Vivants (ALIVE!)

Christophe Modica : Electronics, Sound objects, Modular synthesizer

Zelia Rault : Bassoon, zither, drum, voice

«Vivants» settles into a panorama and weaves interdependencies with it.

This creation explores changes in thinking and practices in our relationships and participation as humans in the living ecosystem. It is based on recorded interviews with people who work the land, plants and animals. It tells a story of what could be relationships other than utilitarian ones, or those built on the dominant-dominated scheme. We gathered the testimonies from those who have already implemented this way of inhabiting the world. But it is told with few words. It is closer to a poem than a narrative. It’s part of the landscape, it’s based on it. Its soundtrack can be at once disconcerting, harmonious, noisy while highly musical. Poetry is created on the spur of the moment, nourished by what’s being played. What remains is the sensation of having shared a suspended, poetic time made up of sounds and voices that have resonated with the place where we find ourselves.

Christophe Modica is a sound creator.

His research is rooted in the porous boundaries between genres and disciplines. He works from reality, then distances himself from it to develop a poetic style that maintains an intimate relationship with life. He questions listening, silence and perception. He is interested in the relationship between sounds, music, landscapes, public spaces, theater and life stories.

He started out as a press photographer, then made a number of documentary films, before devoting himself entirely to sound and music creation in the early 2000s…

Zelia Rault enjoys working with many different styles of music, whether in improvised form, in collaboration with actors, circus performers, dancers or puppeteers.

Her music adapts to the artists she plays with, and the places where she performs. She’s a chameleon for coloring moving bodies, paintbrushes and tightrope walkers. She draws inspiration from journeys past and future.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

My latest works are sound and music creations for interdisciplinary shows with various authors: a public space installation on the transformation of the city and the people who inhabit it, with the KMK company + an itinerant theatrical creation on dreams in which the audience is equipped with headphones. The latter is written by poet Stéphanie Lemonnier.

From time to time, I also work in a trio with a bassoonist and a double bassist on hybrid concerts combining acoustic sounds, electronic sounds and spoken texts.

And then, recently, we created Vivants with Zelia Rault, which is the piece I’m presenting here. We have a number of concerts planned with this creation.Other than those two new projects are also on the go.

One is “À force de douceur”, which I am co-writing with my poet friend Stéphanie Lemonnier. We’ll be creating a poetic concert about the decolonization of the imaginary and the rights of future generations.

And, secondly, « Doxa » with actor-narrator Guillaume Grisel and double bassist Éric Chalan. « Doxa » will take the form of a concert questioning our intimate relationship with the history of the last fifty years.

A number of sound and musical creation commissions for shows are also in the pipeline for 2025.

Do you favor an interaction with an audience or are you happy with studio work?

It’s a difficult question. I don’t want to pit one against the other. I like researching in my studio, circling around an idea, spending hours and hours refining a sound, or a way of patching my synth, looking for what kind of sounds might suit this or that.

But I can’t imagine music without the audience. I always compose, even in the studio, so that it’s playable in public. It’s not always exactly so, but a concert version, played and performed live, is always a variation of the composition I made in the studio.

Listening to music on a support is not the same as listening to it in concert. We’re not the same audience when we listen to recorded music as when we listen to musicians playing in front of us. In fact, we’re not quite the same musicians when we play in a studio or in concert. And we don’t produce the same music. This may not be the case for everyone, but it is for me.

So I don’t favor the studio or live performance. I need both.

« Vivants » is in duo, improvising? How do you approach composition and live these days?

Indeed, « Vivants » is a duo creation. It’s not totally improvised. There’s a lot written down, but it’s not necessarily precise notes or sounds. We’ve created a solid backbone. We know exactly where we’re starting from, where we’re going and all the appointments we can’t miss between departure and arrival. The tensions, moods and states associated with each moment are also written down and determined with precision. The notes and sounds produced, the time we take to move from one state to another, are not written down. They emerge from the situation, our feelings, our relationship with the audience, the venue, etc…

I always compose like that. I’m not attached to the precision of the sound or the note, the speed of execution or the precision of the rhythm. What matters most to me are states of tension, suspension, reverie and so on. I’m also very attached to the harmonic complexities that emerge with the blending of acoustic and electronic sounds. The way we take hold of them to nurture them, sculpt them, let them surprise us.

Once the state we need to be in is written down, all that’s left is to play to get there.

I think for me, composing means creating the architecture, setting the master walls and the number of rooms, determining the volumes, laying the framework. To play is to live, and each inhabitant takes part in the life of the work and its creation.

Zélia Rault: Improvisation was the meeting point between Christophe and myself. During the composition process, improvisation enabled us to research, try out and experiment with ambiances, sounds and textures. As a result, even within the piece’s highly defined structure, there are spaces for improvisation. But these improvisations are also characterized by modes of play, rhythms and moods.

What also strikes me as very interesting about this piece is that we often perform it outdoors. In fact, the place, the audience and the nature around us have a direct influence on our music. The duration can change, a bell or birds can intervene, and we leave room for them.

So « Vivants » is a living piece!

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

The first time I saw and heard a modular synth was at a Radiohead concert in 1998, on the “OK Computer tour ». I was 28 years old. Jonny Greenwood, the band’s guitarist, would sometimes drop his guitar to manipulate cables on a machine as tall as he was. I couldn’t understand what he was doing, but this strange cabinet full of potentiometers produced incredible sounds that he manipulated with great skill. I didn’t even know it was a synthesizer. To me, a synthesizer was a keyboard that produced formless, extremely soft, colorless sounds that lurked in the background of pop music. I hated it!

But there, in that Radiohead concert, I remember being fascinated by both the sounds and the gestures, Jonny’s posture, the way these sounds intertwined with those of the guitar, the bass, the voice…

I didn’t go much further in my research into this instrument after that experience. It was only a few years later, when I went back to studying electroacoustic composition, that I came across modular synthesis. But it wasn’t a very happy encounter. I found the sounds very cold, soulless and lifeless, and I couldn’t get to grips with the machine. It also reminded me of Jean-Michel Jarre, whose music and aesthetics I’ve never liked. So for a long time I composed using sounds that I recorded and then reworked. I quickly got fed up with going through the computer and not having the gestures that are so important to my eyes and those of the audience. So I started to use control surfaces, then DIY instruments that I fitted with contact microphones and worked on live sound via the computer and effects pedals.

When did you buy your first system?

It was only very recently that I really discovered modular synthesis and started equipping myself. After tinkering several times with musician friends who had mastered the instrument, I started to equip myself in 2020. Today, it’s the centerpiece of my set.

How does it marry with your other « compositional tricks »?

Modular synthesis is a natural part of my musical approach. I’ve always been drawn to mixtures, to the complexity and diversity that the complementarity of acoustic and electronic sounds can offer. Today, I continue to use samples, cobbled-together instruments and computerized sound transformations. There’s often a microphone next to my synth to pick up sounds from a cymbal, a cassette recorder, a voice or whatever. I ask myself no questions, I forbid myself nothing.

Modular synthesis has broadened my palette and allows me to put my body to work when I play. It has integrated very easily and naturally into my music. It has certainly dethroned the computer, which is a very good thing.

What was your first module or system?

The first module I wanted to buy was the Morphagene granular sampler from Make Noise.

In fact, it was the first one I bought. It’s quite logical, as I’d been composing from sound recordings. For some time I worked with a small system without a VCO. The Morphagene was the heart of my modular system.

Your compositional process is based upon the use of acoustic instruments that you process or combine with Electronic. How do you work to marry that Electronic with your acoustic matiere?

That’s a question I’m often asked. In reality, it’s all very instinctive. Things aren’t programmed, thought out in detail and then realized. More often than not, they appear while playing, while searching. In such cases, it’s not just the brain that’s in charge, but the whole body that’s at work. Sometimes I have the impression that my hands and gestures are independent, when in reality it’s more complex than that, as the brain continues to do its work. But I believe that all the preparatory work, learning the technique of the machines, the knowledge of the tools, allows things to happen without having to ask how or why.

Afterwards, I can analyze what’s working and what’s not. Often, it’s a question of timbre, resonance and space. Space is very important in my research, and I often try to create depth, distance and proximity. Electronics can also be used to create a kind of abstraction, a discrepancy that I find very poetic. The listener cannot precisely identify the source of the sound. These are tones that don’t often refer to a collective sound memory in the same way as a piano, violin or any other more conventional instrument. Although this is obviously beginning to change, the poetic gap is still there. Complementarity with acoustic instruments makes for writing that is both complex and more meaningful to a shared culture.In this way, the music touches several sensitive areas.

Conventional instruments also bring the performers’ bodies into play in a different way. I also chose acoustic instruments because their timbres, dynamics and tessituras are necessarily in a different space from that of my machines.

Finally, I’d like to say that I like otherness, I like complementarity, I like everything to be possible without any limits or boundaries. I think my music is much better when there are several of us working on it than it would be if I composed it alone. I reject any kind of pyramidal organization; I like imperfection, fragility and porosity.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

I’m not sure I’ll ever finish learning.

It’s only been 5 years since I bought my equipment. My system has grown, but it continues to surprise me all the time. I think it took me about 1 year to start mastering and understanding what could possibly happen when connecting one module to another. Today, I’m comfortable with my system, I can patch knowing what it’s going to produce, I can patch more randomly and let myself be surprised by what’s happening by understanding why it’s happening. This allows me to act on it and make music. But I can’t say I’ve totally mastered this instrument. I’m not sure I want to. I like to play with it rather than play it.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

The effect on my compositional process has been radical. I feel much closer to a sculptor or visual artist than before. I often start from a raw material, a block of sound. It can be a huge block or a very small one. It’s often a small block. Then I add, I dig, I mix with other materials. The meaning, the architecture appears in these first moments of research. I write down my intentions based on the sounds, dynamics and spaces that emerge from this initial work with sound matter. In the beginning, I’d always write down the intention, then look for sounds that could serve my purpose. Today, it’s much more complex. I’m much more involved in dialogue and listening to sounds.

Another very important thing is that I’ve become a performance musician again. I do a lot more concerts and improvisation. I compose things that can be played, that require a performer. I’d started out before acquiring a modular synthesizer, but acquiring and learning these machines enabled me to pass a decisive and important milestone for me: the human relationship, the presence of an audience, composing AND performing.

There’s one thing that took me a while to find. That’s silence. I love working with silence. I even set up a company called Comptoir des Silences (Counter of Silence). But in the beginning, with my modular synthesizer, I made hours of sounds without any silences. It took me a while to get the hang of the machine and work with silence again. Modular synthesis has a fascinating side. It easily takes up all the space, it pulls you along and you can spend a long time following it in wonder. It takes a little time to really enter into conversation with it.

A lot has changed in my life too. First of all, my expenses have increased considerably. Getting a modular synthesizer, especially at the beginning, has a big impact on the family economy. Then it calms down and becomes normal again.

But it brings me a lot of happiness. I spend less time sitting behind a computer. I still play standing up behind my machines. I’ve rediscovered my musician’s gestures. I love the randomness you can have with a modular synth. I have a real relationship with this instrument. In a way, we talk to each other, it suggests things to me, we argue, sometimes it makes decisions and forces me to explore areas where I would never have gone alone. My field of possibilities has opened up enormously.

My instrument also arouses a lot of curiosity at concerts, which makes it a great facilitator of meetings and discussions.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? You owning an impressive amount of gear, how do you explain that?

Indeed, we have a strange relationship with it. But that’s not typical of modularists. Musicians who use pedals, and it’s not just guitarists anymore, also have this particular relationship with their equipment. As far as I’m concerned, I think it’s due to a kind of fascination with tools that can enable me to find new paths and sculpt sounds differently, to surprise myself. There are some modules that really do sound special. Sometimes I can fall in admiration when listening to the sound of a module, just as I can when listening to a sound in the street or landscape. The latter I can eventually record, but most of the time they disappear. I can buy a module and use it whenever I want.

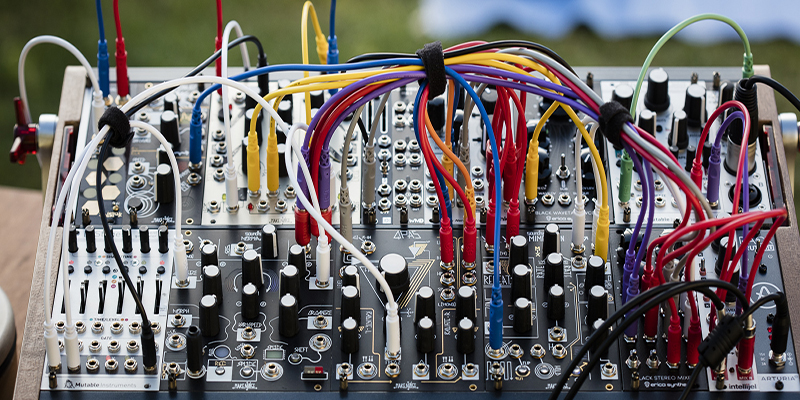

That being said, I don’t have an impressive quantity of modules. I have a 3U plus 1U system in 104 HP that is not full. First of all, I don’t have the finances to buy modules in large quantities. Secondly, there are sounds, music writing and even patching methods that don’t interest me. Before buying anything, I always ask myself how it would benefit my music. How would it make it grow, progress, evolve? I like modules that can be patched in different ways, that can be diverted from their intended uses, modules that can be used for something other than what they were intended for. I often use self-patching and feedback techniques.

But I also know that one more module is often useless. I also like fairly minimalist things, and the constraint of making with what I have at hand is most of the time very productive. Finally, I’m often on the road with my synth, traveling by train. I need systems that can be transported.

Do you prefer single-maker systems or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs?

I don’t know if I really prefer it, but I’ve put together a system with modules from various manufacturers. I think it’s based on different ones that I feel are necessary to go in the directions I want to go. However, there are some manufacturers whose work and philosophy I really like. Modules are not insignificant. They are not simply technical objects that can be replaced at will. They imply ways of playing, patching and composing. That’s what I call a manufacturer’s philosophy. For the most part, however, my system is built around Make Noise + a few from Mutable Instruments.

Almost all my modules are stereo. I have a real obsession with space and depth. Perhaps because of my passion for phonography and listening to the world.

How has your system been evolving?

It evolves according to the needs that arise in my experiments, with the need to diversify possibilities and polyphony. Sometimes, I may buy a module for a very specific need in a project, or to have a version that takes up less space in the box. It’s rare, but – for instance – I recently bought a 6 HP stereo mixing module to replace the 10 HP one I already had, so that I could carry a smaller system on the road.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

Actually, it’s both. But most of the time I choose the modules, because they will enrich my sound palette while remaining in the zone I like. I think there are certain types of sounds and textures that I really enjoy working with and that are always present in my compositions while most Other ones don’t interest me at all.

I’m lucky enough to be able to work as an artist, making the music I want to make. I don’t respond to commissions that would require me to go for types of sound that I don’t really like.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

I work a lot with hybrid systems. But until now, I’ve never used effects pedals or the like. I use dictaphones, small percussion instruments, finger pianos and odds and ends fitted with contact microphones. I often use microphones that fit into my modular system via the Joranalogue RX2 module. Then I play with these recordings. It’s a sound source, like the Morphagene or a VCO.

Sometimes, I also use computer tools and real-time sound processing. This is particularly true of my bricolages fitted with contact microphones. But I use them as an autonomous system in parallel. Like a second instrument.

I also use computers to read audio files such as interview voices or phonography, which I really enjoy working with.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

For this creation, entitled « Vivants », I’m using two systems in parallel. One is a computer system that triggers voice samples and other sounds, previously created with my modular system, which I assign to a sampler via a midi keyboard.

I also use this computer tool to play and transform live sounds from a board to which I’ve attached nails, toothpicks, music boxes and other odds and ends. It’s equipped with a contact microphone that fits into the sound card.

There’s also a microphone that fits into the sound card and allows me to work on my voice, a finger piano and the manipulation of two pebbles.

Added to this are the sounds I produce with my modular system. Essentially, I use the Morphagene, the Mimeophon, the XPO from Make Noise, the Black Wave Table VCO from Erica Synth, two stereo filters: Make Noise’s QPASS and Shakmat’s Dual Dagger. I also use the BEADS and STAGES modules from Mutables Instruments and Maths from Make Noise. There are, of course, a few envelopes and a Low Pass Gate.

Then there’s Zelia, who plays the bassoon, the shamanic drum, her voice and a cythar. Sometimes I record the sounds she produces and send them to BEADS.

That’s a lot of sound sources to play with. The computer tool also enables us to manage spatialization. In its concert version, « Vivants » is played in multiphonic mode. There are 4 loudspeakers around the audience, 1 central loudspeaker at the front, and 2 100V loudspeakers broadcasting only mid-range frequencies, placed as far away as possible depending on the venue. The computer tool then manages the distribution of sounds in space and their movements.

For the whole computer part, I’ve been using a software program for a long time that I really like and which is very efficient: Usine Hollyhock from Sensomusic.

I really like this type of highly hybrid set, in which everything is interconnected and interrelated.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

I think you’ve already figured it out, but I don’t have any rules that I respect 100%. I hate dogmas!

Most of the time, I record live and I don’t overdub. I compose, work with my set, rehearse until my performance is as acceptable to me as possible, and then I record. I often record in multitrack so that I can mix afterwards. In other words, I’ll equalize, play with volumes and maybe add a little compression.

I also sometimes shorten certain passages that I find too long once I’ve taken a step back.

But sometimes I’ll add a few tracks, especially samples that I can play live later.

Having said that, I can sometimes make multiple overdubs and arrangements on the computer and then find a way of making them playable live. But that’s not what I prefer. I don’t really have any rules, and it depends a lot on the project. If it’s a recorded music project that’s not intended to be performed, I’m going to intervene a lot more after the recording.

Everything is possible, and I try not to restrict myself in any way.

« Vivants » is a live recording. We did very few takes and no editing. I chose the best take and accepted its imperfections. I only did a little editing to remove a few extraneous noises and some mixing.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

It depends on the project.

« Vivants » is very much scored and my system needs be pre-patched. For other projects, that’s not the case. But most of the time, especially on composed music, I have at least a starting patch and some specific patch notes on a piece of paper for certain parts.

Which module could you not do without, or which module do you you use the most in every patch?

Once again a tough question. And I think, in reality, that I can do without any of them and still manage to make music and enjoy myself. It’s something I do a lot. I only use one module to produce sound, and eventually add an envelope or a modulator and a Low Pass Gate. No VCA.

But if I had to keep one only, I’d probably say the Morphagene. I also love the Mimeophon, it’s an incredible module with some pretty crazy possibilities

Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

No, never.

I’ve tried a few VSTi, but I’ve never been convinced.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

How about that!

I have no idea.

I don’t dream of any particular system. I dream of music, of sounds, of compositions, of sonorous or dissonant harmonic relationships, of spaces in which sounds evolve, of relationships between musicians, of relationships with an audience…I dream of a less stupid, less mercantile and less futile humanity, I dream of otherness, equality and attention to others, but I don’t dream of any system or module.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

The pleasure of patching !!!

Deciding in a fraction of a second which cable I’m going to grab, what length, what color, what connection I’m going to make between my modules. Then being surprised by what happens and having to react again.

BE IN CONVERSATION WITH YOUR INSTRUMENT.

Not playing a synth, but playing with THIS modular synth that’s here in front of me.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Which ones?

In fact, I don’t know many of them, and the few I have met only talk to me about technique and modules. The only one with whom I have a very friendly and musical relationship is you, Philippe.

And I love your music. I’ve really enjoyed your latest pieces, especially the ones with the piano and «Dementia» (Session 114).

I don’t know her personally, but Sarah Belle Reid’s musical approach interests me.

There are a lot of musicians I feel close to, even if they don’t play a modular instrument.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

All the people who experiment freely inspire me a lot.

I must admit that people like Don Buchla or Serge Tcherepnin are very inspiring. They’ve enabled so many things to become possible. They helped to make the world a freer place by allowing music to move out of its comfort zone.This is also true of electroacoustic pioneers such as Bernard Parmeggiani, Luc Ferrari and many others, as well as composers like John Cage, György Ligetti, Éric Satie, Karlheinz Stockhausen and many others…

All these pioneers opened doors, created possibilities, made music more democratic, less capitalist. This is still the case today; there are always pioneers. When I came across the work of these people in my life as a musician, I was immediately aware of the immense freedom that music could offer.

For me, that’s the key word for this kind of music: FREEDOM!!!

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

It’s not as complicated as it sounds. It takes time, research and experimentation, but the pleasure comes very quickly. It’s fun, and it lets you produce really beautiful, and warm sounds.

Choose your first modules carefully. It’s not a question of quality, but of sound and playing style. Ask yourself if you need great precision or if you’re more attracted by more slobbery sounds. If you want modules that could surprise you or may reassure you.

Before you buy, ask yourself where you want to go. All paths are good, but they don’t require the same tools.

Don’t ask yourself too many questions either. Modules sell very well, and the second-hand market is very active.

An initial investment of €2,000 seems reasonable. You’ll still need a few modules to enjoy yourself, and a powered box. A 104 HP box will seem large at first, but a smaller one will probably be quickly resold for a larger one.

I don’t think it’s possible to anticipate how much fun you’ll have with a machine like this. But believe me, it’s enormous.

I know that there are multinationals that make copies of modules at extremely low prices. If you can avoid it, please do. They are bandits who plunder the work of others. Most manufacturers are small companies of enthusiasts who do wonderful work. Send them an e-mail and they’ll get back to you promptly and honestly. They take great care in their work and produce high-quality modules. This is not the case with multinationals, who will never promote creative freedom. Sometimes, it’s not just a question of money.

«Vivants» was created in 2022 and made possible by:

L’Atelline, lieu d’activation art & espace public (34)

Superstrat (42)

Lieux Publics, centre national & pôle européen de création pour l’espace public (13)

Le Portail Coucou, café-concert (13)

La Chouette, association culturelle du territoire Alpes Provence Verdon (04)