Allen Ravenstine was a key figure in the developing art and music scene in Cleveland in the early 70s. Working alone with an early analogue synthesizer, sans keyboard, and a four track tape recorder, he made a series of compositions.

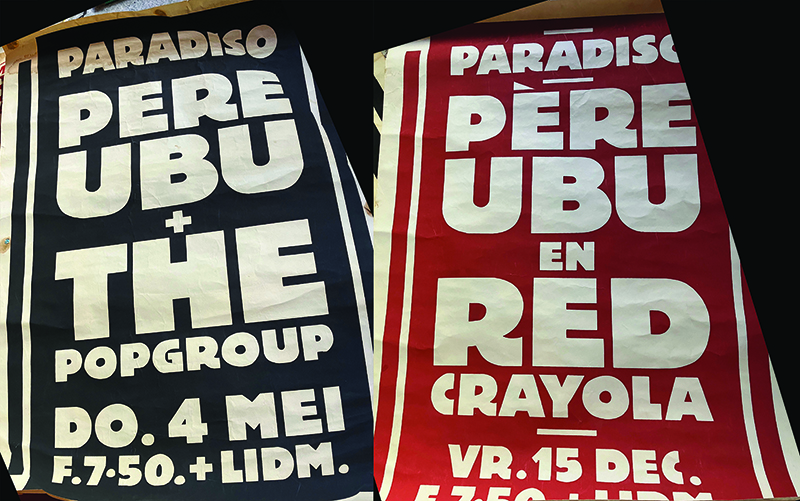

In 1975, one of those compositions titled Terminal Drive got him invited to join a group that was forming called Pere Ubu. That group’s membership changed over the years and eventually included Mayo Thompson who had founded the group Red Crayola in Texas in the 1960’s. During one of Ubu’s breakups, Ravenstine worked for a time in a reformation of Red Crayola both recording and touring. In 1991 he recorded his last album with Ubu and then left music to become an airline pilot.In 2013, an invitation to contribute to “I Dream of Wires: The Modular Synthesizer Documentary” led to the recording of an impromptu duo performance on the EML-101 and 200 synthesizers, with Robert Wheeler who had replaced him in Pere Ubu. Culled from that session were a pair of albums entitled “City Desk” and “Farm Report”, which were self-released in 2013. The producer of those records, William Blakeney, closely associated with the Electronic Music Foundation, encouraged Ravenstine to return to composing. About a year later, Blakeney produced “The Pharaoh’s Bee”: Ravenstine’s first solo project since the work he had done in the early ‘70s.

On June 29, 2018, Ravenstine released “Waiting for the Bomb” and he and Blakeney have worked together on a series of albums since that time.

The analog abstraction for which Ravenstine became known remains a significant part of his current sound palette, but recent years have seen him turn increasingly toward outlandish eclecticism as his foundation.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

New releases on ReR Megacorp will be “Wallflower”, a story I wrote and read over a soundtrack. “Harbor Lights Ragaas” which I worked on with Tony Maimone, produced by Bill Blakeney who played a major role. I work with Bill on most of my projects. And the release of material I made over two days in a studio with my original synthesizer an EML 200 built in 1971 or ‘72

You started playing in the 70s joined in the first line up of the cult band Pere Ubu. How was it back then, can you share good anecdote, great memories?

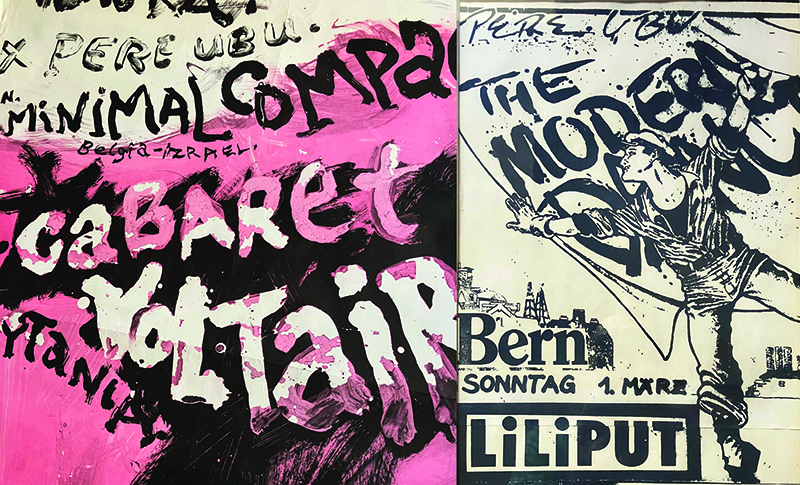

The European tours always included Amsterdam and playing in Amsterdam always included playing at the Paradiso. The Paradiso had once been a church but was taken over by squatters in the late 60s and then taken over by the city in 1968 and operated as an entertainment center. It backs up to the Singelgracht canal nearly across from the Rijksmuseum. It was also a place where hashish could be bought and used legally. In fact what was bought there had to be consumed there. We always thought that was a method by which the city could control the use of drugs by the city’s young people. Don’t know how well it worked. I do know that whenever we got into Holland there was a lot of hash around and sometimes when we were leaving a lot had to be consumed in a hurry.

The dressing rooms were in the basement of the church and it was an old church and the basement was a long way down a very narrow set of stairs. There was a print shop down there and an old hippie who was more like a gnome who lived down there and made all of the posters for all of the shows at the club. They were all very simple with basic colors but, they were classic.

The main room of the club was a the large open space where the pews had once been and while there were no seats, there were many mattresses spread around. Of course the audience was always very stoned.

Europe’s electricity is 220 volt power and so I had to carry around a transformer which was a heavy primitive looking thing made out of steel with parts of it wrapped in electrical tape. At midnight in those days which were the late 70s to the late 80s, the streetcar system in Amsterdam shut down at midnight. And when it did, there was a shift in the power. Probably it had no effect on the normal operation of the 220 system, maybe a momentary blinking of the lights or something but, nothing of consequence. For me it was more than that. At precisely midnight my synthesizers were unpredictable. A key that had generated a particular sound seconds before midnight would generate something different at the moment of the shift, and there was no way of knowing what the change would be. At midnight and for a few seconds after, my synthesizers would surprise me and I had no control over how. I always loved that moment.

We were popular in Amsterdam in those days and the shows at the Paradiso were always sold out but, on stage it was often difficult to tell that. The room was full but, the response was muted. And that was because the audience was so stoned that it took them a while to realize the song was over and by the time they would start to clap, we would be playing something new and once they realized that they would stop to listen. It happened often at the Paradiso that we would finish the show, get very little in the way of a response, leave the stage and climb all the way down to the basement before we heard the applause that then became a wave and we would have to climb all the way back up the stairs to do the encore.

Are you still playing in groups? How do you approach live these days? Do you still need an interaction with an audience or are you happy with studio work?

In June of this year I did a show with Pere Ubu at Le Poisson Rouge down in the Village. It was the first time I had played with the band since 1988 and also the first time I had played live in many years. We had a few hours of rehearsal the day before the gig. I enjoyed that very much, there were two basses a guitar and another synth, no drums. That day the playing was nuanced and textured and there was a lot of space in it… Then came the gig.

An audience changes everything, and not for the better. Musicians tend to get juiced on the adrenaline and they play more often and louder. Most of the nuance and texture were gone. It was not nearly as much fun as the rehearsal.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

Back in 1971 a neighbor had rewired some fuzz-tone units into oscillators and we used to smoke pot and make noise with them through his stereo. Then we figured out a way to hook some colored lights up and manipulate them with dimmers. Then we did a show and people liked it. That was the beginning.

You also play Piano, Theremin, so obviously you are interested in gesture, physical move to create the music so do you prefer to use a keyboard to control? Or patching alternative controllers, for instance to play the envelope generator in a different way having other sources voltage control it?

I have done a lot of experimenting with patching different components together so that one manipulates another.

I don’t play the piano. If you put a gun to my head, I could not play Mary Had a Little Lamb on any instrument. I can create a melody and using software instruments I can move the notes around through various keys, add to it etc. but, it is constructed not played. When I play, everything I do is improvisational. I mainly use a keyboard as a triggering device. I do enjoy the way subtle movements affect electronic instruments.

The EML 200 had no keyboard and I liked it that just putting pressure on an oscillator knob would change the pitch. The Theremin is also very sensitive to movement which I like.

Your compositional process is also based upon the use of acoustic instruments that you process or combine with Electronic.

How do you work to marry that Electronic with your acoustic matiere?

I don’t really work with instruments. I work with sound. One sound suggests another and sometimes when I’m composing I will hear a sound outside the window and realize that it fits with what I’m doing so I go about trying to figure out what instrument makes that sound or how to synthesize that sound. I grew up in a house where there was music. My mother liked classical music and show tunes. My father liked jazz. We had a big console stereo long before any of the families around us did. I still have my father’s record collection which is something over sixty years old now and the vinyl is still in excellent condition.

When did you buy your first system? What was your first module or system?

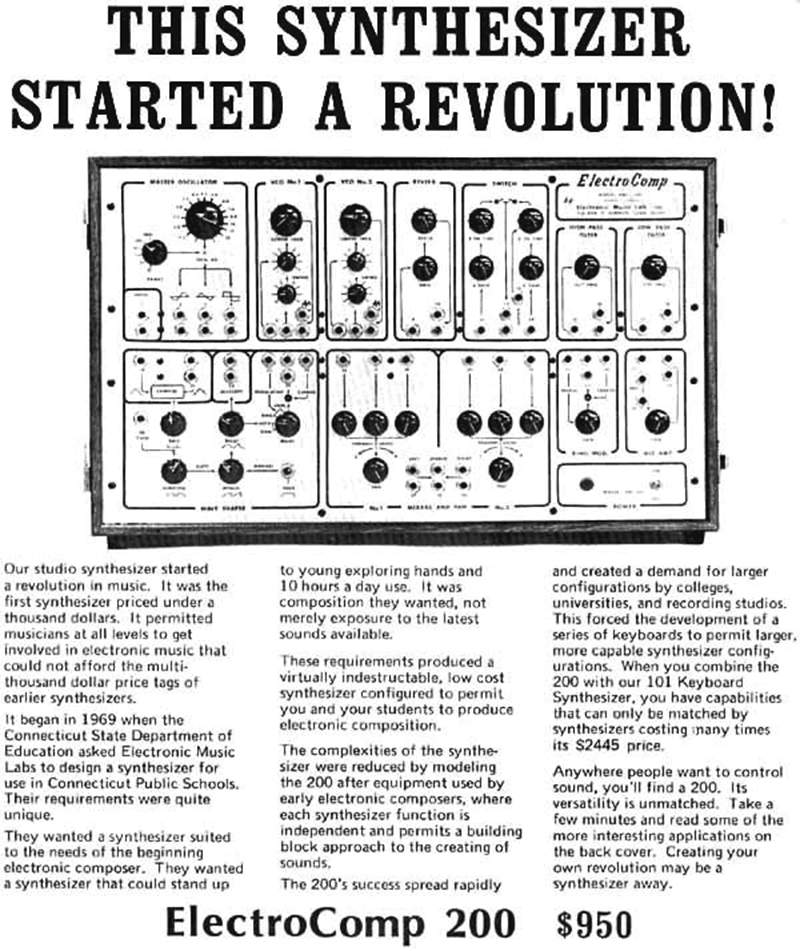

Originally I had fuzz-tones that had been rewired into oscillators by a friend and I had a few of them patched together. Then I came upon an envelope generator and maybe a filter. Someone saw all of it and said there was a thing called a synthesizer that had all of those boxes in one case. I bought one from a company called Electronic Music Laboratories in Vernon Connecticut. They had been contracted by the state to come up with an instrument that could be used to teach electronic music to school children. I still have that EML 200, and use it on occasion. The Williamsburg Afternoon Suites on The 14th Sunday in Ordinary Times have tracks on them that I recorded with that synthesizer in Tony Maimone’s studio in Williamsburg a couple of years ago. And the synth I used at the Ubu gig last June is a miniature version of that same unit made by Electronic Music Works. Neither it nor the original have keyboards and all of the patching is external.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

With Ubu for most of the years I used the EML 200 and also a 101. The 101 had some internal patching and also a keyboard. I patched the units together and used the keyboard mainly as a trigger. For a while I had a patch for each song but, over time I came up with one patch that would cover everything. In the end I came up with a unique patch for each gig and kept no record of any of them. The gig I did recently was also a unique patch and I have no idea what it was now.

I got the 200 in 1972 and I also had a 4 track TEAC recorder. By bouncing the tracks I could get 7 and I would make recordings and then give them away to the modern dance class at Cleveland State University.

The idea of creating things that cannot be duplicated has always appealed to me.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

I compose by starting with a sound and I record almost everything I do. I listen to that sound and ultimately, it will suggest another and so on. I build until I have something and then I start cutting away. I have compared it to making a sculpture but, in my case, I first have to make the rock. Then I find the shape in it and free it.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? You owning an impressive amount of gear, how do you explain that?

I have seven units. And a lot of software instruments. Fortunately, I live in a one bedroom apartment with my wife in Manhattan so space is limited. That works to reign in my desire for more stuff. I just don’t have room for it. When I said I have seven units, I forgot about the 200 and the 101 which I still have but, live in Tony’s studio in Brooklyn and I think or at least I hope, they get used now and then on recordings.

How has your system-instrumentarium been evolving?

I purchased a Haaken Continuum a year or so ago and am bowled over by the depth of possibilities. I bought it because of the multi-axis functionality of the keyboard which I thought suited the way I wished a keyboard would work. I have not been disappointed. Recent works have incorporated it with the EMW 200 as well as the EML 200. A mix of the most sophisticated with the least.

Would you say that their choice of an instrument can be an integral part of your compositional process?

The instruments influence the composition.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

When you contacted me you mentioned that I probably had work that had gone unpublished. That is very true, quite a bit. I work nearly every day. So I went all the way back to the time of making Pharaoh’s Bee. That’s the period that Radio Report comes from. I moved forward from there taking pieces that were made at the time of later works and creating a composition. As I have already mentioned the Williamsburg Suites contain tracks from the EML 200 and the Haaken Continuum.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

I start off with a straight recording, build from there and then edit. I use multiple tracks and have since I began making music.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

All of my playing is improvisational and always has been. After the gig in June the guitar player said to me that it was nice to play with people who knew how to play free. I said it was the only way I knew how to play. That was not a boast, just the truth.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

I’m very happy with the equipment I have. Edward Steichen took a thousand photographs of a white teacup and saucer. I try to remember that when I start thinking that a new piece of equipment will boost my creativity. Instead I need to think of a new way of using things I already have. A new way of looking at the teacup I already own.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Which ones?

I love music and for that reason I don’t listen to it all the time. I spend more time composing than I do listening to other music. When I do listen to other music, I mostly listen to solo piano jazz from the 60s and classical radio.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Start with an oscillator that can create sine, triangle and square waves, an envelope generator, a high filter and a low pass filter. With those components a person can create the tone of any instrument as well as tones that can only be created with synthesis.