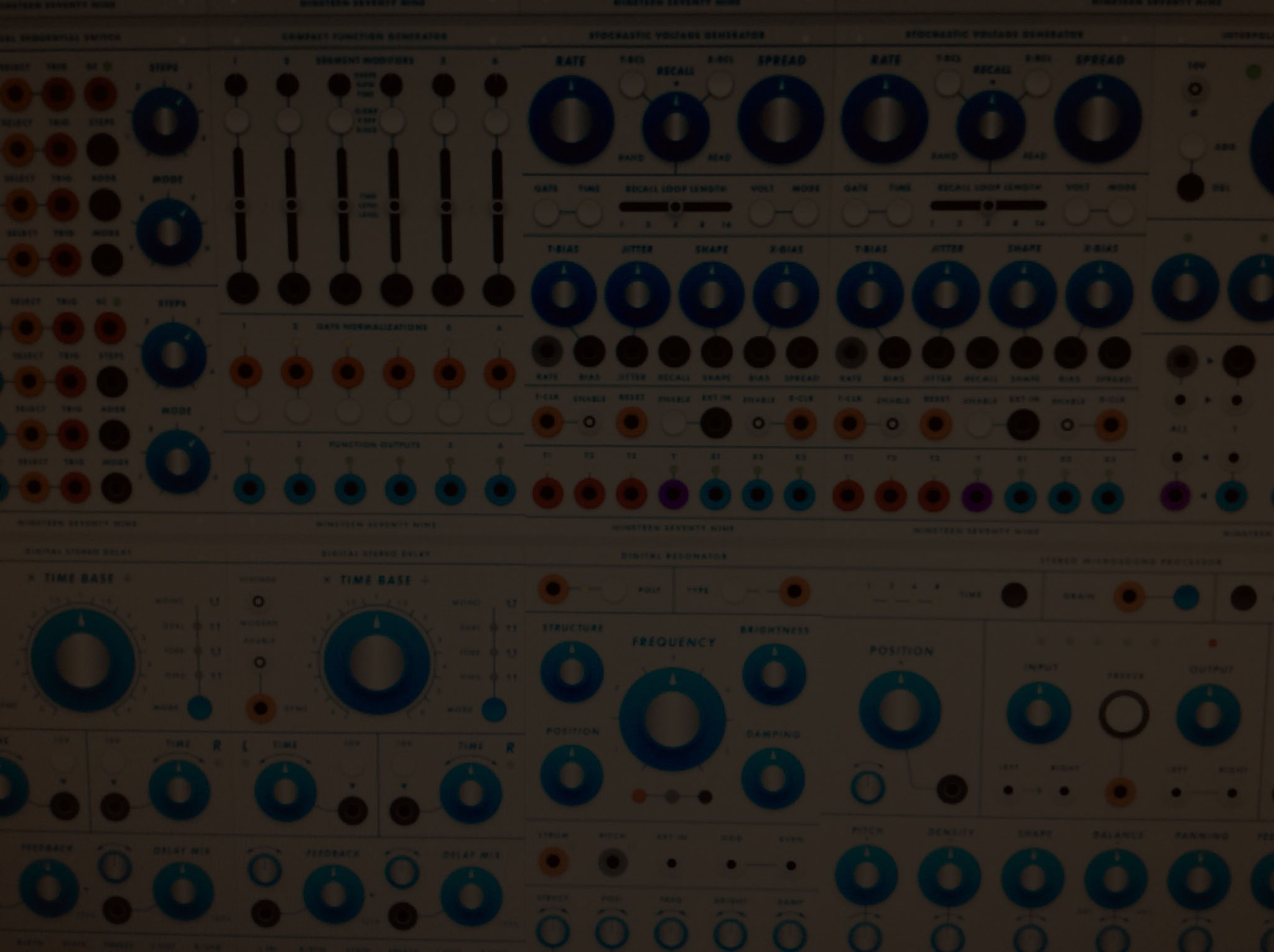

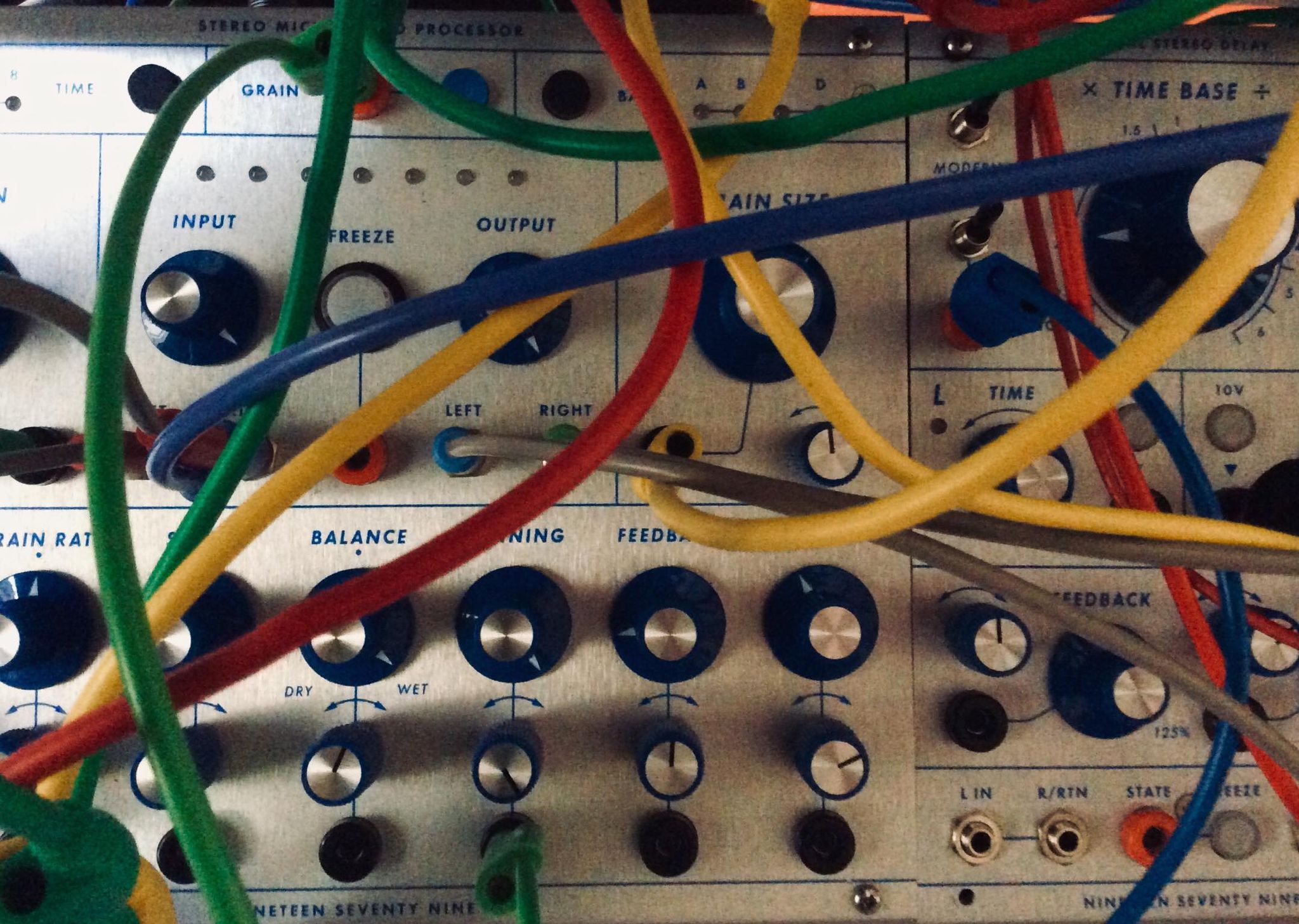

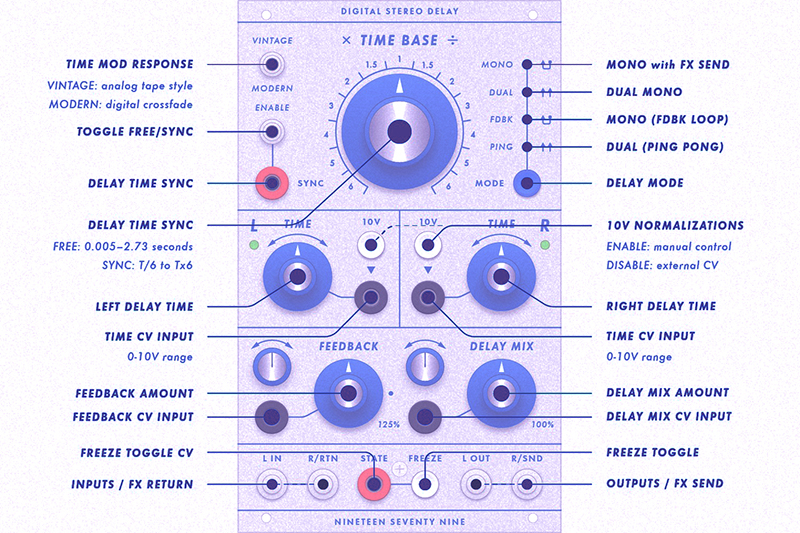

1979 is a brand whose particularity is to adapt some existing ideas to the Buchla format, they started offering a Dual Voltage Controlled Mixer, consisting of two independent four-channel audio mixers with flexible routing options and full voltage control + Digital Stereo Delay based on the Chronoblob V2 by Alright Devices. And then on to adapting the top-selling Mutable Instruments: Dual Algorithmic Oscillator based on Braids ; Modal Synthesis Voice based on Elements ; Clouds (Stereo Microsound Processor) offering Granular, Pitch Shift / Time Stretch, Looping Delay, and Spectral Processor. Digital Resonator based on Rings which uses digital signal processing to simulate vibrating strings and resonating membranes ; or the upcoming Stochastic Voltage Generator (based on Marbles) which is supposed to expand significantly on the Buchla 266 “Source of Uncertainty” to provide clock-synchronized random voltage generation for your Buchla-format modular system.

Nothing new though quite convenient for those of us reluctant to switch to Eurorack and use bad quality minijacks, or be forced to play a cramped interface esp. when 1979 respects the external design aesthetics of Buchla equipment allowing room to play the modules + his designs look and work very well with any 200 clone system.

Wes Milholen is passionate and his primary motivation was simply wanting new devices for himself :

I started out as a user of modular gear with no aspirations for becoming a designer of modular gear. That happened organically. Sometimes once you get an idea into your head the only way to get it out is to actually make the thing that you’re thinking of. And I felt that it would be worthwhile because I could apply my design background (in digital media and architecture) to a new field and learn some new skills in the process. I am very curious about how things are put together. I could simply buy modules and use them to make music, but I’m more inclined to drill down and deconstruct the devices themselves. And once you’ve taken things apart, you can reconstruct them according to your own preferences. That in itself is a form of creative expression not unlike musical composition. I’m just working with physical materials rather than the formless world of sound. So the “macro composer” metaphor seems somewhat accurate, but I think of it a bit more pragmatically. On a utilitarian level I’m simply an aggregator of ideas and raw materials which are transformed into devices that musicians can use for their own expression.

How did you first become acquainted with modular synthesis and the Buchla specifically?

The first patchable synth I owned was the Korg MS-20. I wanted to expand its functions so I started putting together a Eurorack system. Then I got a small Buchla 200e system but the preset functionality put me off so I didn’t end up keeping it. A few years later the infamous clones of the 200 series became available so I decided to build a new system with those. I really enjoyed working with that system but also wanted to expand its capabilities, so I started designing new modules which would be compatible with the Buchla workflow and aesthetic.

I watched an interview recently with Alessandro Cortini where he talks about how the Buchla has a magnetic and interactive quality that just makes you want to play with it. I had a similar feeling when I first became interested in Buchla gear. There is something about Don Buchla’s sense of aesthetics – the module layouts, the sense of hierarchy, the typography and nomenclature – that is unique among all modular formats. It feels like something you’re having a dialogue with. And maybe on some level it is a dialogue with Don himself. So that’s what drew me in at first. But then I wanted to go deeper than simply working with the system as a musical instrument. For me there is so much more to synthesizers than using them to generate sound. I am always thinking about synthesizers from an industrial design perspective and analyzing how the interface facilitates that dialogue between the designer and the composer.

Your brand is specializing in adapting some existing modules to the Buchla format. Why? And when did you build and/or design your first module?

The 200 series is something of a historical artifact, frozen in time at the end of the 1970s. Its limitations can facilitate focus and discipline but they can also be frustrating because we collectively have over half a century of gestalt knowledge about the possibilities of modular synthesis now. So when I started planning my Buchla DIY system a few years ago it was obvious that some new additions would be useful. The first Buchla-format module that I designed was the Dual Sequential Switch (DSS) which was intended to augment the functionality of the 245. Another idea from that time was the Dual VC Mixer (DVCM) which was released last year. It was inspired by looking at the Buchla 256 and wondering why there was no comparable module for mixing audio signals.

At some point I started thinking about adding a digital oscillator to complement the 258 and 259. Braids (from Mutable Instruments) was always one of my favorite Eurorack oscillators. Since all Mutable hardware and code is open source, it was possible to reinvent this module in Buchla format. I named it the Dual Algorithmic Oscillator (DAO) because I like the austere technical names of the vintage Buchla modules. Then I tried adapting a few other Mutable modules such as Rings and Clouds. But the most interesting thing about this process was not necessarily adding a certain type of functionality to the Buchla format. It was the challenge of transforming an existing Eurorack module into something that seemed aesthetically congruous with the historical precedents of the Buchla design language. Going through the process of designing these Mutable conversions was a good way to figure out what worked and what did not work with respect to that design language, because the overall parameters were already defined and somewhat inflexible. Although on some modules like the Stereo Microsound Processor (SMP) I did end up making significant changes so that I could address some of the common complaints about Clouds in its original form. Doing that inspired me to design another expanded version of Clouds in Eurorack format, which is the Supercell module released through my Grayscale brand. So that’s one of the positive feedback loops involved in doing these conversions – Eurorack to Buchla and then back to Eurorack again, learning new things along the way.

It’s no secret that many of the most successful Eurorack brands have borrowed heavily from Buchla (and Serge) precedents. If you look at the Make Noise DPO for example, the lineage is obvious. If the front panel layout doesn’t give things away, the phrase “Two Five Nine Was Here” is printed on the circuit board. Of course the DPO was released at a time when the 200 series was largely inaccessible to most people. Eurorack was the platform which merged all of these historical precedents into a common format, albeit one that’s a bit of a catastrophe when it comes to ergonomics, interoperability, reliability, and aesthetics. Eurorack offers every function that you can imagine but you don’t get something for nothing. There are always tradeoffs to be made. From a design perspective Eurorack is like a big city with a lot of signage and advertising competing for your attention. It seems that more people are gravitating to other formats now as they grow weary of inhabiting that space. The functionality of other formats is not significantly different, and the sound is not significantly different either. People are simply looking for better design. They want their instrument to make sense on a gestalt level. So that’s the main challenge for me as a designer: creating cohesion and consistency even when the circuits and concepts themselves have diverse origins. The modules have modern technology behind the panel but they need to look and feel like they’re from the 1970s so that there’s a seamless integration with the 200 series.

What does inspire a new module design?

There are many inputs into this process. One of my larger goals is to develop a complete system, so that’s a rough framework for where I want to take things over the next few years. Many of those ideas involve filling various functional gaps in the 200 series or upgrading some of the originals. But that’s very broad. I don’t really have a master plan for doing this just yet. The design process itself is actually more organic and not so goal-oriented. I have my Buchla system sitting in my workspace so I’m always staring at it and visually rearranging the locations of knobs, jacks, switches, etc. I think about inductive reasoning, which is the opposite of deductive reasoning. With deduction someone defines a problem and then uses a logical process to test solutions to that problem. Induction is more intuitive. You start with the solution and work backwards to see what problems it might solve. Sometimes I’ll think of an interesting module layout and then consider what functions it could perform. This is the opposite of typing out a list of parameters for a given module, which are then placed onto a grid, and saying that the module design is finished. That’s the left brain engineering approach, which is driven by functionality and features. The right brain approach is driven by open-ended curiosity and exploration. You want to make something look inviting and useful even if someone doesn’t know what it does. I’m always switching back and forth between these two approaches. Sometimes your subconscious is giving you the answers to questions that you haven’t consciously formulated and you should listen to those cues. I tend to follow this pattern no matter what I’m working on – music, designing a building, writing, coding, or other things. It’s important to develop a process that you enjoy and not just focus on the final product.

What has been your most popular design (or designs), and why do you think it (or they) became so successful?

Of the 1979 modules, the DAO has been the most popular thus far. I think it was successful in part because it actually cost a bit less than buying two Braids in Eurorack format. Even though Buchla-format modules are much more expensive to manufacture, in this case there was an economy of scale involved in combining two modules into one. From a functional perspective I think that oscillators, as the foundations of a modular system, are always appealing and introducing a digital oscillator with such a wide range of algorithms had a clear value proposition. Also there are only a few existing oscillators in the Buchla world, so it significantly expanded the sound palette of what was possible in this format.

What system do you dream of building?

I’m pretty much building it now by designing new 1979 modules. The Buchla 200 series is foundational for all post-1970s conceptions of modular synthesis and it’s very interesting to go back to first principles and use that raw material as the starting point. So my dream is to simply continue expanding the 1979 lineup and trying to retroactively imagine how the 200 series might have evolved. For me it’s a source of endless fascination and discovery. Eventually I would like to offer a complete system so there are still lots of ideas in the queue, but also a lot of question marks. So I’d like to keep this dream open-ended for now and see where the process leads.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? How do you explain that?

As someone who’s deliberately tried to simplify their life and avoid the more egregious traps of consumerism I think about this a lot. People joke about their “Eurocrack” addiction and although that’s a bit crude it does speak to the never-ending search for new sounds and techniques. One reason for this is that a modular system is never truly finished. You just run out of space, time, or money. There’s something inefficient about using modular hardware but the enjoyment you get out of that is somehow inversely proportional to that inefficiency. If there’s no end to sound, no end to creativity, no end to musical expression, then it’s difficult to use a fixed set of tools because new insights into your process mean changing the tools that shape that process. It’s just another type of feedback loop.

Another thing about Buchla as a format is that the physical size creates a limitation in terms of how large of a system people are willing to build. There are some monster Buchla systems out there but systems with 12, 18, or 24 modules seem to be the norm (thanks to the standardized 200e cases from Buchla). So with the new modules I’m designing I want to create more functional density. From the original San Francisco Tape Music Center modules to the Buchla 200e there’s a clear evolution towards greater functional density. That process is taken to an extreme in the Eurorack world, where quite a few modules have compromised their utility by shrinking everything down into a very cramped interface. That’s less of a problem in the Buchla world. I think when you drop four figures on a 200e oscillator you are not only doing so because of how it sounds. It’s also because you appreciate the ergonomics of the format, you’re inspired by the history, and you can justify making that kind of investment in an instrument that you will keep for years. I would like to design things that have that sort of longevity too.

Is there a type of module that you would like to build, but that is too expensive (or doesn’t have a big enough audience to support making it)?

I’m surprised to say that the answer is “no” – of course I do have to balance what I want to make versus what the relatively small number of people who are using Buchla systems might actually want to buy, but thus far I don’t think any of my ideas are so esoteric that they will stay on the shelf indefinitely.

Something I often discuss with Andrew Belt when we’re working on VCV Rack is the “UNIX philosophy” from the 1970s. This idea was intended for software developers but it has some clear applications to modular synthesis as well, since it’s about building small functional blocks rather than large monolithic systems and also thinking about where inputs come from and where outputs go. I don’t know if Don Buchla was inspired by this sort of thing but most modules within the 200 series have a very clear and specific role. They each have a personality and an obvious function. I think that’s a good precedent to follow. Don’t make any individual module overly complex. When the functionality being provided is unambiguous, people will clearly understand what it does and hopefully see its value.

Do you feel close to other makers and/or designers? If so, which ones?

I just mentioned VCV, which stands for Virtual Control Voltage. VCV is basically myself and Andrew Belt.

Andrew reached out to me about four years ago when he was just getting serious about the development of Rack and wanted to work with a designer who had experience in the modular domain. Rack is a free open-source modular synthesizer platform which has about 2,300 modules at this time. There’s a very engaged community around this software which includes many talented developers who are exploring every idea you could think of, from neural networks to voltage-controlled video games. When you don’t have the limitations and costs of hardware it’s very easy to create whatever you want and explore ideas that would probably not have any sort of commercial application in the hardware world. The rate of evolution in the Rack ecosystem, in terms of idea generation and iteration of known concepts, is much faster than hardware too. So this has been a very rewarding collaboration which has directly influenced my hardware design process – another feedback loop.

I also design module layouts for other hardware companies. The first such collaboration was with Paul Schreiber of Synthesis Technology. I think this started about eight years ago and we are still working together. I had an MOTM system back in the day so we had become acquainted. He was looking for a designer to help with new Eurorack module layouts. The existing aesthetic was already well defined, so I was mostly working within that design system. Somewhat similar to working in Buchla format, actually – working within a strict aesthetic system. So at this point I’ve designed the layouts for most of the Synth Tech modules other than the earliest ones like the Morphing Terrarium. This was my first experience with creating production files for modular synth front panels, which later informed the Grayscale alternate panels that I created for other Eurorack modules. And doing that eventually gave me the confidence to start designing my own modules, so this collaboration was pretty foundational for me.

There have also been many collaborations on projects which were never released. Tiptop Audio’s plan to convert many of Serge Tcherepnin’s 4U modules to Eurorack format was one example. I spent a lot of time deconstructing the original Serge grid, digging through old Serge catalogs, and learning everything about vintage Serge modules that I could. Even though this project was abandoned, it was a good exercise in taking concepts from one modular format (Serge) and recreating them in another format (Eurorack). I’m hoping to bring some of those vintage Serge concepts into Buchla format eventually as part of another collaboration that’s in progress. Another feedback loop taking shape.

Do you compose or perform music — or don’t you have time to do so?

I was recording things from a young age. I remember using tape recorders to capture video game music so I could listen back to it later without actually playing the game. The Casio SK-1 was my first synthesizer, I was about 10 years old then. I’m not really sure why my parents bought that because they were not interested in electronic music or synthesizers, though they did have a large record collection and some traditional instruments. Maybe it was just that post-1970s wave of cheap digital synths (which ironically killed off modular synths for a while). From there I started building a small setup based around a cassette 4-track and a drum machine. Then everything moved to the computer for many years but eventually I went back to hardware and started collecting analog synths.

I recorded a lot of diverse material but never did any formal releases. Just experimentation, learning, listening, following a subconscious process with no particular goals. Eventually a consistent aesthetic manifested itself and I started feeling confident enough to perform in public. After years of looking forward to performing I found that I didn’t really enjoy it. I wanted to be back home making noise in the studio or designing new things for the studio. I did have a few good shows with friends at odd venues like art galleries and book stores. As designing synthesizers has taken over more of my life I’ve had less time for music composition but that’s fine. I enjoy merging music, design, and technology into one all-encompassing project.

Do you have any advice you could share for those wanting to start or develop their own “Modulisme”?

If someone wants to get into making modular gear, they should be ready for a life-changing experience that is very demanding. Everything that can go wrong will go wrong. You have to accept that the fun part – sketching out new ideas, working on design iterations, developing the electronics, and getting that first prototype in your hands – is just one part of the overall effort. Once you get through all the manufacturing challenges and delays and you have that box of finished modules sitting in your office, you’re really just getting started. Now you have to deal with shipping, accounting, promotion, communications, making demos, writing manuals, updating websites, and so on. Also most people outside of the synth scene will have no clue what you are doing, and they get even more confused after you explain it to them, so it can feel very insular at times. But I enjoy overcoming those challenges and it feels like many threads are flowing together into one big meta-project. It’s very rewarding to get through this arduous process and hear people making music with something that started as a page in my sketchbook.

What have you been working on lately, and are you designing anything now, or investigating any areas of interest that you can share with us?

Mostly I’m eager to get the modules I’ve already announced out into the world and move on to new ideas. The next release will probably be the Stochastic Voltage Generator (SVG), which is based on Marbles from Mutable Instruments. This module borrows heavily from the Source of Uncertainty but adds a lot of additional control and complexity. And I’m hoping to finish that Dual Sequential Switch idea from four years ago, which people are still asking about. Lately I am also thinking about how some of the core 200 series modules could be expanded or complemented. I’m not interested in making exact clones of vintage modules but there are many possibilities for incremental evolution and increased functional density.

All of this might lead someone to ask: what makes the Buchla the Buchla? Might a day come when you have a “Buchla” system which doesn’t have a single Buchla-branded module – whether vintage, clone, or 200e? That might be possible, and it would not necessarily be a bad thing. I recall the prose poem written by Don Buchla and Charles MacDermed which ends with “THE ELECTRIC MUSIC BOX PLAYS ON AND ON.” It’s truly impressive that after more than half a century, Don’s inventions continue to be used in more or less their original form. We should all keep playing, hacking, modifying, and reinventing the Electric Music Box so that it can become even more relevant and accessible than it is today.

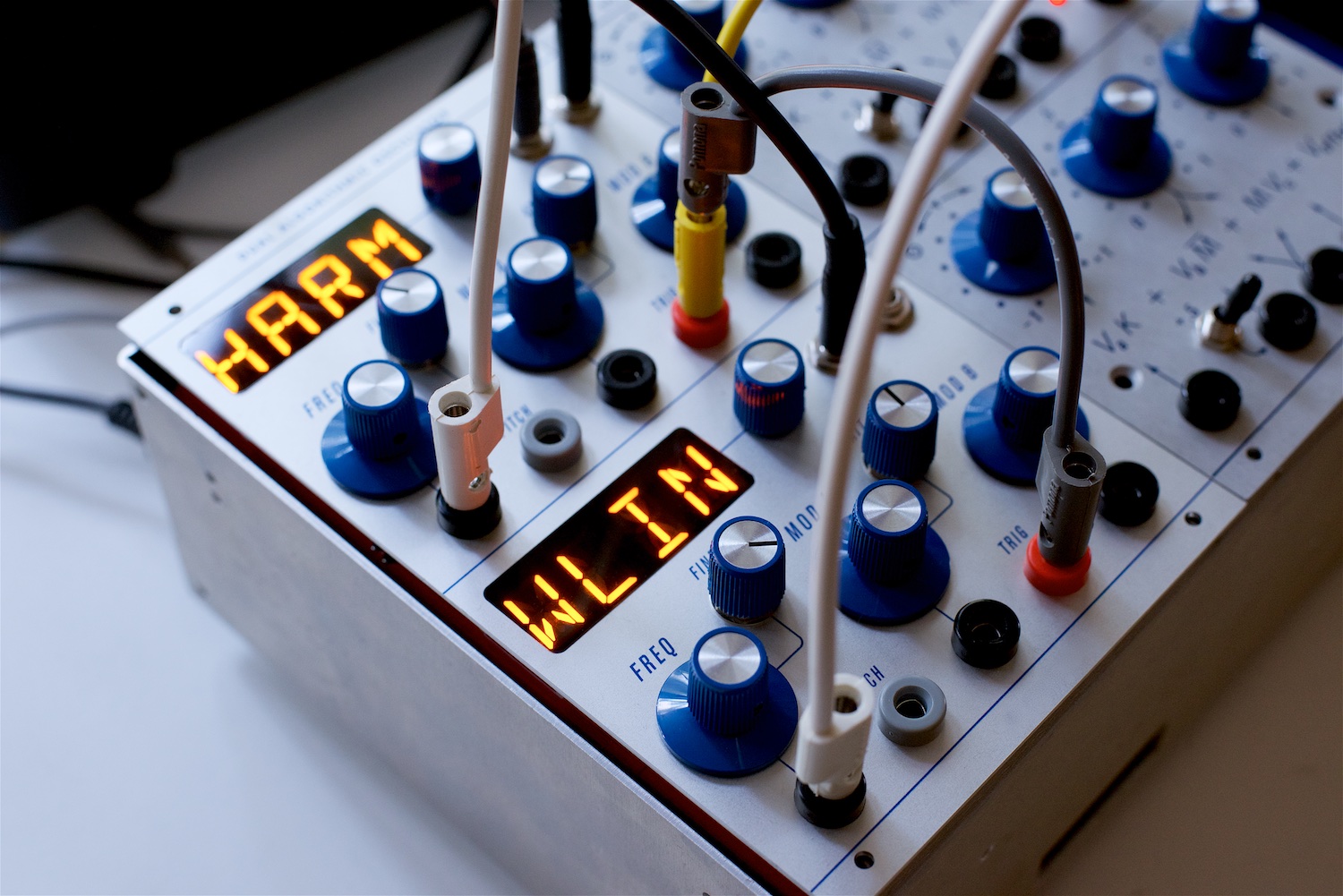

Wes Milholen demo his M.S.V.

Augustus Green (The Galaxy Electric) plays the SMP

Some more demos from Wes Milholen