in your ears. It had a muscular joy to it. I think a lot of us had fun up on that singing high wire, teetering between control and chaos, trying to push the sound a little farther toward Something we hadn’t heard before, working in it… Listening.

In the mid 2000s, Dockstader’s health diminished, but he continued composing until dementia stopped him.

He died peacefully on February 27, 2015, listening to his music.

François Bayle – Jeîta (1971 / Philips)

Sound has no form, it is invisible. Our ear gives form to sound. Sound is the mark of dynamic, invisible, ghostly beings that move around us, that have a will, that approach us. Our ear, the organ of survival, detects them instantly, precisely because they are invisible. We listen to what is going to happen. This is what interests me and what makes acousmatics for me a wonderful gift of technology to our intelligence.

The art of sound lacked the ability to be written, but not with notes or words. To write sound is to capture it and hold it

François Bayle has just turned 90 and still devotes himself to research and composition. A living legend who started out as a composer in the 1960s, and trained with Karlheinz Stockhausen, Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Schaeffer and was put in charge of the GRM in 1966, first with P. Schaeffer (Research Department) and then with the INA (National Audiovisual Institute) in 1975. It was through these organisations that he created the Acousmonium and the current of acousmatic music creation. In the GRM studios, more than a thousand concerts and regular broadcasts on France Musique have been produced. François Bayle directed the INA-GRM record collection thru which “Jeita” and so many other seminal works wre published.

The discoverer of the Jeîta cave near Beirut in Lebanon, Sami Karkabi, asked the composer of “Uninhabitable Spaces” to write music for its inauguration in 1969. This was Nadir, 1968 (cat. 37), for soprano, tenor, bass, bass clarinet, guitar, ondes Martenot and percussion, which was premiered in the cave on 11 January 1969, conducted by Konstantin Simonovic. On this occasion, François Bayle took sound recordings in the very space of the cave (percussion on the stalactites, rustling of the water, etc.) which are the starting point for this suite.

Jeîta, whose name means “murmuring waters” in Aramaic, questions the paradox of this intimate and nocturnal conjunction between hardness and fluidity. To this very slow elaboration and transmutation of a fluidified stone and petrified water, this music responds like a phenomenology of the invisible: a time that is both frozen and swift, a sound universe of the small and the tenuous, with sometimes tiny sonorities, microscopic rhythmic madness (beats as light as those of insect wings), sounds with intense and contained energy, sparkling layers. Its division into seventeen separate movements (some of which are linked) gives the sensation of a constantly renewed labour, rather than that of a flat duration. Jeîta also corresponds, chronologically, to the arrival in the GRM studios of the first synthesizers, which allowed the composer the high-pitched frames and glittering textures that are one of the “trademarks” of his sound.