Make Noise was founded in 2008 by Tony Rolando, a self-taught electronic musical instrument designer who got started by obsessively reading amateur radio books at the public library, building electronics for artists, working for Moog Music, and playing in bands for many years.

Heavily influenced by Buchla and Serge he managed to design and build some pretty strange, but thoughtful modular synthesizers.

Tom Erbe has ben deeply involved and dedicated to electronic and computer music research, and creation.

He invents computer music software and hardware, most notably the sound processing application SoundHack, the many soundhack plugins, and several ground-breaking synthesis modules developed with Make Noise Music.

We see our instruments as a collaboration with musicians who create once in a lifetime performances that push boundaries and play the notes between the notes to discover the unfound sounds. We want our instruments to be an experience, one that will require us to change our trajectories and thereby impact the way we understand and imagine sound.

Also, we think what we do is fun and we hope you like it, too.

Can you please briefly talk about your background?

Tony Rolando: I am a musician and self-taught analog electronics engineer. I got my first synthesizer manufacturing experience working for Moog Music and went on to found Make Noise Co. February of 2008.

Tom Erbe: I’m a professor of electronic music at UCSD. I’ve been a musician, music software and hardware engineer, DJ and recording engineer. I have a computer engineering degree from UIUC, but self-taught after that. I’ve made most of my electronic music tools under the name SoundHack (since 1991).

Would you introduce us to the MN team? How many employees, who? Doing what?

T. R.: The production crew is Jake, Jon, Mike, Newt and Sam. They purchase, receive, build, calibrate and test everything we offer. Meg is our shipping person. Sales is handled by Rodent. Many of the day to day tasks are handled by our Office MATHS, Natasha. Technical Support and service is handled by Devin with help from myself and Walker.

The media team handles all photos, videos, website and social media. They are Walker, Pete and Lewis with guidance from myself.

Our CEO Kelly steers the whole operation and is largely responsible for the growth that allows most people to actually have and hold a Make Noise instrument.

I guide the development of our instruments, working with Tom where digital signal processing is required and the entire crew assists in beta testing and development.

Tom you had originated Sound Hack and developed many essential plug ins, how did you meet and start collaborating with MN?

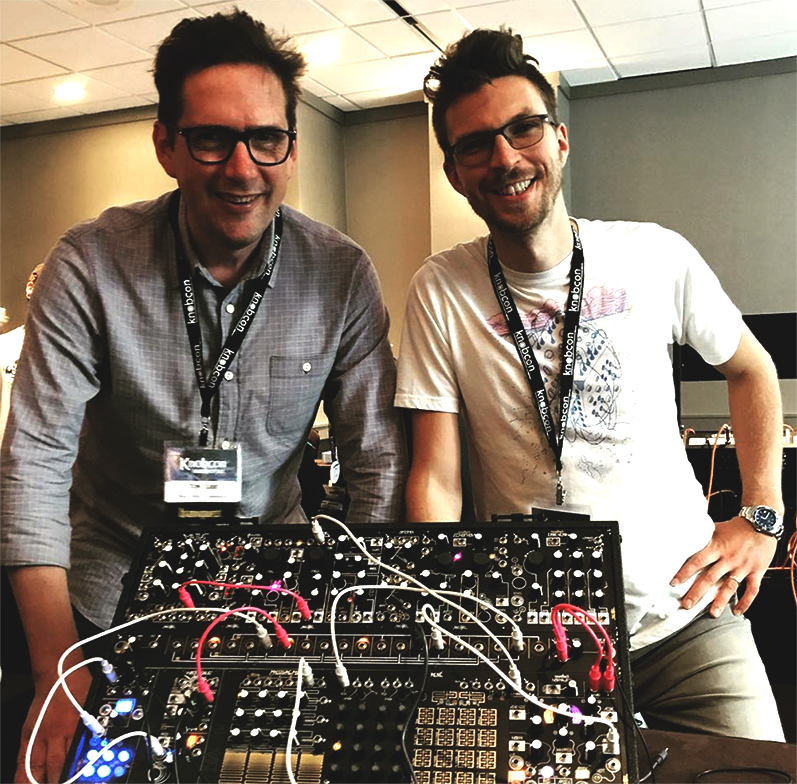

T.E: I met Tony at the NAMM show when he was introducing the Phonogene. I thought that was really cool, and we had a nice talk about it’s design, granular synthesis, the modular scene, etc. I told Tony about my plugins, which he checked out later.

I got a call from Tony after the NAMM show and he invited me to collaborate on a module, which became the Echophon.

And as an extension of that question—what is SoundHack, and how has it changed over time?

T.E: That’s a big question, but I’ll try to succinct. SoundHack is a freeware Macintosh application that I wrote in 1990-1. I wanted to make unusual spectral processing available to me and others. It contained soundfile convolution, phase vocoder time and pitch changing, binaural filters, varispeed and other filters. In 2000, I decided that plugins would be more modular and accessible, and started releasing these under the soundhack brand.

I’ve made about 18 of these, and have generally built things I need in my production work.

From your perspective, is there an advantage in the process of designing audio tools for software versus hardware platforms or is that the hardware you may prefer?

How do your approaches differ in each context?

T.E: Both plugins and modules allow me to concentrate on one audio process, and give that as much depth as possible, so they have that in common. In general, software people want repeatability and hardware people what interaction/playability, so I have to follow that in my designs. With plugins there is much less code to create, as the format is so defined (I wrote one plugin at a garage while waiting for my car to be repaired). With hardware, I need to write code for everything, from the knobs to LEDs to bootloader. I do prefer hardware though.

I enjoy playing with hardware so much more, and because of this it’s much more satisfying to create.

Where, when and how did you first become acquainted with modular synthesis?

T. R.: I saw Jim O’rourke performing on a Doepfer P6 system at Lounge Ax in Chicago. My friends and I called it the electronic music suitcase. It looked like a suitcase with wires poking out of it. He set it on a crate and played it. That was maybe 1996? Around 1989 I had found and purchased a copy of Morton Subotnick’s “Silver Apples” at a local LIbrary record and book sale, but I had no idea what instrument I was listening too as the liner notes just listed it as “Buchla” and the library had no books on the shelf that explained what the “Buchla” was and thus began my quest to learn about and to find the “Buchla.”

T.E: This one’s going way back. I remember watching “The Monkees” with my sisters in the late 60s – we were all music fanatics. This was the episode which had Frank Zappa as a guest. In it, Mickey Dolenz sang a cool song while playing a Moog modular. After that, I sought out any music with a synthesizer on it, from Roxy Music’s “Editions of You” to Parliament’s “Flashlight”.

I learned how to play a modular when I was the studio director at the Center for Contemporary Music at Mills College.

They had a Buchla 100, an Arp 2600 and a Moog IIIp. The first modular I had myself was an Aries 300.

When did that happen? When did you build and/or design your first module?

T. R.: I recall by the late 90’s the internet had made information about modular synthesizers more widely available and I began building PAIA kits for my modest synthesizer system.

You 2 witnessed Modular Synthesis gain more and more interest, how do you feel about that? In a way it is very capitalistic, creating a demand/needs which most wouldn’t have… Shouldn’t have? In a sense that many spend days watching demos, thinking of which modules they may buy next rather than fully exploring the ones they have… Marketing prevailing.

MN being real good at marketing. Where do you stand?

T. R.: Nobody working at Make Noise has formally studied marketing.

We just do what we are passionate about. Most YT videos are based on topics we come upon in our conversations around the office. Instagram posts are seen largely as a creative outlet. Anybody at the company can build a patch and submit it for a post. We are currently building a livestreaming station that will allow any member of the MN crew to go live and patch or talk about synthesizers any time of the day.

If an artist feels they “…spend days watching demos, thinking of which modules they may buy next rather than fully exploring the ones they have…” that is procrastination of their own making. It is easier and often more fun to think about making art than to actually make art. This phenomenon is seen in nearly all of the arts and is not unique to modular synthesizers.

Serge was interested in the natural sound of the transistor, an inherent sound in the machine raw and unpolished, wild when played, very much with a life of its own.

Buchla is more of a concept of functions in a tight package, so well defined and thought with a musician’s perspective in mind. It’s an instrument allowing space to play. I am attaching great importance to my gesture in composing. How I do approach a system and my moves within… With it… I like to be hands on and Eurorack does not allow much space.

Do you attach importance to space, size or is that functions which matter most?

T. R.: I am often told Make Noise is at odds with the trend in eurorack toward smaller, more functionally dense but congested systems. We are not going to make 2hp sized modules. Make Noise has only ever made a handful of 4hp modules none of which had any knobs or buttons. I’m just not very excited about cramming too much functionality into a tiny space. All that said, the small form factor of euro rack means even a spacious eurorack module will feel cramped compared to a Moog format module.

West Coast, East Coast.. Your DPO owing so much to Buchla and a little to Moog… You coined 0 Coast… Shall I understand that MN is a revolution or simply trying to bring the best of both worlds?

T. R.: I am just drawing from my own experience. I learned alot about synthesizers through my work at Moog, and thus the Moog design philosophy had a big impact. All the while I dreamed of the Buchla, it fully captured my imagination and thus had a big impact. The 0-COAST is just the culmination of these experiences.

From the beginning you showed an attraction to a certain type of sound, choosing to recreate/adapt functions from mythic systems like Buchla and Serge. Could you tell us more about those choices?

Why? What attracted you to those 2?

T. R.: I have some Serge panels now and it is a wonderful sounding instrument, but the Serge did not initially capture my interest and inspire me to start Make Noise. That initial spark came from the Buchla 200 and Music Easel. It began with that Morton Subotnick record I found. I searched every library I walked into for information about Buchla. Once I had access to the internet I started to find bits and pieces and most importantly, pictures of the 200 series modules. Peter Grenader (of Plan B synthesizers) recommended to me the Barry Schrader record “Lost Atlantis” which further deepened my interest in the Buchla 200 system. I would stare at the photos for hours and dream up functionalities and sounds they could make. It was not until years into the operation of Make Noise, that I got to actually play a Buchla instrument. Alessandro Cortini brought his Music Easel to a small gathering in Chicago. He had headphones plugged into it so we could all just play and explore it. A few months later a very kind fellow in Chicago loaned me his 200e system after a Trash Audio synth event. I had gotten snowed in, flight cancelled and was sitting alone in a friends apartment for a couple days and this fine person delivered the 200e to me to explore as I awaited the blizzard to pass. Thank you XART.

On one hand you said that you do prefer Analog but your most innovative modules are digital, would you explain why?

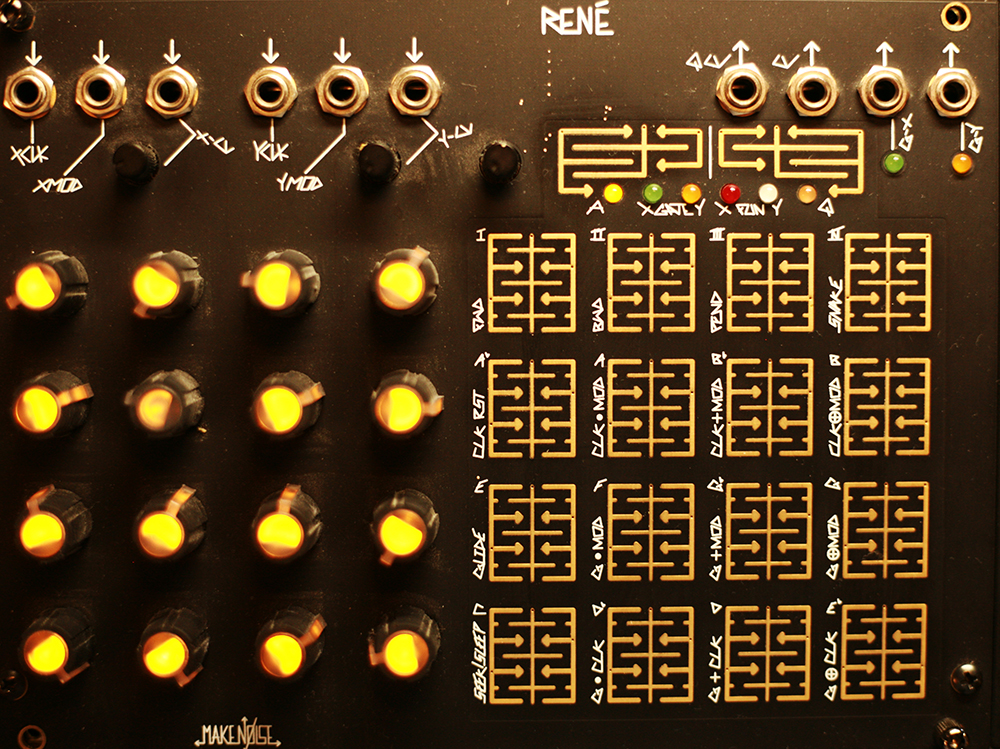

T. R.:The desires of synthesists breeds quite a bit of innovation and for the past decade synthesists have been obsessed with digital signal processing and so I try to satisfy their desires by working with DSP wizards such as Tom Erbe. I do think our QPAS filter is somewhat innovative in its approach to analog filtering, but not nearly as innovative as something like the René is to the analog sequencer… but really how does it matter that René is digital? It functions as an analog device most of the time. You could really say the same of the Erbe Verb.

Tony you chose to invent a full-system, a complete instrument that fully represents MN : the Shared-System.

Was that the first big step for MN being able to offer enough modules to communicate with each other and achieve a result being impossible by other means? Once that dream has been completed how could you go further on?

T. R.: The Shared system was the first system, but it was not arrived at as something Make Noise would offer to customers. It was developed as part of a music project. I put the system together and the artist Surachai curated several other artists to create new music all utilizing an identical framework: Shared System recorded live to stereo two track and arranged into final pieces for release on 7″ records. The goal was to show how the modular synthesizer as an instrument was truly capable of allowing an artist’s unique voice to shine through. I feel the project was very successful in doing exactly that. Interest in the system built slowly and we eventually offered it as an instrument.

Moving beyond the Shared System has been a combination of further developing existing concepts (René 2, Morphagene) and adding new concepts (Erbe Verb, TEMPI). Interest in the Shared System is still high, but unfortunately we have not been able to acquire the parts to build them for 2 years.

Any symbolic in choosing to use Gold?

T. R.: Not initially, although lately I suppose it could tie in with some of the alchemical symbology that informed the Strega development.

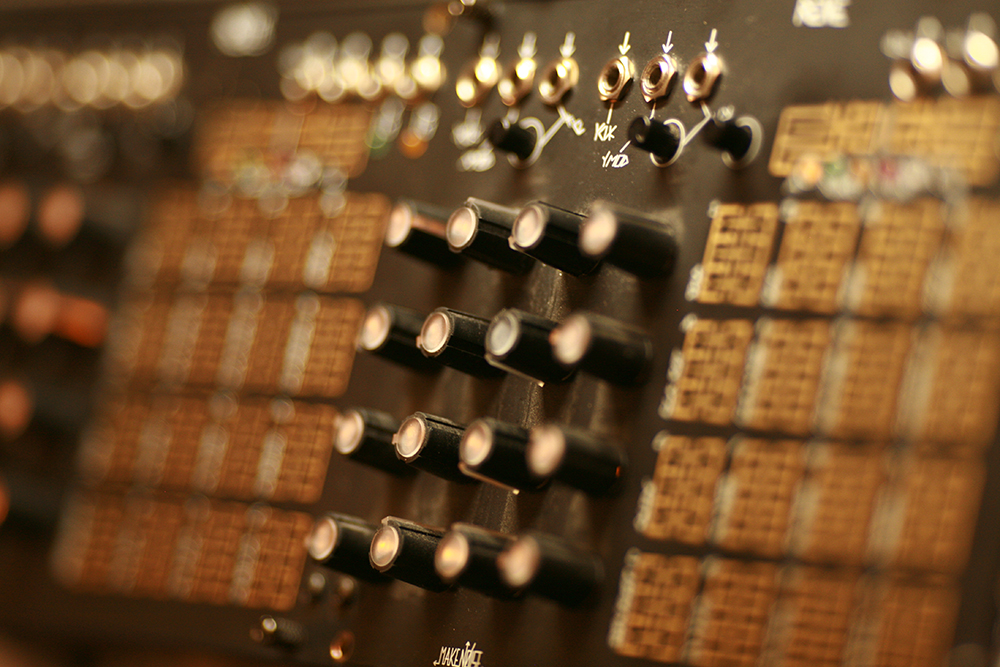

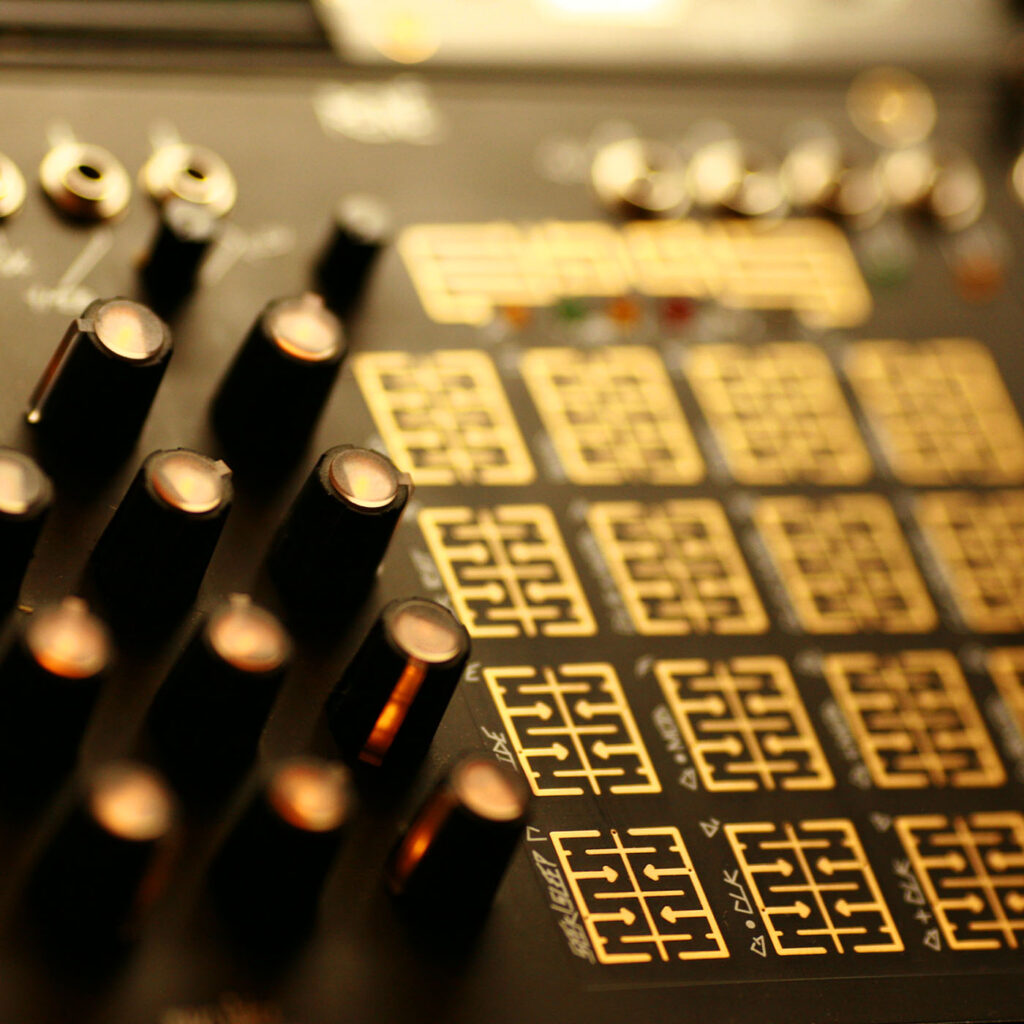

Initially I chose it because it was the finish that would be best suited to long term use in the field on modules where it is touched such as René and Pressure Points.

It is important to stress, that back when most systems were aluminium, Doepfer like, MN initiated the craze around black-fronted systems. You chose to invent your symbols and terms which contributed to your originality but may create confusion for users.

Retrospectively do you think it was the best choice?

T. R.: The symbols and terms I have invented have shaped how people learn and interact with the Make Noise instruments, this is by design and I enjoy seeing how people interpret the instruments. Unfortunately it is not possible for me to understand a parallel timeline where I presented the instruments with more scientific or literal symbols and terms so I cannot tell you if it was the best choice.

Potentially the music created with these instruments would be quite different if they were presented to the user in a different way.

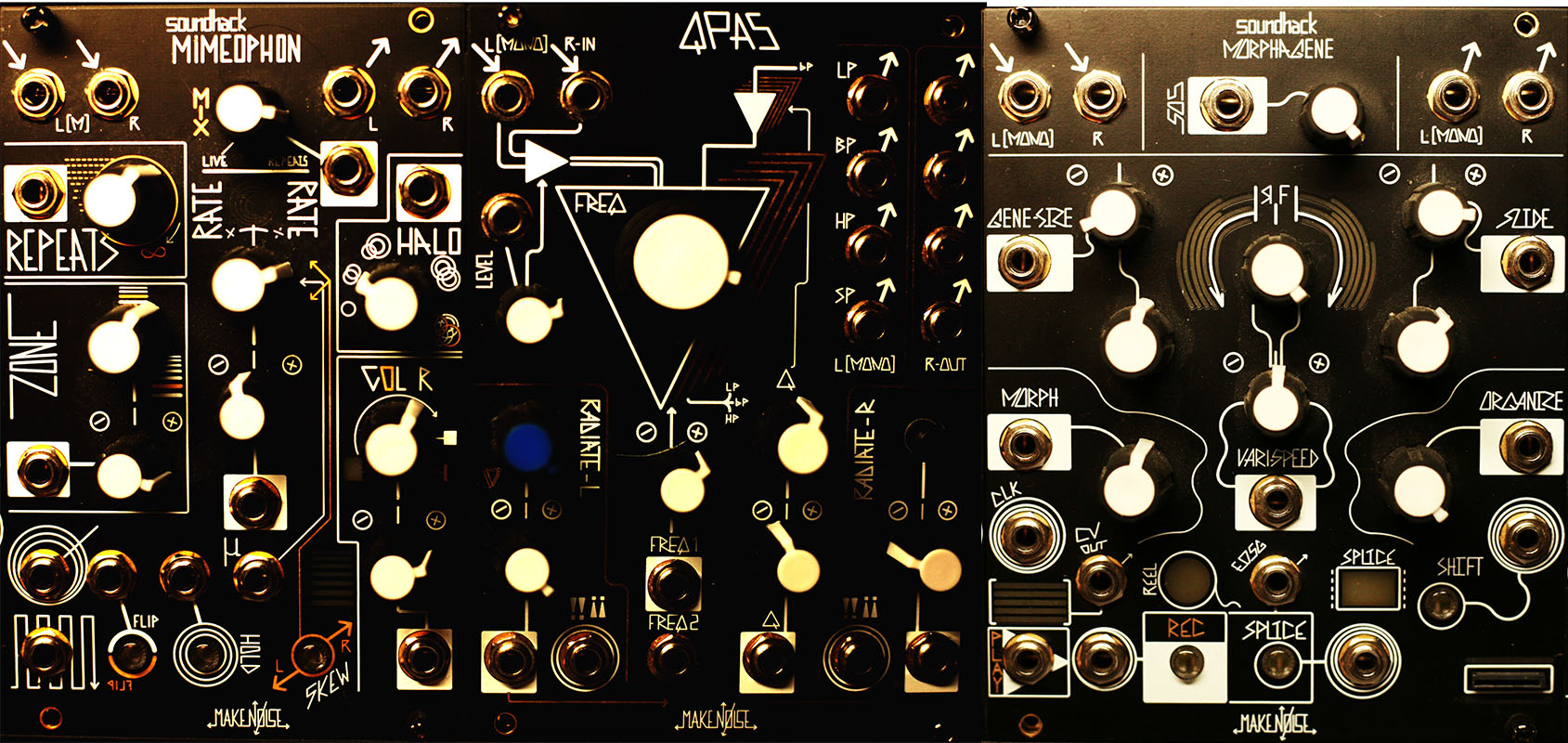

Tom you brought the Telharmonic, Echophon, Erbeverb, Morphagene and Mimeophon.

Can you tell us about those?

T. E. : We always talk about at what kind of sonic possibilities are missing in Eurorack and also can only be made digitally. This was definitely the case when we made the Echophon, Erbeverb and Telharmonic. In all of those I started with a basic concept – an aggressive pitch shifting delay, a modulatible resonant reverb and a compact additive harmonic oscillator – and complicated the design by adding different internal characteristics, more parameter control, etc. Usually during the process I research previous devices by reading patents, AES papers, circuit diagrams, computer code, and in some cases, analyzing them by sending in test signals and crunching numbers in Matlab. For the Morphagene, I wanted to add my own take on the digital looper – sampler while remaining familiar to Phonogene users. For the Mimeophon, I wanted to create a very lush delay that could do all my favorite delay effects well: karplus-strong, flanging, chorusing, tape delay, complex rhythmic sync. I was trying for the best of a Space Echo, Effectron and Super Prime Time in single module.

How do you both cooperate?

T. E. : We talk a lot about the initial design. Sometimes I propose several ideas, sometimes Tony challenges me to design something. We then work on the basic hardware and front panel needs so that Tony can build prototype hardware. When I get the hardware I spend a couple months trying to build code that has most of the sounds I like, and then I send it back to Tony. He, Walker and the rest of the gang at Make Noise give me a lot of feedback on the sound and the playability, and I make revisions until we all think it’s a great module. Finally, we beta test it for months.

What motivated you to become an electronic circuit designer?

T. R.: Curiosity, boredom, the desire to play interesting synthesizers. When music wasn’t going so well I took things apart and studied how they made or modified sound.

T. E.: It’s in the family. My grandfather was a radio broadcast pioneer in the 20s, my great uncle did marine radio on Mackinac Island, guiding ships, and gave me a signal generator, microphone and oscilloscope when I was 11 or 12. I became the technical director of my high school radio station at 15 and soon found I had to build and repair electronics (power supplies, preamps) to keep us on the air.

Is circuit design a natural extension of composing for you? Are you in some ways a “macro-composer” when you design tools that composers use to compose?

T. R.: Never thought of it this way, but with the Strega compilation (a collection of music we have curated where artists are using the Strega) and the Shared System Series it could be interpreted in that way.

I do feel that each instrument presents different paths for the players. The way I would compose using the Buchla system is quite different from how I would compose using an Oberheim Xpander and a midi sequencer, and furthermore the Shared System… even though at their cores, in the most general terms, these instruments are not so different.

T. E.: Yes, absolutely. For me instrument design is a creative act. However, it is more like composing an experimental piece of music – creating a structure that contains multiple pathways and musical possibilities.

What does “playing a modular” actually means to you?

T. R.: Creating, or further processing, sound with a modular synthesizer.

T. E.: Same here. It varies for me from improvisation to highly predetermined use of the modular.

Do you compose or perform music — or don’t you have time to do so?

T. R.: I have been recording a lot of music for the first time in over a decade. I have a record coming out this fall on Important Records. It is titled “Breakin’ is a Memory.”

There will be a video release accompanying the record. I have a couple of cassettes coming out soon as well. “Old Cool Echoes” (Cassauna) and “Multiple Futures” (Aventures). All very delayed due to pandemic style manufacturing. I am currently recording a Shared System series collection that I will probably release on Make Noise Records if we ever get that going again. I will perform a patch from time to time at something called “Modular on the Spot” but I am no longer a touring musician.

T. E.: I do from time to time. Usually performing other composer’s music. I performed electronics on Alvin Lucier’s “So You” a couple years ago. I’m about to release my version of John Cage’s “Williams Mix” on bandcamp. I also created a spatial version of Jim Tenney’s “For Ann (rising)” for the Toronto Biennial in 2019.

Which pioneers of modular synthesis influenced you, and why?

T. R.: Don Buchla and Bob Moog as I previously explained. Another I would add is Grant Richter. His Wogglebug (which Make Noise licenses as the Richter Wogglebug) is very exciting and being able to call him and talk to him about the design was very informative. I developed the RxMx from a circuit idea Grant published years ago. I believe Grant is one of the greatest links between 70’s modular and the eurorack of today.

T. E.: Same here, I also recommend studying the designs of Harold Bode, Gordon Mumma, David Tudor, Michel Waisvisz, Stanley Lunetta, Marvin Minsky – but this list could go on forever!

You are interested in innovation, new sounds thus what does inspire a new module design?

T. R.: This has changed over the years. I am always chasing inspiration, and inspiration is always changing forms before me, thus confusing me and making its capture tough. Listening to music is largely what has informed and inspired my design over the years. I am not currently excited by the pursuit of technological development for the sake of bleeding on the cutting edge.

T. E.: I agree completely. And generally inspiration leads to innovation. That said, I can get inspiration thinking about sounds that haven’t been heard, new ways to perform, new kinds of music. I guess speculation often leads to inspiration for me.

Is there a type of module that you would like to build, but that is too expensive (or doesn’t have a big enough audience to support making it)?

T. R.: I think we are currently developing exactly that! I think the confidence to chase after big ideas like this one is directly tied to the lasting support and interest from customers. I had always assumed the interest would wane by now, but it continues to be strong.

T.E. : I wouldn’t mind doing something that combines machine learning, a huge library of sounds and various types of concatenative synthesis. I’d like an ambisonics module that could drive at least 8 speakers, and maybe some binaural spatialization – but I think that’s a very niche idea.

Do you feel close to other makers and/or designers? If so, which ones?

T. R.:In the early days of Make Noise I was talking to Scott Jaeger (Harvestman/ Industrial Music Electronics) quite a bit. We would chat about module design and manufacturing processes. Scott is one of my favorite module designers. Mike Brown (Livewire) was very helpful to me early on. Danjel (Intellijel) and I collaborated to design, test and get into manufacture the jack that nearly every eurorack manufacturer uses today. I really like to see Dan (4MS) and Will (WMD). I am always happy to see Dieter Doepfer at an event. Watching him patch one of his Monster Cases is a joy. I don’t feel super close to most of the designers out there today, but there are many that I have met and I truly enjoy seeing. The folks over at ALM, THONK, Music Thing Modular are really fun to talk to. I saw Tom from Music Thing give a really wonderful presentation a few years ago at Machine in Music and his recent interview in Waveform Magazine was a good read.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming modules?

T. R.:In the last few years we’ve made it a habit at Make Noise to not discuss developments in an effort to avoid generating teasers.

Could you please share a playlist of some of your favorite composers/albums using your instruments?

T. R.:In no particular order:

Robert AA Lowe “Vanishing Earth”

Alessandro Cortini “Spie”

Hypoxia “Division of Trust”

Caterina Barbieri “Ecstatic Computation”

Evan Caminiti “Varispeed Hydra”

Richard Devine “Creature”

Kangding Ray “Cory Arcane”

Tim Hecker “Virgins”

Sam Prekop “Comma”

Second Woman “Second Woman”

Hélène Vogelsinger “Contemplation”I’m definitely forgetting some great ones…

Do you have any advice you could share for those wanting to start or develop their own “Modulisme”?

T. R.:Think about everything that has deeply moved you in your music listening and performing experience. People think it is funny that I often cite Eddie Van Halen as a deep early influence, but no other popular musician was playing such unique looking instruments in such a wild and untamed style when I was a kid. At least not on the radio where I lived. He truly lit a fire in me that burns to this day. Find those touch points, those moments of pure inspiration, capture them in your mind and meditate upon them and let that guide.

To know more about Make Noise