Early ElectroMIX is a series to document the history of experimental Electronic music from the 50s to the 80s, composers making use of electronic instruments, test equipment, generators of synthetic signals and sounds, tape manipulations… to analog synthesizers…

While our sessions document those who make it today my desire is to transmit some pioneering works which paved the way to what we try to create.

Our 50th entry in the series has to be special and I can’t think of anything better than to bring together music dedicated to those « Ladies with transistors ».

It is actually a mix I had completed for Dublab radio in 2022 and it’s high time to give it visibility via our platform and draw attention to the fact that for decades, the historiography of electroacoustic music had been written from a narrow perspective — centered on a handful of European and North American men: Schaeffer, Henry, Stockhausen, Bayle, Maderna, Berio, and later, Parmegiani or Ferrari. The prevailing narrative often treated this history as a linear progression of technical innovation, driven by male “inventors” of sound technology, with women portrayed as assistants, performers, or anomalies.

In reality, the studios of the 1950s and 1960s — from the GRM in Paris to the WDR in Cologne — included many women composers whose creative agency was obscured by institutional hierarchies and publication practices. Works that you will hear in this mix directly challenge this imbalance.

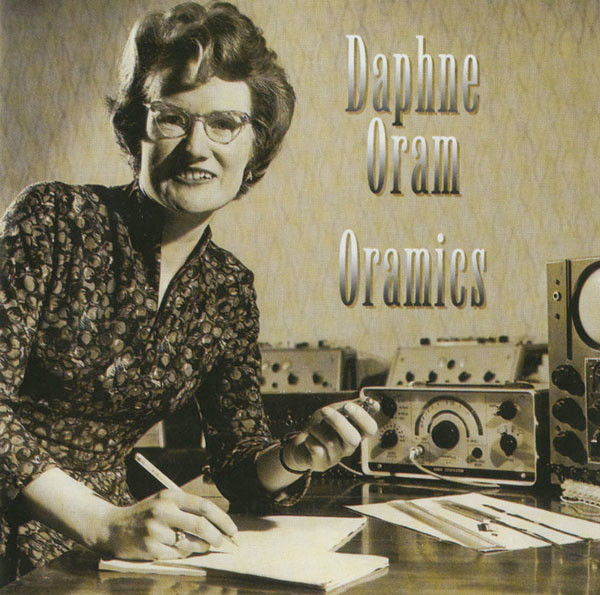

In Latin America, Jocy de Oliveira merged electronics, voice, and performance in visionary multimedia works (Estória, Solitude Trilogy), bridging the personal and the technological. From Argentina Beatriz Ferreyra’s work belongs to a larger constellation of women who, often independently and against institutional invisibility, reshaped the possibilities of electronic sound across continents. Daphné Oram in Britain, co-founder of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, built her own Oramics machine to literally draw sounds, reclaiming authorship through invention. In North America, Pauline Oliveros redefined listening itself through her Deep Listening practice, framing technology as an extension of perception and empathy. Daria Semegen, working in U.S. academic studios, forged intricate, polyphonic tape compositions (Electronic Composition No. 1) that rivaled the structural complexity of her male contemporaries, yet were rarely canonized.

In Canada, Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux pushed the boundaries of electroacoustic theatre and spatial sound, while in the U.S., Alice Shields explored the expressive and ritual potential of electronic voice transformation — anticipating today’s discussions of posthuman and cyborg identities.

Across their differences, these composers share a radical re-imagining of what electronic music could mean: a space for affect, embodiment, and multiplicity, not merely the demonstration of technical power. Their practices foreground intuition, listening, and transformation — qualities long devalued within a masculinized discourse of control and system. Seen together, they reveal that the history of electroacoustic music is not a single European lineage but a global network of voices: poetic, experimental, and defiantly diverse.

The Electric Constellation: Women Who Dreamt in Voltage

There was a time before the click, before the spark — when silence still dreamed of its own electricity.

From that dreaming rose eight figures, magnetic and luminous, each carrying the hum of a new world.

They were not saints, nor engineers — but priestesses of resonance, summoning thunder from wire and voice, breath and tape, ghost and gesture.

They did not compose; they conversed with the invisible.

Tracklist:

Jocy de Oliveira – Estória (1981 / Fif) 00:00 > 00 > 11:25

Beatriz Ferreyra – Demeures aquatiques (1967 / Sub Rosa) 11:13 > 17:30

Daria Semegen – Electronic Composition No. 1 (1972 / Columbia) 17:09 > 22:55

Pauline Oliveros – Alien Bog (1967 / Pogus) 22:07 > 37:23

Alice Shields – Dance Piece No.3 (1970 / New World) 36:17 > 40:53

Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux – Trakadie (1970 / RCI) 40:50 > 51:45

Delia Derbyshire – Pot-au-feu (1968/BBC Radio Enterprises) 51:20 > 54:31

Daphné Oram – Episode Metallic (1964/Paradigm) 54:26 > 58:53

Eight names, eight frequencies — a chorus vibrating across decades and continents.

Their works defied the sterile myth of technological progress.

They redefined what it meant to compose: to listen, to transform, to be.

Their legacy is not nostalgia but ignition.

They taught us that electricity can feel, that structure can breathe.

As the world hums with new machines, their signal persists — faint but indelible.

In every drone, every glitch, every shimmer of feedback,

You can still hear them — the women who dreamt in voltage…

Philippe Petit / November 2025.

Jocy de Oliveira – Estória (1981 / Fif)

« Estórias Para Voz, Instrumentos Acústicos e Eletrônicos » is not merely a composition — it is an oracle, a pulse, a classic of the Brazilian electronic scene of the 1970s that sounds so fresh to my ears…

It speaks of a woman who dared to sculpt sound into myth, of a Brazil where the air itself seemed to vibrate with electricity and memory.

Born among tropical resonances, Jocy de Oliveira began at the piano — that obedient beast of tempered harmony — only to make it roar and dissolve into pure sound.

Jocy De Oliveira began her career as a concert pianist, who fled early, crossing oceans to America and Europe, not to escape but to expand — to stretch the boundaries of listening and focus on avant-garde works. She studied in America and Europe, before being recruited by major orchestras on both continents, and Stravinsky himself wrote under the spell of her playing. She became the first to summon the wild architectures of Berio, Xenakis, Santoro, Cage, Manuel Enríquez — her fingers translating their impossible geometries into breath. Her performance of Messiaen’s Catalogue d’Oiseaux is still widely regarded as the definitive version: birds transmuted into pianistic flight, feathers turned to flame.

But somewhere in the 1960s, Jocy turned away from the keys and toward the invisible. She began to compose with wind, voice, tape, and silence — gathering the world’s murmurs into an ever-shifting theatre of sound. Her music no longer wished to be “performed” — it wished to live.

She folded organized sound into every possible space: public squares and private rituals, installations and film, dreams and the electromagnetic ether.

Performance became composition; composition, performance, and sound escaped its cage to dance with light, movement, and memory.

“Estórias” — the plural of story — is the living proof of that metamorphosis: an opera of the self and the cosmos, a tropical electronic prayer where myth and circuitry intertwine. Listening to it today, I still feel its voltage: bright, dangerous, tender. A tale told not with words, but with frequencies.

« Estórias Para Voz, Instrumentos Acústicos e Eletrônicos » was released during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964-1985) and thus carries implicit resistance and cultural significance: it is described as “an eclectic and inventive record … one of the most important cultural artifacts of 20th-century Brazil”.

The album brings together voice, acoustic instruments and electronics in a way that blends tradition and avant-garde, Brazilian musical heritage and global experimental techniques. It thereby opened up new possibilities within Latin American and women-composer histories of electroacoustic/multimedia music.

Structurally and philosophically, Estórias is a living organism — part ritual, part circuitry.

It reflects de Oliveira’s commitment to interdisciplinarity and breathes through many mouths: music, theatre, video, installation — each one a portal into another dimension of perception which dissolves the borders between forms as if melting metal with her gaze: sound becomes image, movement becomes pulse, language becomes vibration.

Her experimentation with voice and electronics travels through cables and air alike, half human, half spectral, whispering both to Brazil’s red earth and to the satellites circling above it, as a challenge to boundaries between art forms and between the local (Brazil) and the global that are not opposites but mirrors — the jungle and the machine dreaming each other into being.

The materials include voice, acoustic instruments (prepared piano, violin, percussion, synthesizers, electric celesta) and electronics/tape. The voice is used not always for text but often for vocalizations, extended techniques, and amalgamated with electronics. The piece draws on influences from diverse traditions: Brazilian percussion and immigrant community sounds, Indian raga, Japanese Shōmyō chanting (monastic vocal tradition) — all integrated into the mix. Such integration of voice/acoustic/electronic elements into a single coherent work (not simply “voice + electronics” BUT deep integration) was relatively unusual at the time, especially in Latin America and here the voice is treated as a sound-object: the text uses word-play, Portuguese, Sanskrit, Japanese phonetics (e.g., “Era uma vez uma memória” / “Uma mahẽs vara …” / “shomyo” / “náda” / “nada”) to create a sonic/rhetorical field rather than a straightforward narrative. The piece engages multimedia logic — the voice and instruments on one side, the electronics/tape on the other — as a field of interaction rather than hierarchy. The form is open, slips and shimmers — half improvised, half carved in secret stone. It flirts with accident, dances with air, and lets the world leak into its circuits: birds, laughter, echoes, maybe even ghosts. Nothing here stays still — it breathes, it blinks, it forgets itself and starts again. Once lost in time, the album has been reissued and is recognized as essential in the history of experimental music. It helps expand the canon beyond the usual Anglo-European centres.

Now that Estórias has resurfaced, revived — it no longer belongs to its time.

It floats above decades, still warm, still dangerous, still whispering secrets in a language that is half human, half storm.

This is music that remembers the future. A tropical séance. Somewhere between the pulse of a jungle and the hum of an oscillator, Jocy de Oliveira conjured a new species of sound where tropical humidity met starlit machinery — half goddess, half transistor she gave to us a fever dream carved into magnetic tape.

In Estórias, the voice is not sung, it blooms: whispers become wings, sighs become thunder, vowels melt into luminous frequencies.

Every phrase sweats. Every silence glows.

Electronics ripple like the surface of a river under moonlight, and the acoustic instruments answer — reeds, strings, drums — like ancestral spirits seduced by voltage.

It is Brazil, yes, but not the Brazil of postcards.

It is a dream-Brazil — mythic, fevered, underwater — where language dissolves into vapor and the body becomes an antenna for desire.

The music moves like a ritual both ancient and futuristic: improvisation rubbing against structure, chaos embracing form, sensuality leaking into circuitry.

And she is still here.

At more than eighty years old, Jocy de Oliveira continues to compose — not from nostalgia, but from necessity, as if sound were the breath that keeps her alive. Her music still vibrates with the same luminous fever, the same hunger to merge body, acoustics, technology, and myth. Time has not tamed her — it listens to her.

Feel free to come listen to this marvelous work she contributed to Modulisme:

https://modulisme.bandcamp.com/track/jocy-de-oliveira-nherana

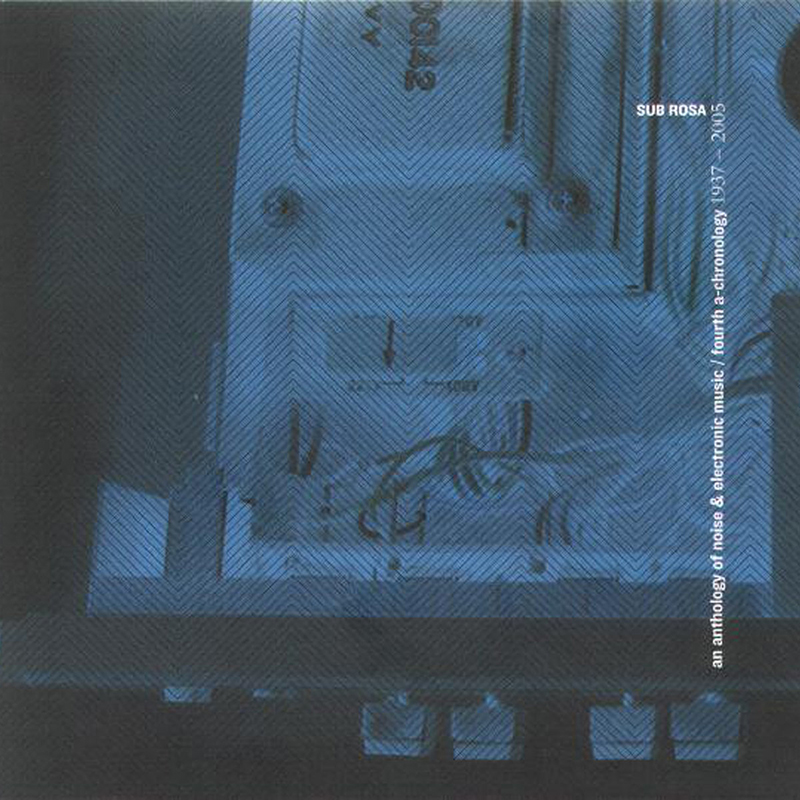

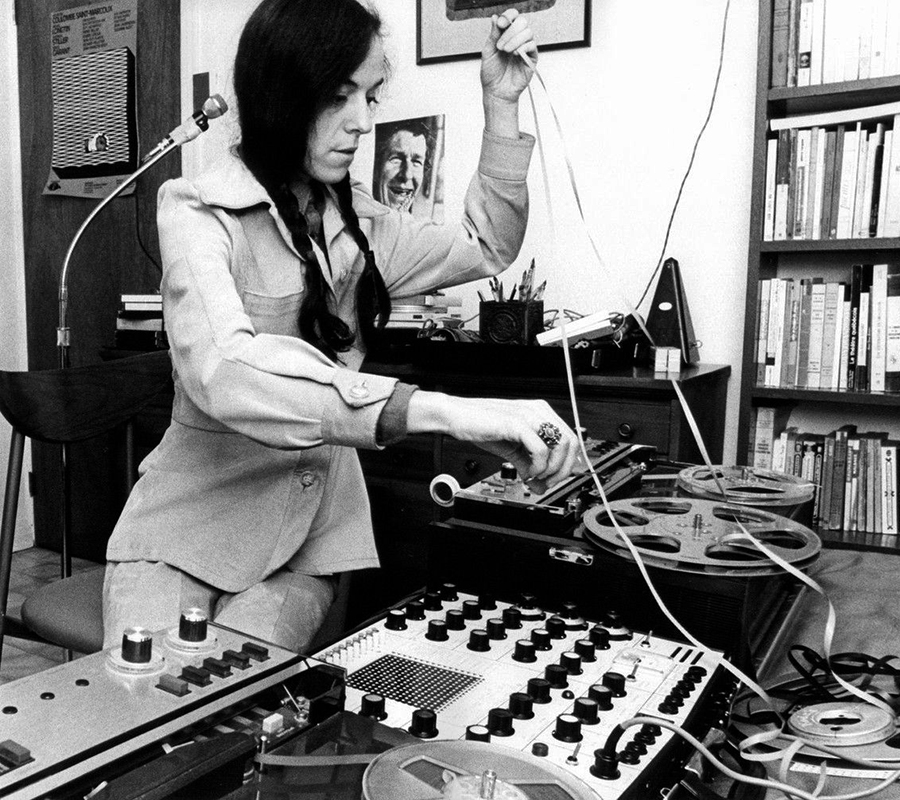

Beatriz Ferreyra – Demeures aquatiques (1967 / Sub Rosa)

Argentine-born, Paris-brewed, Beatriz Ferreyra arrived at the Groupe De Recherches Musicales (GRM) like a drop of warm rain in a room full of machines. She studied with the great Nadia Boulanger, yes — but she soon preferred the whisper of oscillators to the discipline of harmony. From 1963 to 1970, she haunted the corridors of Schaeffer’s temple of sound, helping him (with Guy Reibel) give birth to Solfège de l’objet sonore — the alphabet of modern listening.

Somewhere between the hum of tape reels and the glow of coffee cups, she composed « Demeures aquatiques » — a piece that doesn’t sit still, it ripples.

Ferreyra worked at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) alongside Schaeffer and Bayle, contributing not as a technician but as a full composer — yet her name rarely appeared in the canonical textbooks. She didn’t “assist”; she was a full composer swimming upstream through a male, Eurocentric current that often pretended not to see her.

While others built sonic cathedrals, she built rivers. Her music flows, listens, evaporates. It doesn’t conquer technology — it seduces it, and embodies precisely what the male-dominated historiography tended to marginalize: a poetics of listening, fluid material transformations, and a refusal of the technological bravura often celebrated in her male contemporaries. Rather than pursuing the monumental, system-driven structures that characterized much post-serial electronic music, Ferreyra’s approach is organic, phenomenological, and sensuous. She reclaims the studio not as a laboratory of control but as a space of dialogue — between solid and fluid, body and sound, matter and perception. The studio became her lagoon — a place where solid and liquid, human and electronic, merged in slow motion.

Since 1970 she has continued to compose freely, fearlessly — her later albums for Room40 and Persistence of Sound still glowing with the same quiet fire.

Beatriz Ferreyra, now in her nineties, remains the wild ear of electroacoustic music — listening where others measure, dreaming where others document.

« Demeures aquatiques » uses as sound sources classical and unorthodox instruments — metal sheets, glass rods, etc., invented by the Baschet brothers. The metal/glass objects’ resonance gives a metallic, shimmering timbre; when processed (filtered, slowed, layered) these materials evoke watery, fluid spaces, or subterranean resonances. Such choice of sources (metal sheets, glass rods) and her treatment of them show an early suggestion that non-instrumental timbres, when processed, can become musical forms. In Ferreyra’s hands they cease to be objects and become beings. Each vibration a pulse, each resonance a secret body trembling in space.

From these humble, unruly sources she forges a new kind of music — not played, but summoned. Sound itself becomes flesh, architecture, atmosphere.

Here begins the revolution: where noise dreams of melody, where texture becomes form, where the world itself — its echoes, its surfaces, its breath — enters the score. These first alchemical gestures opened doors for later electroacoustic and sound-art explorations of texture, space, environment : sound as matter, matter as music, the environment as an instrument of wonder.

The title “aquatic mansions” suggests immersive enveloping spaces. Texture shifts: from sparse shimmering layers to denser clusters, from object-resonances to ambient fields. The transition from “solid to fluid” can be heard as the sound becomes less defined, more dissolving, more ambient. The listener may perceive sound moving, overlapping, folding inwards; the piece invites attention to sound as environment. The conceptual underpinning (solid/fluid, object/process) gives the work a coherence and depth: sound is not just material, but metaphorical — exploring states of matter, transitions, the interplay of form and dissolution.

Ferreyra herself describes the piece: “The flow is constantly facing the ebb. … I wanted to illustrate the perpetual attempt by the solid and the fluid to interpenetrate via this experimental approach through earth, sea and air: overlapping elements folding inwards, bursting as tiny particles toward soft and flat surfaces.”

Indeed the elements do not merely coexist — they collide, melt, and reassemble in slow delirium. Earth murmurs underwater; air folds like silk around the metallic pulse of light. The solid and the fluid wrestle and caress each other in perpetual metamorphosis, a dance of friction and tenderness.

What she describes is not just a compositional idea — it is a cosmology. The piece becomes a living landscape where gravity dissolves, where sound behaves like weather, like blood, like memory. It is as if Ferreyra had taken the raw matter of the world — stones, waves, vapour — and invited them to dream inside a magnetic tape. It is a music that trembles, that remembers the sea inside every solid thing. A surreal communion between physics and poetry — and a timeless act of resistance against rigidity.

Thus, the piece emerges in the mid-1960s, at a pivotal moment for electroacoustic music in Paris, with Ferreyra bringing an individual voice into a predominantly male-dominated field. Her work at GRM, helps mark the evolution of studio composition from object-based sound research to more textural, phenomenological soundworlds.

The piece structure is in “two clearly distinct parts” (according to the liner notes):

The first part might introduce the “sounding object” repeating, perhaps giving a sense of “fixity” (as Ferreyra notes) and then the second part transforms that object, dissolving it into something more fluid, more mobile.

The listener is guided through contrast: repetition → transformation, the “object” of sound that seems fixed becomes mobile, the fluid becomes structured. Temporal perception plays a central role: because the piece evolves via tape-manipulation, filters, overlapping layers, the form is defined by trajectory and change—not by melody or rhythm in a traditional sense.

Back in 1967 this major work undermined both the gender hierarchy (by asserting a distinctly feminine and intuitive mode of composition) and the geopolitical hierarchy (by inserting a Latin American voice into a European institutional field). The piece thus participated in a broader rewriting of electronic music history — one that restored the visibility of women and non-European composers not as exceptions but as essential agents in the evolution of sonic thought.

In this light, « Demeures aquatiques » is not merely an aesthetic achievement; it is a political and epistemological act. It reminds us that the sound studio, so often mythologized as a site of male genius and technological power, can also be a space of care, fluidity, and embodied listening — qualities that Ferreyra’s work brings to the foreground of electroacoustic art.

A composition which stands today as an anthology piece not for its perfection, but for its mystery.

It refuses monumentality; it breathes instead.

Each texture is alive, each shimmer a heartbeat.

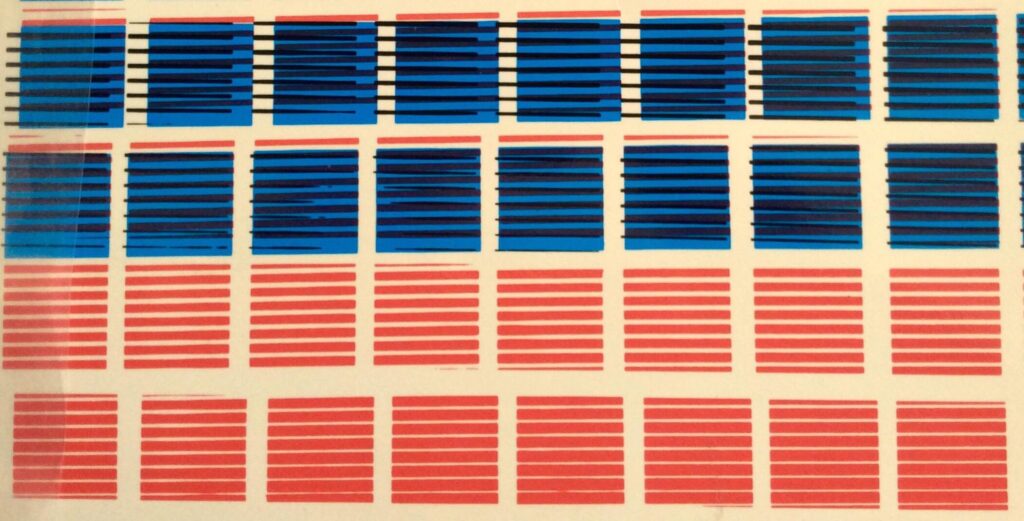

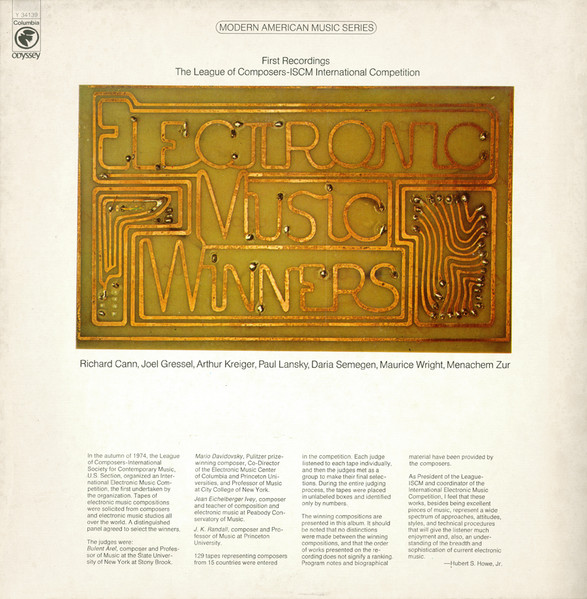

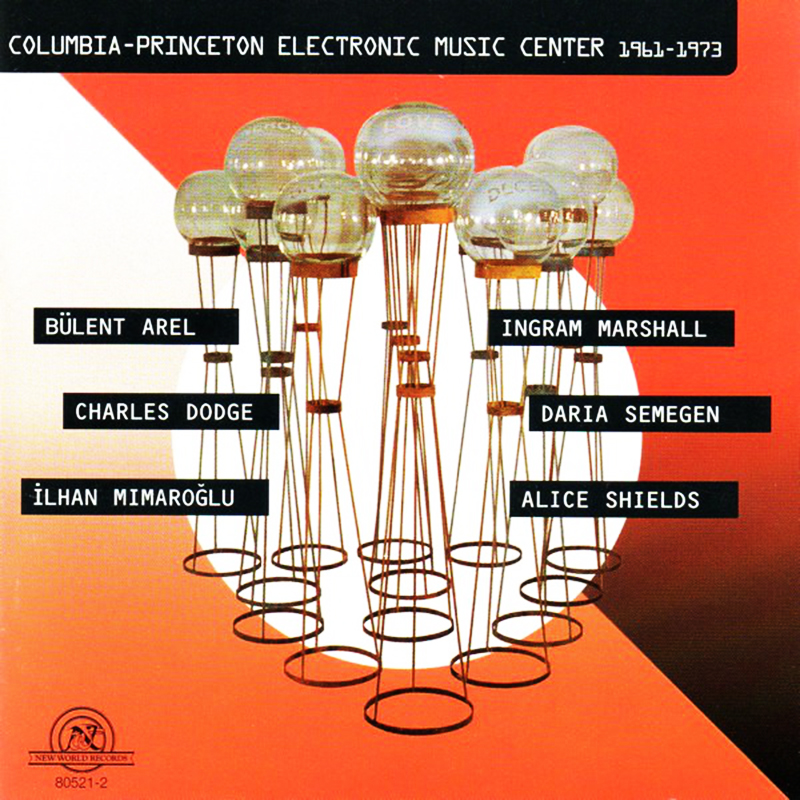

Daria Semegen – Electronic Composition No. 1 (1974 / Columbia Odyssey)

Daria Semegen is a contemporary American composer of classical and electroacoustic music who studied composition with Bülent Arel and Alexander Goehr and later taught at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center between 1971 and 1975. One of the leading figures of the “second generation” of American electroacoustic composers affiliated with the State University of New York at Stony Brook, she represents a moment when American tape music was transitioning from experimental laboratory research toward mature compositional languages.

She is a figure on the academic side, linked to the conservatory and the university, and her writings cover a wide range of topics related to music composition and have been studied by other scholars.

She is currently Associate Professor of Composition, Theory and Electronic Music Composition at Stony Brook University, where she directs the Electronic Music Studio.

Composed in 1971 at the Columbia–Princeton Electronic Music Center, Electronic Composition No. 1 belongs to a period when the center’s resources — sine-tone generators, filters, reverb chambers, splicing blocks, and multi-track recorders — enabled a high degree of precision in sound design. While many contemporaries were moving toward modular synthesizers or live electronics, Semegen continued the meticulous, hands-on tape-composition method, emphasizing formal rigor and timbral detail.

At a time when female composers in academic studios were often marginalized in the sterile glow of the early academic studios — where cables coiled like sleeping serpents and the hum of machines replaced the murmur of rivers — Daria Semegen dared to sculpt thunderstorms. « Electronic Composition No. 1 » asserted a distinct voice: neither minimalist nor romantic, but intensely architectural and sculptural in its treatment of sound. It’s a terrain of forces. Sparks, fractures, and magnetic sighs — a music that builds cathedrals out of electrons and then melts them under its own fever.

At a time when women’s voices were confined to the margins of the console, Semegen seized the tape and turned it into architecture — not of stone, but of pulse and lightning, demonstrating how pure tape composition — splicing, filtering, layering — can yield formal clarity comparable to instrumental music. Each splice is a heartbeat cut open; each filter, a gust of cosmic wind. The piece unfolds like a living organism, layering-breathing in bursts and silences, carving time itself into luminous strata.

The opening ignites — sharp flashes, microscopic explosions… bursts of percussive, granular material — quick, sharply cut sounds that define a kinetic space.

Then the air thickens: evolving clusters and glissandi, often achieved by tape manipulation and varispeed techniques, suggesting motion and spectral expansion, spectral tides slide and shimmer, bending under invisible gravity.

Finally, everything disintegrates — a return to silence and sparse punctuation leaving only suspended dust, echoes, a hush charged with aftermath.

The result is a polyphonic form of electroacoustic writing — gestures overlap, answer one another, and form large-scale dialogues rather than a single linear evolution.

This is not minimalism, not romanticism — it’s tectonic music, restless and untamed.

Semegen doesn’t “compose” sound; she liberates it, lets it find its own geometry, its own tremor, her art stands like a secret monument to feminine audacity — a storm carved into tape, still crackling fifty years later.

Out of the magnetic night of the tape machine, Daria Semegen summoned voices that no longer remembered their origin. sources include both synthetic tones and concrete sounds: metal sighs, spectral vowels, phantom percussion — everything melted, recomposed, reborn. Her sounds are not “sources” but creatures, spectral morphologies unfolding like slow flames. Each tone carries its own skeleton, its own shadow, its own secret erosion.

The contrasts between impulsive events (short, percussive gestures) and continuous spectra (gliding or modulated tones) create tension between pointillism and continuity — a hallmark of her style. Her control of stereo perspective and timbral depth + texture reveals a sensitivity closer to instrumental orchestration than to algorithmic or process-based sound design. Each layer is placed with compositional precision; silence and resonance are integral structural elements. She focuses on spectral morphology: the inner structure of each sound — its attack, resonance, decay — becomes the basis for large-scale form. Time is sculpted from contrast: flashes and flows, impulses and fogs. Sharp detonations pierce the ether, then dissolve into long, liquid tones that slide across the stereo field like the movement of planets. The ear drifts between two magnetic poles — one made of sparks, the other of breath.

Semegen orchestrates these ghosts with the precision of a symphonist and the delirium of a dreamer. Silence is not absence, but inhalation; resonance is not decay, but a shimmer of memory.

She does not build utopias of technology nor meditate in minimalist stillness — she weaves a grammar of friction, a counterpoint of textures that breathe and collide.

Semegen’s music resists the poles of either the European “technological utopia” (Stockhausen, Koenig) or the American minimalist/post-Cagean stream. Instead, it develops a personal syntax of timbral counterpoint — a structural, gestural, and expressive language grounded in studio craft. Her studio is a theatre of metamorphosis. Sounds arrive as matter, and leave as spirit.

She once said that composing electronically was “sculpting sound in time” — and indeed, in « Electronic Composition No. 1 » , time itself bends beneath her hands like molten metal. Form does not exist in advance; it rises from the breath of the material, from the invisible architecture of vibration. Each sound seems to remember the moment it was born — scraped from silence, shaped by fire, and released into air.

This piece is both a technical tour de force and a philosophical statement: an affirmation that electronic music can embody structural thought, emotional nuance, and material exploration simultaneously. Not just a technical feat — it is a manifesto whispered through magnetic tape, a declaration that emotion and intellect, intuition and structure, pulse together in the circuitry of the studio. Within the history of electroacoustic music, it corrects the imbalance of visibility and demonstrates that the tradition of compositional rigor was never the exclusive territory of men or of Europe. Through her alchemy, the machine ceases to be a cold apparatus: it becomes a creature that listens, hesitates, dreams.

In Semegen’s hands, the studio transforms into an instrument of vision, where sparks and silences converse, and music breathes with a rare intelligence — lucid and feverish all at once. To hear this work is to feel sound carve the air around you, to sense a woman sculpting the invisible.

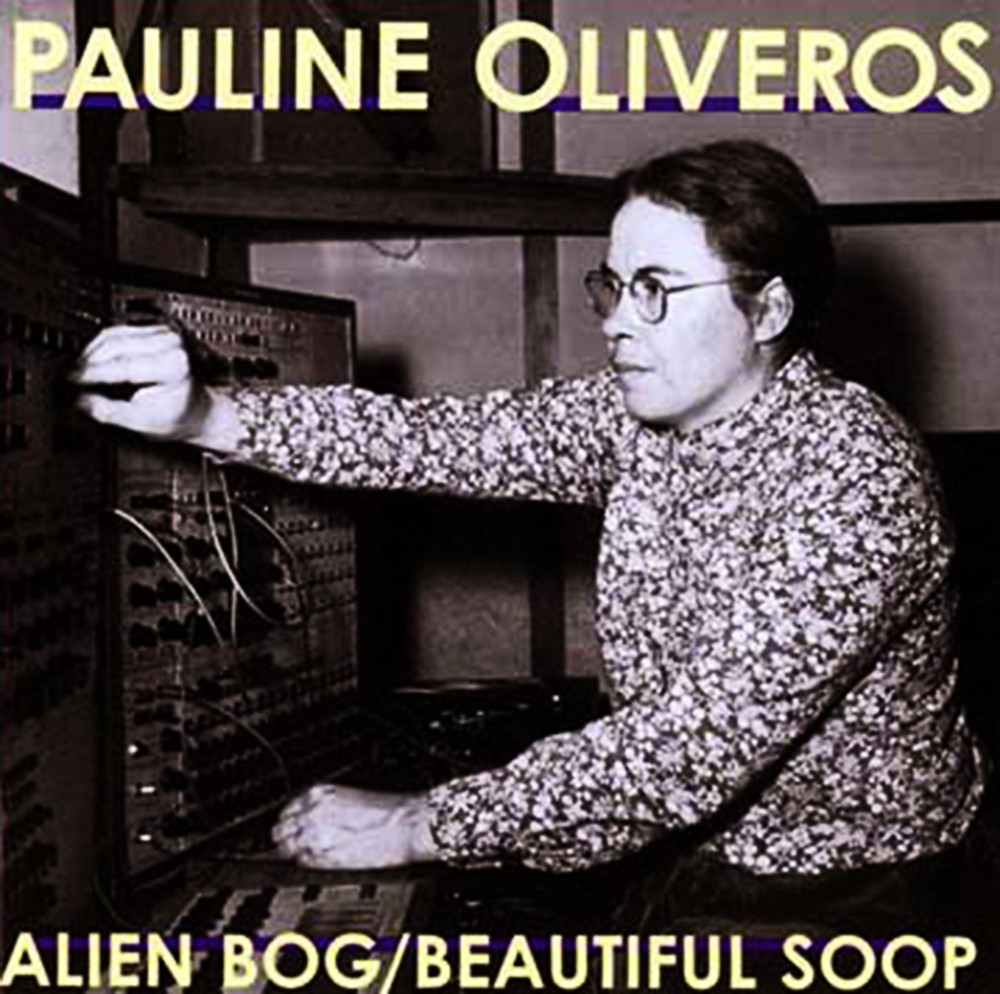

Pauline Oliveros – Alien Bog (1967 / Pogus)

Long before the serene depths of Deep Listening, there was a wilder Pauline — the one who dove headfirst into the circuitry, laughing with electricity. In the humid nights of San Francisco, amid cables and magnetic reels, she and her comrades Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender gave birth to the Tape Music Center — a temple of sound and light, half-laboratory, half-dream. There, she met the newborn Buchla Box 100, a shimmering creature built by Don Buchla, a machine that didn’t just produce tones but hallucinations. « Alien Bog » is her second piece playing that original analog synthesizer of exception, and from its glowing body emerged a composition crawling with mysterious life, amphibious voices, cosmic frogs singing in frequencies unknown. It’s a piece that hums like the edge of a dream, a meeting of woman and voltage, breath and circuit. Beneath the surface, you can already hear the pulse of what she would later call Deep Listening — that vast underwater consciousness where sound and being dissolve into one another.

Before she taught us to listen deeply, she made the machines speak in tongues.

During the mid-1960s, Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) was a central figure in the San Francisco Tape Music Center, one of the most important hubs of American experimental music alongside the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center.

Founded in 1961 by Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, and Ramon Sender, the SFTMC was a community-based studio dedicated to open experimentation rather than institutional research. Its environment—equal parts collective and laboratory—allowed composers to engage directly with the new electronic technologies emerging in California’s countercultural context.

It was at this center that Don Buchla designed the Buchla 100 modular synthesizer (commissioned by Subotnick and Sender in 1963), a radically new interface for sound creation. Unlike the Moog, which imitated keyboard instruments, the Buchla was non-tonal and spatially oriented, suited to experimental improvisation. Oliveros quickly became one of its most imaginative users, treating it as an expressive organism rather than a machine, and consequently she helped define the West Coast synthesis aesthetic focused on voltage control, improvisation, and sonic behavior rather than pitch sequencing.

Composed in 1967, Alien Bog is one of her first works entirely realized on the Buchla synthesizer and tape. It was created at night in a studio that looked out on a pond behind Mills College — whose frogs and insects inspired the title and the sound world of the piece.“I was deeply impressed by the sounds coming from the frog pond outside Mills’ studio window. I loved the accompaniment as I worked on my songs. Although I never recorded the frogs, I was of course influenced by their music.”

« Alien Bog » is not a composition — it’s a breathing swamp of electricity which conjures an uncanny ecosystem of synthetic “creatures”. A world where machines croak, shimmer, and exhale. From the depths rise synthetic creatures: metallic frogs, phosphorescent insects, invisible birds whose wings are made of voltage. Croaks become constellations; bubbles burst into galaxies. Every sound wriggles with uncanny life.

The sonic materials are organized as clusters of gestures rather than fixed pitches or rhythms — sequences of attack-decay envelopes, evolving feedback tones, and modulated bursts. Oliveros, half-scientist, half-sorceress, bends her oscillators and filters until they pulse like living cells. Her tape delay stretches time itself, turning each gesture into an echo of something primordial — not imitation of nature, but a new nature altogether, one born of signal and breath.

The piece doesn’t begin or end — it germinates, blossoms, evaporates. A soft pulse becomes a storm of frequencies; the swamp swells with alien voices, then retreats again into stillness. You don’t just listen to Alien Bog — you sink into it, waist-deep in its luminous mud.

When the final echoes fade, it feels less like silence than the memory of a world that continues to hum somewhere, just below the skin of the earth.

The lack of metric regularity and the non-repetition of motifs emphasize a natural temporal flow—time as ecology, not as structure while managed to create spatial illusion: sounds appear to move closer or farther away, circling the listener. This spatial dynamism is integral to the piece’s drama. Oliveros often described her process as “composing by listening,” letting the behavior of circuits guide musical decisions. The synthesizer is not a tool of control but a collaborator — an instrument that “listens back.” which marks a decisive departure from the algorithmic control typical of academic studios in Europe.

« Alien Bog » is a cornerstone of 1960s electronic music — technically innovative, structurally organic, and philosophically radical. It redefined what a synthesizer composition could be: not a display of machinery, but a meditation on listening, ecology, and the porous boundary between human and non-human sound.

Its influence extends far beyond its ten-minute duration — shaping the aesthetics of immersive, environmental electronic music for generations to come.

Alice Shields – Dance Piece No.3 (1970 / New World)

Alice Shields lives where sound dreams of becoming flesh. Composer, singer, alchemist of breath and voltage — she walks the electric frontier between ritual and circuitry. Once Associate Director of the fabled Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, she shaped the invisible architecture of American electronic sound, weaving logic and delirium through magnetic tape.

But Shields is never just a technician. She is a voice — trained in opera, tempered by myth — who lets her lungs speak through oscillators, who sings with the machines until they tremble like living creatures. Her music listens inwardly, where the psyche hums; she teaches not only the psychology of music but the secret art of letting frequencies feel.

In recent years, her imagination has wandered eastward — into the disciplined mystery of Indian classical music, into the moonlit masks of Noh theatre. There, she finds the same pulse she once sought in the studio: the breath that binds the human to the spectral, the performer to the echo.

At more than seventy years of age, she continues to compose — still restless, still radiant — a priestess of thresholds, forever tuning the air between worlds.

Alice Shields’s « Dance Piece No. 3 » (1970) is a striking example of how early American electroacoustic composers began merging technology, movement, and ritual. It’s both a musical composition and a choreographic structure, embodying Shields’s dual identity as composer and trained opera singer-dancer. If Oliveros communed with the swamp of sound — breathing through her Buchla like a creature of light and mud — then Alice Shields danced in the cathedral of voltage. Her world was not a bog but a stage: choreographed frequencies, bodies turning in magnetic air. Where the Buchla composers surrendered to the pulse of electricity, Shields sculpted it into gesture — she gave the current a spine, a heartbeat, a dancer’s trembling foot. « Dance Piece No. 3 » is one of the earliest electroacoustic works composed explicitly for dance performance, predating the widespread “interactive” electronic-dance collaborations of later decades. Conceptually, it bridged the modernist studio with the ritual and expressive dimensions of performance, aligning with contemporaries like Pauline Oliveros (Alien Bog, I of IV) and Beatriz Ferreyra (Demeures aquatiques).

Alice Shields was among the very few women to work extensively at the Columbia–Princeton Electronic Music Center (CPEMC) in New York during the 1960s–70s — a space dominated by male figures like Vladimir Ussachevsky, Otto Luening, and Milton Babbitt. By the late 1960s, the CPEMC had become a crucible for tape and synthesizer composition in the United States, paralleling European institutions such as the GRM in Paris or WDR in Cologne. But unlike many of her male colleagues, Shields was not content to treat electronics as purely abstract or serial tools — she wanted to connect electronic sound to the body.

Indeed Alice Shields did not want to trap electricity in cold equations. She wanted it to breathe. To tremble like skin, to arch like a spine awakening from dream.

Out of this hunger came « Dance Piece No. 3 » — not a mere tape composition, but a ritual of motion and voltage, a duet between the dancer’s flesh and the machine’s invisible pulse. Composed specifically for dance performance, exploring how the taped electronic soundscape could shape and respond to movement. The piece thus stands at the crossroads of electroacoustic music, dance theatre, and embodied performance — a rarity in its time.

The work is a fixed-tape composition using analog electronic sounds, later diffused in performance spaces as accompaniment for live dancers. Shields used sine-wave oscillators, noise generators, tape splicing, and filtering to produce a vocabulary of synthetic gestures — percussive bursts, gliding tones, and dynamic envelopes that suggest kinetic motion. These sounds were not random; they were composed to embody the dancer’s energy, matching phases of tension, release, and transformation, she sculpted sound as if shaping muscles out of air — sine waves stretching, contracting, exhaling. Noise became breath, glissandi became gesture. Each burst of sound seemed to pirouette; each silence felt like the poised stillness before the leap. The tape did not accompany the dance — it was the dance, its echo, its secret double.

The absence of metric rhythm gives way to organic pacing, aligning sonic texture with the dancer’s internal pulse rather than external beat — a hallmark of Shields’s sensitivity to embodied time. The sound world is sculptural rather than harmonic. Each gesture functions as an “acoustic movement” — a sonic analogue to the dancer’s motion. Indeed there is no rhythm here, only heartbeat and suspension, no meter but the body’s own tide. The sounds sway, collide, shimmer, like dancers lost in a slow trance of light and voltage. Shields listens to the body’s electricity and translates it into sound: sinews of tone, nervous sparks of resonance.

« Dance Piece No. 3 » brings the human body back into the center of electronic composition. Shields refuses the idea that tape music must be acousmatic (heard without visible source). Instead, she integrates the live body and recorded sound into a shared expressive field, she reclaims the machine from abstraction — it no longer computes, it feels. The tape is no longer a ghostly presence behind curtains but a living partner onstage, sweating, breathing, answering.

Through her, electronics remember the body — and the body remembers it was always electric.

This anticipates later developments in electroacoustic theatre and mixed media performance, such as those by Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux.

Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux – Trakadie (1970/Radio Canada International)

Born on August 9, 1938, in the remote forests of La Sarre, Québec, and gone too soon on February 2, 1985, Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux was one of the boldest Canadian voices to emerge from the era when electricity first began to sing. She studied at the Conservatoire de musique du Québec à Montréal, where she earned top prizes in composition, harmony, counterpoint, and fugue.

A scholarship from the French government led her to Paris in the late 1960s, where she worked under the influence of Iannis Xenakis, who encouraged her to explore the experimental laboratories of sound. In 1968, at the suggestion of Iannis Xenakis, she went to Paris to familiarise herself with the ORTF’s Groupe de recherche musicale, not as a student, but as a conspirator of sound, and there – among the magnetic coils and spectral whispers – she worked with François Bayle, Guy Reibel and Bernard Parmegiani.

She learned to bend electricity like breath, to let frequencies shimmer like fever dreams. In 1969, with five kindred spirits she founded the Groupe International de Musique Électroacoustique de Paris (GIMEP), a travelling comet of sound that streaked across Europe, South America, and Canada between 1969 and 1973. For Saint-Marcoux, this was not merely research — it was a kind of ritual theatre of sound, a search for the secret life within vibrations. Her work from this period reveals a fascination with motion, density, and the poetic transformation of matter — how a single resonance can open like a flower or explode like a star.

Returning to Montréal in 1971, she became a central figure in Canada’s contemporary music scene.

She taught composition and electroacoustic music at the Montréal Conservatory, inspiring a generation of composers to treat the studio not as a machine room but as a sanctuary for the imagination, her suitcase was full of ghosts, tapes, and winds from every continent. She began to teach, yes — but more than that, she began to ignite. At the Montréal Conservatory, she sculpted sonic rituals, teaching her students that sound is never neutral, that every vibration has a pulse and a secret.

in addition to teaching at the Montreal Conservatory, she became fully involved in the Quebec and Canadian music scene by composing a succession of works for small ensembles, or commissions for large Canadian orchestras, compositions with strange titles, evocative of the climates she created, such as « Trakadie ».

Saint-Marcoux’s electroacoustic writing defied categories. Her sound worlds are simultaneously earthbound and cosmic, oscillating between discipline and instinct, architecture and dream. She sought the point where gesture becomes matter — where sound ceases to represent and instead becomes.

Her music often feels like a dialogue between the elements: air and metal, fire and breath, control and eruption. Listening to « Trakadie » one may enter a landscape where electricity hums like a memory, where the voice of Québec’s wilderness meets the restless architecture of sound.

« Trakadie » is one of the most striking examples of early Canadian electroacoustic theatre: a dense, dramatic composition that fuses tape music, human gesture, and the poetics of spatial sound. It sits at the intersection of musique concrète, live performance, and conceptual ritual. It is not “music” in the traditional sense but sound theatre: a dramaturgy built entirely from acoustic gesture. The piece unfolds like a ritual enacted by sound alone. This anticipates later electroacoustic theatre by Francis Dhomont and Robert Normandeau, who both cited Saint-Marcoux as a major influence.

The title refers to Tracadie Bay in New Brunswick (from the Mi’kmaq word Trakate, “camping place”) — a region rich in Acadian cultural and linguistic history. The word evokes both a place and an echo of displacement: memory, migration, and loss. The piece thus situates itself at the meeting point of territory, identity, and sonic ritual.

A tape composition, built from concrete and electronically transformed sounds. Sources likely include human voice fragments, metallic resonances, wind, percussive strikes, and processed natural ambiences — all carefully layered through tape manipulation (filtering, speed variation, splicing, and reverb). Saint-Marcoux approaches sound not as melody or harmony but as energy in motion. Each gesture — an impact, a breath, a resonance — functions like a “stroke” in a choreography of sonic matter. The piece unfolds in contrasting sonic tableaux, alternating between tension and suspension:

• Emergence: isolated percussive attacks punctuate silence — “points of energy” that awaken the acoustic space.

• Development: accumulation of rhythmic textures, irregular pulses, and dynamic surges; the sound world becomes almost corporeal, suggesting breath, heartbeat, or ritual dance.

• Climactic Phase: complex density of overlapping layers — voices or resonances distorted beyond recognition — creating a sensation of trance or ecstatic saturation.

• Dissipation: gradual erosion of sound energy, leading to a return to space and silence.

The result is an organic form, reminiscent of Bayle’s “acousmatic journey,” but infused with Saint-Marcoux’s distinctly visceral sense of time — elastic, physical, embodied.

One of the earliest major electroacoustic works composed by a woman in Canada, marking a milestone in the history of North American electroacoustic practice, which bridges European acousmatic tradition (GRM) with Canadian experimentalism, forming a crucial link in the evolution of the Montréal acousmatic school. « Trakadie » stands as a poetic and powerful ritual, where the physical, the cultural, and the sonic converge. Micheline Coulombe Saint-Marcoux transforms tape music into a theatre of invisible gestures — a space of resonance, memory, and embodiment + she asserts that the electroacoustic studio was a place where women composers could articulate new forms of sonic subjectivity — tactile, spatial, and deeply human.

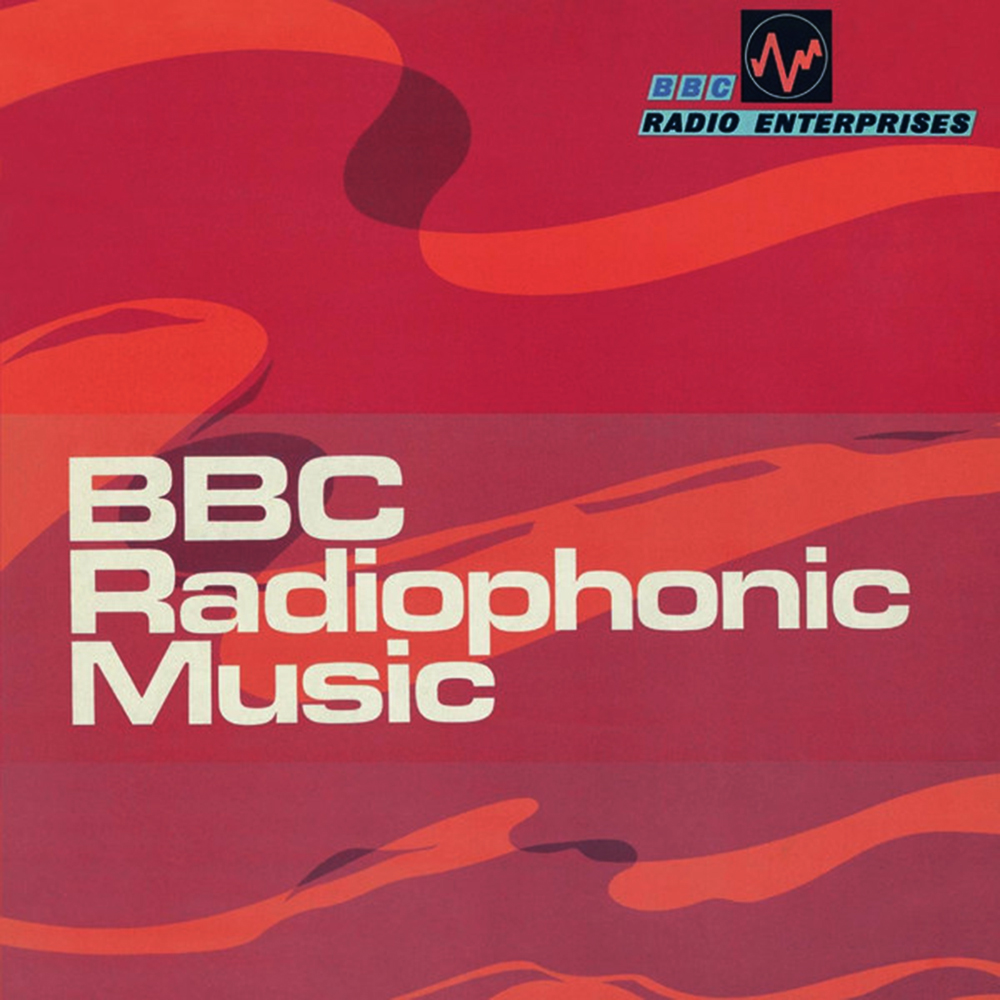

Delia Derbyshire – Pot-au-feu (1968/BBC Radio Enterprises)

The Woman Who Dreamed in Frequencies.

Delia Derbyshire is not a name but a signal —

a shimmer between worlds,

a mathematician who taught machines to dream,

a woman who recorded the sound of tomorrow before tomorrow existed.

And if you listen closely — beneath the hum of the city, beneath the circuits of your own breath —

you can still hear her voice, whispering through the wires:

“Everything vibrates. Even time.”

In the cold hum of postwar England, a woman began to hear time differently.

She was born Delia Ann Derbyshire in 1937, in Coventry, a city rebuilt from ashes and vibration.

While others saw factories and ruins, she heard harmonics — the hidden tremor of metal, the secret rhythm beneath dust.

Mathematics and music were her twin languages, twin obsessions; she studied both at Cambridge, as if to learn how to measure the unmeasurable.

When she arrived at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the early 1960s, she walked into a cathedral of tape loops and test tones.

There, in the flicker of oscillators and razor blades, she found her true medium: the ghost song of machines. She did not play instruments — she built worlds.

Magnetic tape became her staff, oscillators her choir, sine waves her dancers.

Each splice, each edit was a breath of creation, a heartbeat coded in current.

And then came the sound:

The theme to Doctor Who, a pulse from another planet. She did not merely arrange notes — she conjured a future. In that alien oscillation, the whole of British electronic music trembled awake. Science fiction became sound fact; electricity began to dream in human form.

But beyond the myth of the Doctor Who theme lies a thousand secret works — collages for theatre, radiophonic poems, musique concrète whispered to the walls of London’s studios. She called them “experiments,” but they were closer to alchemy: turning air into meaning, voltage into emotion, mathematics into ecstasy.

Delia lived like her sounds — precise and chaotic, ordered and uncontainable. She moved through the world like a waveform: sometimes sine-smooth, sometimes noise. Her work was often signed away to institutions, anonymous, archived, absorbed — but her frequencies escaped, like seeds carried by static into every ear that could still imagine.

Even as she left the BBC and vanished into quieter work, the hum never left her. Her life was a feedback loop — invention feeding despair, despair feeding invention — until silence finally claimed her in 2001. Yet the silence she left behind still resonates, infinite and alive.

« Pot-au-feu » (1968) by Delia Derbyshire is one of the most vivid and refined examples of early electronic tape composition from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. It demonstrates her extraordinary technical mastery, musical intelligence, and aesthetic subtlety — all achieved in an environment that was officially not meant to produce “music.” By the mid-1960s, Delia Derbyshire (1937–2001) had already become one of the most innovative figures in British electronic sound. A graduate in mathematics and music from Cambridge, she joined the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1960, where she quickly transcended its functional role of providing “sound effects” and “theme music” for radio and television.

The Workshop — founded in 1958 by Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe — was equipped with test oscillators, tape machines, filters, and reverb units, but lacked the kind of modular synthesizers available at academic studios in Europe (Cologne, Paris, or Milan). Working under severe technical constraints, Derbyshire became a master of tape manipulation — splicing, looping, reversing, filtering, and precisely editing layers of tone and noise to create rich musical structures from purely electronic or concrete sources.

« Pot-au-feu », produced in 1968, was originally made for the BBC series « Out of the Unknown », but it stands independently as a miniature electroacoustic composition, with all the hallmarks of Derbyshire’s craft: rhythmic vitality, spectral control, and structural elegance. Because the Radiophonic Workshop had no synthesizers at the time, every sound was created manually from tone generators, recorded noises, or modified instrumental fragments, then sculpted on magnetic tape. Derbyshire built her textures by layering short percussive bursts, oscillating drones, and filtered pulses, editing with millimetric precision to create rhythmic and harmonic coherence. Structurally, it prefigures later electronic sequencing, anticipating the logic of loop-based electronic music decades before digital sampling.

The title means “stew” and humorously reflects the collage-like nature of the work: a “mix” of timbres and rhythmic fragments cooked together with exquisite balance. Derbyshire achieves remarkable richness with minimal means. Her sense of spectral balance — high and low frequencies carefully counterweighted — creates a spatial illusion: sounds appear to move in and out of depth, as though staged in an imaginary acoustic space.

Unlike many contemporaneous male composers who pursued abstraction or serial logic, Derbyshire’s work is playful, tactile, and rhythmically alive. She turns laboratory sound into musical gesture, where studios in Cologne or Paris pursued system and theory, Derbyshire pursued intuition, imagination, and the sensuality of sound. Pot-au-feu is both a technical marvel and a musical miniature of wit and grace — a piece that proves Delia Derbyshire’s compositional genius.

Working with the most limited analog tools, she created a structure of rhythmic vitality and sonic richness that rivals the work of her celebrated contemporaries in academic studios. Historically, « Pot-au-feu » reminds us that the true avant-garde of electronic music was not confined to universities or European institutions, but also flourished in the unassuming corridors of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, where women like Derbyshire and Oram forged new sonic languages from tape, tone, and imagination.

Daphné Oram – Episode Metallic (1964/Paradigm)

Daphne Oram (1925–2003) was not only one of the first composers of electronic music in Britain, but also one of the earliest worldwide. Trained as a pianist and composer, she joined the BBC in the 1940s as a studio engineer and sound balancer — at a time when women were almost never employed in technical roles. Fascinated by the experiments of Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète in France and the Elektronische Musik scene in Cologne, Oram began, independently and in parallel, to explore what she called “pure electronic sound.” She worked after hours in the BBC studios, using test oscillators, tape recorders, filters, and reverberation chambers to create her own experimental sound pieces.

Her advocacy for a dedicated studio for electronic sound directly led to the founding of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1958, which she co-founded with Desmond Briscoe. However, Oram left the Workshop just one year later — frustrated by the BBC’s emphasis on functional “sound effects” rather than artistic composition. She went on to establish her own independent studio, Oramics Studios for Electronic Composition, where she developed her pioneering Oramics machine, which allowed sound to be drawn directly onto film to control pitch, amplitude, and timbre.

« Episode Metallic » dates from this transitional moment — composed during her final months at the BBC. It demonstrates her distinct musical voice, already oriented toward abstract, autonomous composition rather than utilitarian sound design. It embodies both Daphne Oram’s technical innovation and aesthetic independence, standing at the threshold between musique concrète, electronic abstraction, and sound design for broadcast.

As the title implies, Episode Metallic is built primarily from metallic sounds — struck, resonating, and electronically processed. Likely sources included metal percussion (gongs, cymbals, rods) recorded to tape and then manipulated through speed variation, filtering, echo, and reverb.

The work explores the spectral properties of resonance: sustained ringing tones, glistening overtones, and percussive attacks that decay into shimmering textures. The tape medium allowed Oram to magnify the microtemporal details of these sounds — stretching and layering their inner harmonics into a continuous metallic landscape.

The composition unfolds as a succession of sound episodes, each exploring a different aspect of metallic resonance:

• Attack and Resonance: abrupt metallic impacts followed by reverberant decay, introducing the raw material.

• Transformation: these resonances are filtered and overlapped, forming a quasi-harmonic spectrum that shimmers and evolves.

• Density and Release: the texture grows increasingly complex — metallic tones fuse into a mass of sound, then gradually dissipate into silence.

The piece is non-linear, without melody or pulse, but instead built around energetic transformations — an approach closer to the French acousmatic tradition than to the serialist systems of Cologne.

Timbre is the structural core of the work. Oram treats each metallic resonance as a living organism, exploring its attack, decay, and harmonic bloom. The title’s “metallic” quality becomes metaphorical: the sounds seem both organic and mechanical, hovering between nature and technology.

This timbral attention anticipates her later Oramics system, where she sought to compose directly with the morphology of sound — bypassing notation and traditional instrumentation altogether. « Episode Metallic » sits between musique concrète (use of recorded sound) and electronic synthesis (use of oscillators). Oram’s aesthetic resists the binary: she was interested not in raw recording or abstract tone, but in the transformation of real sounds into electronic form — “transmutation” rather than imitation. The metallic material carries symbolic weight: it reflects Oram’s fascination with technology as a medium of transformation, not domination. By sculpting the sound of metal — the quintessential industrial substance — she humanizes the machine, turning the mechanical into something sensuous and poetic.

Through its shimmering timbres and meticulous structure, it embodies Daphne Oram’s vision: that sound itself could be composed, shaped, and “drawn,” long before digital synthesis made such control commonplace.

Historically, it stands as a foundation stone of the British electronic tradition, alongside the work of Delia Derbyshire and the later BBC Radiophonic generation — but also as an early articulation of what we now call sound art: immersive, tactile, and conceptually rich.