John Mills-Cockell (b. 19 May, 1943 in Toronto, Ontario) is a Canadian composer and multi-instrumentalist, perhaps best known for his ground-breaking work with progressive / avant garde groups Intersystems and Syrinx, and for his numerous works for radio, television, film, ballet, and stage.

Mills-Cockell was one of the earliest adopters of the Moog synthesizer, and is generally regarded as a pioneer in the field of electronic music.

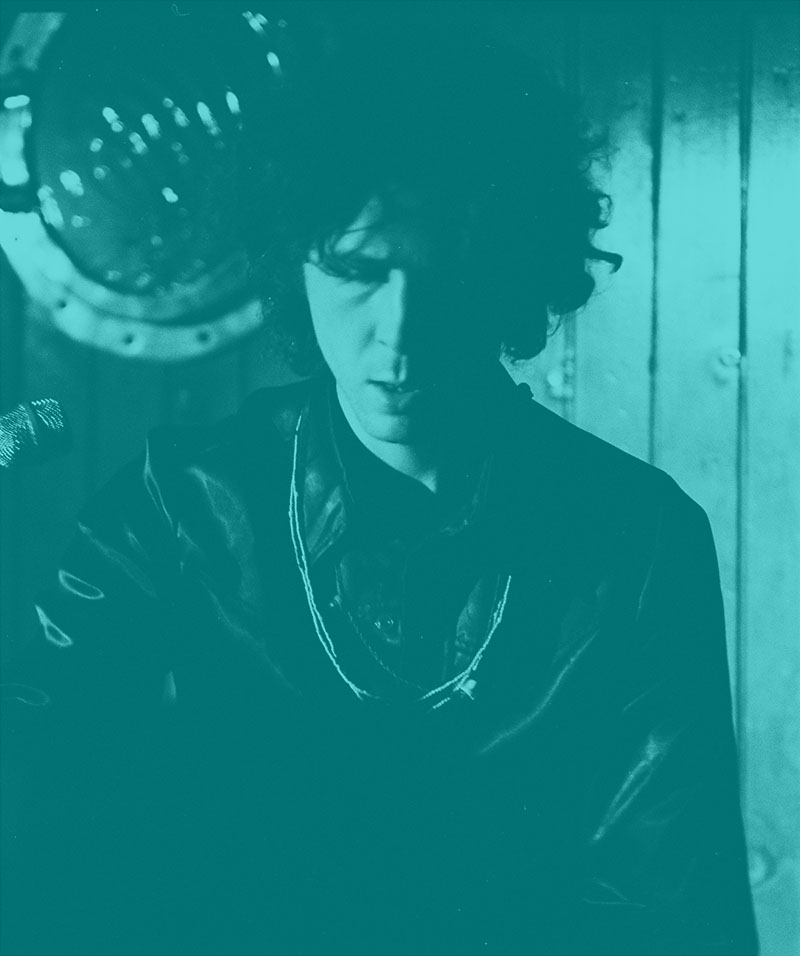

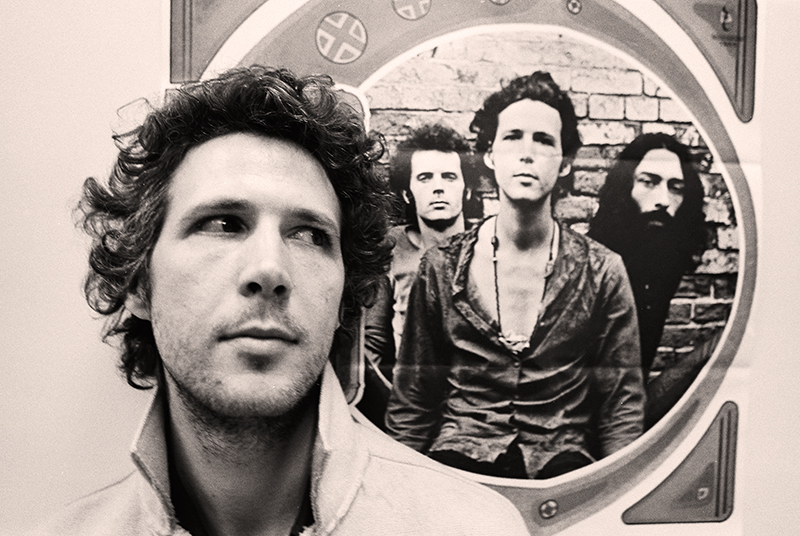

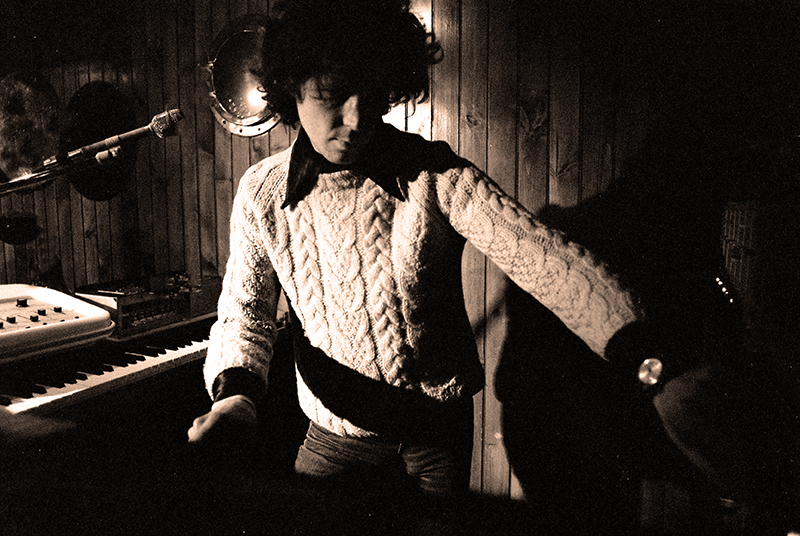

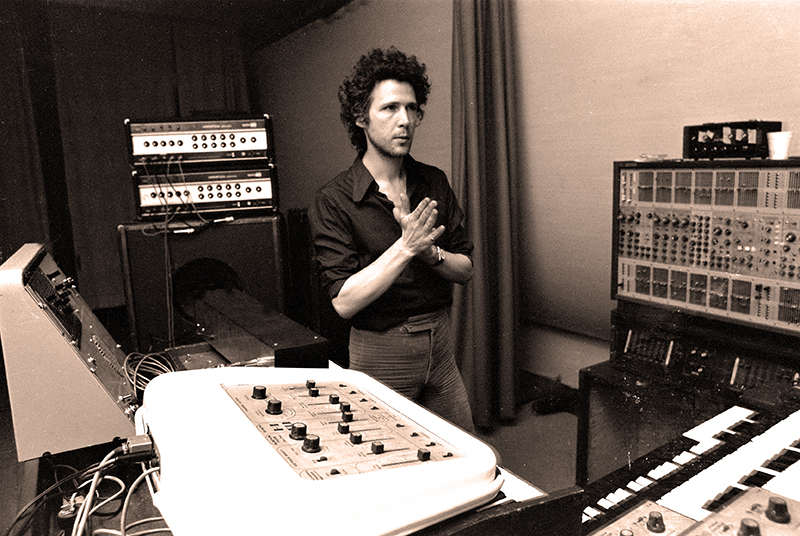

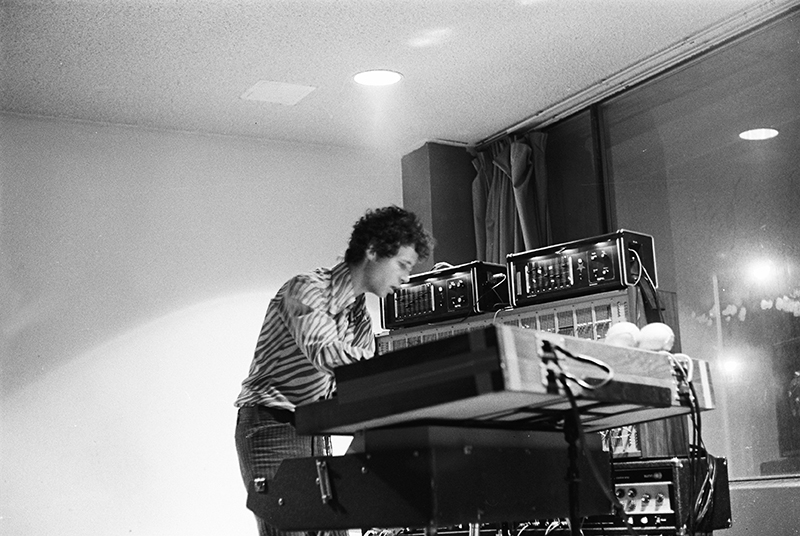

Pictures of JMC are by Arthur Usherson.

We are proud to offer 2 works that had remained unknown ever since they were recorded back in the late Sixties…

You have been pioneering in Modular Synthesis and Intersystems has been active for years, would you please retrace your career?

My interest in electronic music began some years before Intersystems formed. I was 15 when I heard Hugh Lecaine’s « Dripsody ». Another seminal experience was in 2nd year Bachelor of Music when Stockhausen presented his 4 channel performance of « Kontakte » for 4 Loudspeakers in Walter Hall, Edward Johnson Bldg.

In the late 60s I began studies composition with Dr. Dolin & piano with John Coveart, my 3rd year into the Bachelor of Music course at University of Toronto, I began composition studies with Dr. Samuel Dolin & piano with John Covert. Composer Ann Southam was also Dolin’s student. Under Dr. Dolin we taught electronic music in Dolin’s small electronic studio in the basement of The Royal Conservatory of Music. It was a pay-as- you-go course in electronic music, the first of its kind!

In the first class there were 12 ‘students’. There I met sculptor Michael Hayden, poet Blake Parker, & architectural designer Dick Zander.

The four of us became the nucleus of Intersystems whose first project was Michael Hayden’s « Perception 67 ». One of the features was a series of 10 rooms simulating 10 psychedelic experiences using fanciful projections, with various tactile, olfactory and sonic experiences that attracted writers & photographers from many of Canada’s significant publications all raving over the controversial artwork that included my electronic music with recordings of Parker’s poetry. The ‘trip’ was a first-of-its-kind artwork experience, somewhat related to happennings. It attracted much press and the publicity provided us with enough renown that we were encouraged to form ‘Intersystems’ with the objective of creating art works that incorporated our interests and training in multimedia ‘presentations’.

This was in fall 1967. We set up a studio on the 2nd floor of a converted egg processing plant with room for each of the 4 of us to have our own space. After a year of making ‘presentations in Toronto, New York, Kingston, London ON etc, we were able to acquire an exciting new musical instrument named the Moog Synthesizer: a technological breakthrough that could be programmed to make any sounds we imagined. With 2 trips to Trumansburg, NY where the Moog ‘factory’ was located we raised money purchase this amazing newly developed modular synthesizer of Robert Moog. Although musicians were building electronic instruments that combined electronics in various ways, until then we were using handmade, improvised ‘instruments’ that we incorporated with Parker’s spoken, declaimed poetry into semi-improvised sound pieces. Robert Moog’s ‘electronic music synthesizer’ was one of a very few that became available that were unified modules to be played somewhat like conventional instruments with music keyboards suitable for musical performance. Like many other artists, I was thrilled with the potential. It was exciting to ‘patch’ together various modules to make newly ‘invented’ sounds previously unheard for musical expression performed via a music keyboard.

The new synthesizers came in various ‘models’, each utilizing different ways to combine and perform the various modules. I was immediately drawn to the Moog design because it came with a piano – like keyboard to produce & play the sounds while others were designed for other means of making synth sounds.

Each in its own way was liberating.

From your point of view as a pioneer, is there anything left to invent in music? Do you think that it’s important to try and innovate, or should the priority be simply to play music, to have pleasure while creating?

It was important for me and my Intersystems partners to be able to create previously unheard sounds in combination (compositions, or improvisations).

In these early days it was fun & exciting! Still is…

Well . . . yes & no: Gould played Bach’s 2 & 3 Part Inventions on piano? Lizst’s Preludes, getting a little pretentious? But that raises questions about all kinds of music.

I often think that in the 60s, and into the 70s, when electronic music was still in its infancy, at least for those like me who are not academics, anything seemed possible. You can sense in the creative work of that “Age of Aquarius” that composers let themselves be surprised by the new. It seemed possible in those days? It was still possible. And it was fun! Actually, even now it’s fun!

Then, in the 80s, for some a certain notion of control emerged, a desire for audio synthesis that would allow the instruments of the orchestra & other disciplines to be remade (rediscovered). How dd you feel about that?

This was exciting because I could pretend that with some rudimentary knowledge gained via my Bachelor of Music studies, that I was able to play a few instruments. I learned piano since I was 4, was in choir since I was 5 and learned then to read anthems with music notation before we did it at day school. With a little pedagogical guidance one might quickly learn rudiments on a number of instruments. I played bassoon in high school & violin at University of Toronto. Violin & choral singing were courses in my first year B of M. One learns simply to pick up an instrument & play with it until it feels & sounds like it is musically ‘satisfying’. Working with an accomplished instrumentalist is always helpful. My father was a violinist.

Outside of the conservatory of course jazz: Ellington, Bud Powell, Monk, Trane, Ornette were essentials too). Another dropout friend, Arthur Charpentier was an organist who introduced me to Olivier Messiaen. None of these were exponents of electronic music, except of course for those rare opportunities to hear & see these masters live , in person, their (recorded) music was electronic too!

One of my greatest experiences was meeting Miles after our onstage set at Massey Hall. He was waiting to enter the stage for his set: « Witches Brew! » And then Ravi Shankar asked us to play after his set in Montréal Place des Arts so as not to desensitize his audience’s ears. We were booked as such, but really, in world music, indeed, ‘electronic’ music, Ravi Shankar was master of his art!

How can one avoid losing the spontaneity that the analogue instrument allows and that so many composers have lost since they do everything from their computer? The click of the mouse doesn’t sound like the turn of a knob, does it?

In my admittedly limited experience the click of a mouse can be redefined with one’s computer in a huge variety of creative ways: up down, sideways, faster, slower, etc. Fair enough, it is not really the click itself. The click simply initiates whatever gesture it is programmed to do. In the 80’s digital synthesis became more available, even in conventional music stores. The expressive range for instrumentalists & composers became so much wider. This meant that musicians could more easily emulate sounds of conventional instruments, using electronic instruments. The theremin was one, but then with somewhat more advanced technology the Wurlitzer Electric Stage Piano, the Yamaha DX-7 was the most first popular digitally programmable electronic instrument, then the Prophet V which played recorded samples, & the Roland sample players, & the Yamaha Q-80 (one of the first digital sequencers). The floodgates were opening! A wider variety of musical gestures became easier to execute electronically (volume, glissandi, vibrato) etc. As we all know now, the evolution of both analog, digital instruments & controllers fills entire libraries. All through the digital evolution, analog modulars were also attracting many users.

What have you been working on lately? What do you usually start with when composing?

I have been doing all of the above! In particular I am constantly seeking ‘new’ sounds coupled with new ways of ‘musical’ expression, created by means of modular synthesis and now ‘post modulars’. They incorporate various modular design features, with often more compactly integrated design. I know that I was cheating myself (& others) by not continuing to explore the possibilities of all the instruments in my studio & elsewhere: newly developed instruments, & sound sources not previously acknowledged, especially new ways of thinking (& hearing). Recording musical instruments and natural sounds have also evolved through the evolution of many integrated designs using more sophisticated audio generators & processors. That said, the simple patching we used in Dr. Ciamaga’s classes are the basis of a great many of the electronic instruments still in use today. Nowadays there is a proliferation of variations on a great many instruments, including keyboard instruments of many different divisions of musical scales which musicians are beginning to learn & incorporate into their compositions.At the same time however, I was fascinated with various avant-garde music composition techniques.

How do you see the relationship between sound and composition?

When I first started: just married, living in the 3rd storey of an old brick building across the street from Knox Presbyterian ‘Cathedral’ at southwest corner of Spadina & Harbord in Toronto. I was studying composition with Dr. Samuel Dolin at the Royal Conservatory, newly located at Bloor & Avenue Rd. My piano teacher was John Coveart. There were appealing & appalling sounds of all kinds emanating from the building’s windows onto the newly moved Faculty of Music on Philosophers’ Walk. And from my Spadina aerie were TTC streetcars, their metallic wheels squealing as they turned onto Harbord, honking trucks, sea gulls squawking.

I hung 2 mics lent to me by Saul Mendelsohn, then owner of Bay Bloor Radio out my window. Bells chimed from St. Andrew’s Cathedral, car horns, people laughing, organ sounds on Sunday mornings. I recorded it all on one or both of my 2 track tape decks.

How strictly do you separate improvising and composing?

For me even now, each case is different. If I know who will be performing, under which circumstances, & when (tomorrow or years later), may determine how much the piece is improvised or not. If the piece is a song with fixed text, that may determine whether the music is specifically notated, although certainly not always. Many composers like to use various kinds of pictorial scores for performers to use as guides for what they play or sing. In such cases the composer’s concern can be simply the dynamic shape of the piece and perhaps an idea. Sometimes composers’ works determine the instruments used.

I often like modular instruments and ‘acoustic’ instruments together, determined by the sonic nature of a piece, not necessarily predetermined in the score, but rather by the instincts of the performers. Anyway, I digress. Personally, I mostly have taken on a much more specific, active role, to achieve a particular aural/musical outcome. Years ago I was so fascinated by modulars that I composed pieces using exclusively modulars. However currently, once again I consider creation of works which are less restricted. In this case, how is chaos possibly a determinant in the final nature of the performance of such a musical work? Of course I’m not alone. We were working with new ways of making noise! Undoubtedly the use & design of modular synthesizers play a significant role for many. What is the philosophy ‘guiding’ a particular work?

I have stuck primarily to performances with a specific goal in mind, through the use of much more specific musical techniques in achieving specific musical ends, but needless to say the instincts of performers themselves very often shape the outcome. The ends result from all kinds of specific goals (needs?) be they rational, practical, emotional.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

This depends on a number of factors!

Does a ‘composition’ require more, musically speaking, than the musicians (or engineers?) on hand can provide. Does the composer think of something (an additional sonic element) than was imagined post session? Does the performance of some one in the ensemble, heaven forbid, not work out as initially expected? The fact that I play keyboards makes my choice of keys frequently my go-to. Moreover keys come in many types, stripes & colours! And these days sample collections are often very well programmed & recorded. They come in an incredible variety, possibly filling a need for instruments not readily available.

How do you deal with your desire for classicism?

I’m still discovering, pivoting between jazz, pop, ‘folk’, blues, and what we call classical: any of those ways of hearing: performing with our bodies, with our hearts. Was Muddy Waters not classical?

If by classicism we mean recognizable forms, consummately performed, I think that was the case. The reason for it is obvious: we were able to make music that was somewhat s stylistically familiar. The sounds of musical gestures have ever been evolving. Electronic music was inevitable, evolving ever since we could generate & make sounds by controlling electrical energy.

What type of instrument do you prefer to play?

This is usually dependent on the demands of the particular piece.

Keyboard instruments are most often my first choice, but I have done a lot of work with microphone (or DI) recording when it is thought that the addition of another musician’s ‘character’ or proficiency may add to the piece; only steel guitar players can play steel guitars >:} Or sometimes manipulating the recorded sounds in various ways is introduced into the work in order to add another, different musical quality. Many composers have a particular keyboard they like to use. And/or nowadays many composers & sidemen record albums with specific sample libraries to emulate various instrumental ensembles.How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis?

I first heard electronic music when I was fifteen In Royal Albert Hall. It was sort of an accident.

When did that happen? As mentioned above I first encountered modulars (sort of) in Hugh LeCaine’s studio in Ottawa.

I & Syrinx, were playing at Le Hibou in 1971, just around the corner. LeCaine’s instrument was called the Sackbut. It was still in development! In fact by this time modulars were popping up ‘everywhere’. LeCaine’s instrument was different in that conceptually it was part modular, and more like the part The modular that stands out for me is the SynthesizerDotCom setup, because, for the quality engineering and it was for me affordable. As it is, producer William Blakeney helped me choose the modules. I have recorded & com- posed many works with this array of modular instruments. Many composers can’t help comparing the SynthDotCom’s with the classic’ Moog’s, but most comment that the Moog has superior sound. I’m not quite as fussy simply because there were many: dancers, theatre directors, rock bands, television producers who loved the sounds and I must say, the availability of electronic music, unlike anything heard before as well as recognizable ‘music’ if needed, emanating from these exciting new sound generators AND daring new artists.

When did you buy your first system? What was your first module or system?

This purchase was made in February, 1968.

I was accompanied by Intersystems cohort Michael Hayden. We picked it up at Robert Moog’s ‘factory’ in Trumansburg, NY.

This was our first modular.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process? On your existence?

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

Probably a few days.

How has your system-instrumentarium been evolving throughout the decades?

The system that we acquired was relatively ‘complete’.

As I recall, a 2nd sequencer would have been very useful. We bought one a few months later. Also it would have been useful to have a voltage controller over each of the frequencies on the Fixed Frequency Bank.

But honestly, interesting, useful additions could always be made, but so much can be done with the assortment of modules packed into the 100 spaces that I now have. There are now an additional 2 satellites with 4 modules each which we acquired about 9 months afterward.

Would you say that your choice of instrument is an integral part of your compositional process?

Not really.

There’s no doubt that buying another make of synthesizer would inevitably lead to exploration of sounds & gestures not available with this instrument. However I don’t think that I would like to commit all my time to composing with only electronic synthesizers. The world of music has so much else to offer!

My system is “synthesizers dot com”, quite similar to Moog Mark II.

« Psychedelic Poster » dates back from 1968. « Light Compression » was recorded in 1969.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music? What did you have in mind? On which occasion were they played?

I performed « Psychedelic Poster » in 1968, at The Ontario Art Gallery, soon after Intersystems acquired the Moog Mark VI, in Trumansburg. That was the only instrument (modular synth) used in those two improvisations.

The existence of « Light Compression » only came to our knowledge last year (2024). At that time the recordings were two untitled solo improvisations, subsequently titled and produced by William Blakeney.

It was sent to Blakeney by Californian musician/artist/historian Tom Recchion.

Did you record straight with no overdubbing, or did you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

There was no overdubbing, the two pieces were recorded live, solo.

Which pioneers influenced you and why?

Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage!

I remember that Walter Carlos & I took delivery of our Mark II’s on the same day in early February. Intersystems’ first Presentation was 3 or 4 weeks following. « Switched on Bach » was released maybe a month later.

How was the scene in Canada back then? Were you friend with Phillip Werren or The Canadian Electronic Ensemble for instance?

I knew of The Canadian Electronic Ensemble, but did not meet any of them.

I heard them on CBC Radio’s 2 New Hours. I attended concerts by Michael Snow with his bandmates, although I do not recall that modulars were played backthen.

I was really in a different world: attended jazz clubs of the day, the First Floor Club, George’s Spaghetti House; we played at Colonial Tavern, Gaslight Upstairs etc. I first encountered modular synthesizers in ‘real life’ at Dr. Moog’s ‘factory’ in Trumansburg, NY, 1967 and I met Walter Carlos when he was taking delivery of his new Moog, as were we, Intersystems.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their Modulisme skills?

Patience when working with new modules.

Have fun!