Daniel McKemie is a composer, percussionist, electronic musician, researcher, and arranger based in New York City.

His current work includes using techniques rooted in Music Information Retrieval to develop new sound palettes and approaches to audio processing. He also focuses on utilizing the internet and browser technology to realize a more accessible platform for multimedia art.

His music has been performed in Europe, Asia, South America, and Australia; and his research on computer music and web-based audio/composition techniques has been presented and published internationally in conferences such as the Korean Electro-acoustic Music Society, the Australasian Computer Music Association, the International Symposium on Computer Music Multidisciplinary Research, the Society of Electro-acoustic Music in the United States (SEAMUS), and Percussive Arts Society International Convention (PASIC), among others.

I don’t typically share my personal feelings explicitly through art or attach empty meanings for the sake of “programmatic music.” However, in this instance, these pieces reflect a profoundly emotional period in my life. Throughout the conception, creation, recording, and finalizing of these works, my wife Sarah was battling cancer, to which she ultimately succumbed to in the spring of 2024.

Music was my sanctuary.

Theia Mania embodies what the Greeks called “divine madness”, the sensation one might feel experiencing love at first sight.

Slaydie’s Knees isn’t a sequel but a tribute to earlier works created when I first met her. This series blended MRI recordings with synthesizers in a call-and-response format. Her suggestion to listen to MRI machines came from scans on her injured leg from roller derby, unaware at the time that such machines would later become routine in her cancer treatments. The piece doesn’t include recordings or samples from these machines, as there are no more scans to be had.

This Session is wholly dedicated to Sarah Marie McKemie, whose love and admiration transformed me in immeasurable ways.

I will forever miss you.

Coda (2024)

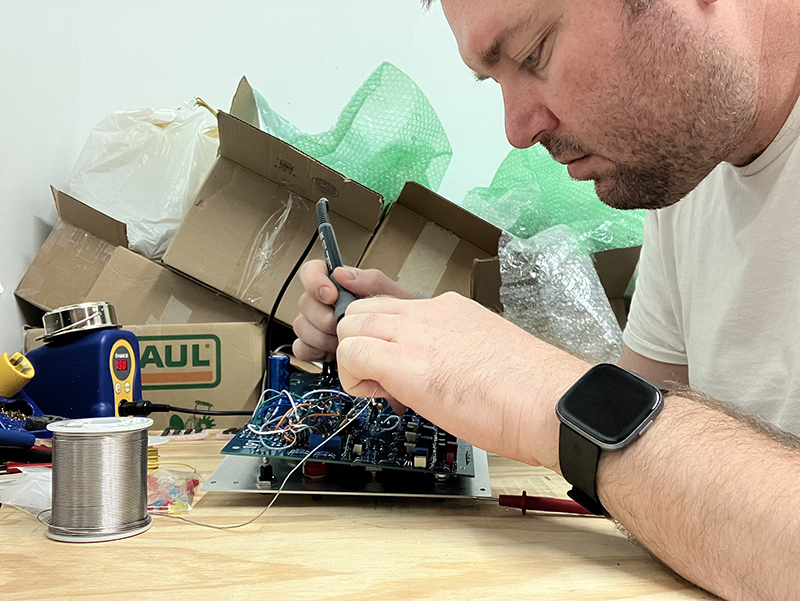

While seemingly out of place in the track order, Coda is the first work I wrote taking a new approach of slowing things down in my process while more deeply exploring the aesthetics and creative goals outlined in these notes. Having moved all my equipment back home from my studio, it is an area that forces me to do all performing, recording, sampling, and effects processing on analog hardware. The purpose of this is not around gear fetishization, but instead to really examine the fundamentals of effects processing, synthesis, mixing, editing and listening. It’s also a love letter.

Lower Springs (2009)

This was one of the first works I composed as a graduate student at Mills College, in James Fei’s Electronic Arts course. The class assignments were designed to explore topics in aesthetics, such as process art, sound art, mixed media, video, and film. Lower Springs was originally written for a video piece, which was eventually scrapped, leaving only the music. I found some inductor mics in the Prieto Lab, where the class was held, and began exploring the sounds of electromagnetic fields from devices around my studio. The technical setup was intentionally kept simple to focus on the audio itself, routing it through a mixer, recording onto 1/4″ tape, then remixing, splicing, and bouncing onto a second tape machine, resulting in the final work.

Metals (2008)

While I had been writing, performing, and releasing music under different monikers for a few years by this point, this is my first serious composition. Originally conceived for percussion and tape, the concept revolves around the acoustic and electronic manipulation of resonant metals. The piece was recorded, processed, and mixed on a Fostex MR-8 Digital Multitrack Recorder—a rather tedious device with uninspiring effects. The acoustic elements are more prominently featured, as I was far more comfortable with these than with electronic ones. Cymbals, gongs, tam-tams, homemade devices, and crotales were bowed, struck, and rolled; submerged in water; taped in parts to isolate harmonics; played against an open piano; on timpani with the pedal bending the pitch, and more. The goal was to capture all these sounds with the portable recorder and build a tape part to accompany a live score, but as the music reached a certain level of completeness, it remained solely as a fixed media work.

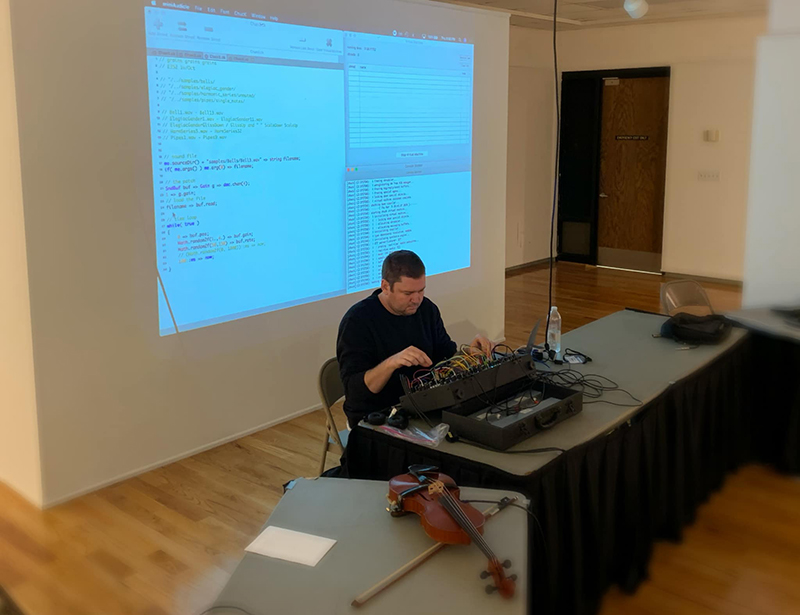

Decontrol for live electronics and audience (2020/2022)

Originally written for live-stream performances during the COVID lockdown, I adapted this piece for the concert hall at the 2022 New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival. The audience is invited to visit a web page that allows them to directly control the soloist’s instrument. This page features an interface with sliders and buttons that transmits high-resolution, 14-bit MIDI data via WebSockets to the performer’s computer. The data is then converted into control voltage signals, which are sent to various points in a modular synthesizer and other handmade circuitry, effectively inviting the audience on stage to turn the knobs themselves. The performer has no prior knowledge of how the audience will interact with the web page, what information it will transmit, or when the transmission will occur.

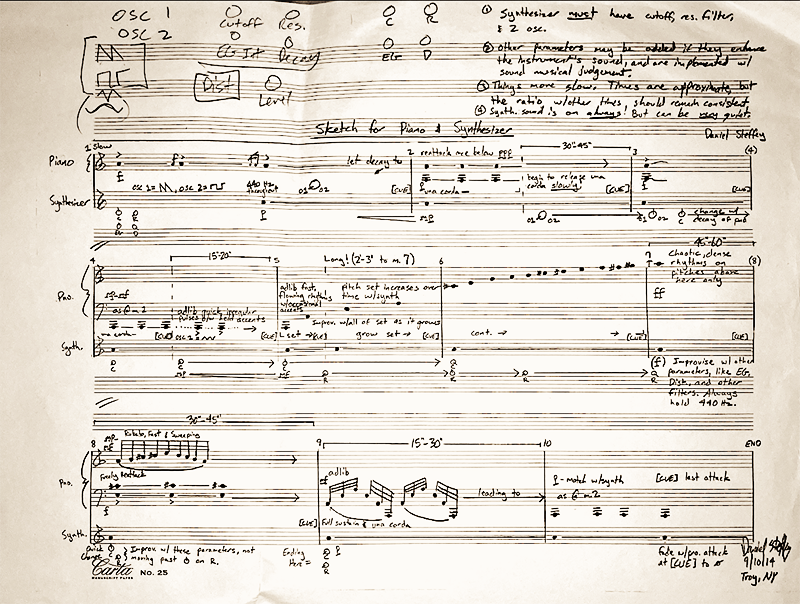

Zen in the Spectral Key of A (2012)

This was my first attempt at combining acoustic and electronic elements in a notated composition. Heavily inspired by the work of James Tenney, I aimed to create a space where electronics could interact with an instrument without any live processing. This idea emerged when Ryan Ross Smith and I were recording several of his animated scores in upstate New York. After a break in the day’s work, I shared this score, and we discussed ways to bring the piece to life. There was a racked Moog Voyager, without a keyboard, and we proceeded with rehearsing and recording. For me, the significance of Zen was that it successfully conveyed the notated work for live electronics I had envisioned, with minimal discussion and planning needed from the performers. Over the years, various approaches to live electronics notation have been used, from listening scores to texts to graphics. I remain deeply interested in exploring the tension between the openness of electronic instruments and software and a system of musical notation to achieve compositional results while preserving the performer’s voice. The work in Zen laid the groundwork for my radio opera Pneuma, which premiered at Wave Farm in 2014.

Theia Mania Mvts II & III

Floating Feet (2023) / Slaydie’s Knees – Part Infinity (2024)

Theia Mania is a three-movement collection written between 2022 and 2024, consisting of Sample Systems, Floating Feet, and Slaydie’s Knees – Part Infinity.

Though not the only music I composed during this time, these works share a common focus on aesthetics, with no technical goals or experiments in mind. After nearly six years of immersing myself in Web Audio, I needed to set aside technical aspirations and reconnect with my foundational musical instincts.

You are based in NY, how is the scene there? Would you tell us more about your surroundings? Composers you like, feel close to?

I’ve been in Brooklyn for nearly nine years, and I love it here. I always tell people that you can find at least a dozen others in the city who share any niche interest you can think of. There are several venues all over the city, some great underground and DIY spots, many well-run and professional ones, and they treat performers well. Others don’t! But that’s the case anywhere.

I haven’t really latched onto any one scene or style. Since moving here, I’ve found myself attending more art shows and galleries than concerts. I love the freedom of moving through a space and discussing ideas and aesthetics with creative people working in different mediums as it’s all so transferable. I do try to make it to concerts where I don’t know anyone on the bill but have some idea of the music. It can be tricky, though, because venues here don’t often specialize in a single type of music; the lineup can change completely from night to night, or even within the same day! A club might host a lecture meetup in the afternoon, punk bands at 7 p.m., and then transform into an all-night rave by midnight.

After doing this for so many years, you notice how people take different paths. Some move on to things outside of music, others experience meteoric rises and become incredibly famous, and many fall somewhere in between just working, practicing, and showing up day after day. I find that I’m most influenced by people I personally know or collaborate with, and there’s no shortage of them in the city. The live coding scene is booming here, and while I don’t participate in it, the DIY and community-driven ethic of that group is incredibly inspiring.

One person who stands out in that scene is Melody Loveless, whose music and teaching seamlessly integrate technology, performance, and aesthetics like no one else I know. Ryan Ross Smith, a dear friend and frequent collaborator, amazes me constantly with his staggering volume of musical output spanning multiple genres. Since diving back into academia, I’ve met more inspiring figures there as well. Luke DuBois always delivers an engaging and unpredictable show, flawlessly executed every time. And then there’s Eri King and Daniel Greer, who work together as Eridan, blending visual and mixed-media art with music in a way that epitomizes creativity, no matter the medium.

Bringing it back to visual arts and galleries, this is why I’m drawn to those spaces. Practice is practice. Whether we’re playing synths or violin, painting, or drawing, we’re all honing our craft. Having been immersed in music for nearly 30 years in so many roles, I’ve developed an ear for recognizing the practice behind the finished piece. And that’s what makes NYC’s endless variety so thrilling is that the artistry here is a reflection of relentless, passionate work in every form.

Your artistic practice covers many different mediums and aesthetics, and you were fortunate to study with Morton Subotnick in the fall of 2022. Would you develop on that?

What did he teach you, and how did it influence the way you compose? What subjects have stayed with you and influenced your practice?

I was incredibly fortunate to study with Mort, and the latest pieces on this record are a result of new approaches picked up in these lessons. His lectures often centered around a core question: “If everyone has access to the same technology: software, hardware, or plugins—how do you use them to create something that reflects your unique voice?”

This is the same question one asks when writing for instruments, the same ones that we have had for centuries. The 20th Century saw an explosion of efforts to create new sounds, with a greater focus on timbre as a musical device. We can leave it to the musicologists to explore the details of why this shift occurred, but speaking to my own approach to composition over the last 20 years, it can be explained in a kind of hierarchical sense.

Music can be categorized by dimensions: pitch, timing (or rhythm), amplitude, timbre, and space. Historically, music theory and analysis focused on the dimensions of pitch and timing, with it being less common to focus on timing alone. In the 20th Century, when developments like the percussion ensemble (e.g., Varese) and the introduction of noise as a musical element emerged (e.g. Russolo, Avraamov, et al.). It is the reordering of this hierarchy, with timbre placed at the top, that introduces abstraction. If the public’s focus is primarily on pitch and timing, it’s no surprise that a shift in emphasis leads to debates over whether such music is even considered music at all.

Mort put it simply: “Music is what culture decides is music.”Too much of my time as a musician working in the abstract has involved discussions about my music or music I enjoy, and whether it qualifies as music at all. It does!

It is music because a significant part of our culture deems it so, and refusing to acknowledge another culture’s appreciation of something is on the person holding that view. I no longer entertain these conversations with people who come from a judgmental place. There are too many important things to focus on to worry about such concerns! And I have little interest in conservatism in general. There is a culture around experimental and abstract music that has existed for well over a century, and it is an extension of the classical music canon, even for those who are making statements against it.

After pitch and rhythm, elements like form and orchestration are typically discussed in music. Orchestration marks the first real entry into timbre as a musical device, and it wasn’t formally codified until 1844 with Hector Berlioz’s A Treatise upon Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration, 100 years after the founding of the Mannheim School. While the orchestra has existed as a musical ensemble since around 1600, the modern version developed within the Mannheim School is arguably one of the most exciting musical tools ever employed. The capabilities of an orchestra are vast, with variable instrument groups covering nearly the entire audible range of human hearing, extended techniques, and the potential for spatialization or reimagining (e.g., Henry Brant), and functions as a complete instrument.

Mort discussed the orchestra in depth, viewing the Buchla synthesizer as a template for building its instruments and then composing and arranging parts much like one would with an orchestra. He cites Earle Brown’s Available Forms as a relevant piece to supplement the discussion of his own approach, though Mort had been working in this way for years before ever discovering the piece. In Available Forms, players are given parts that are initiated by the conductor, who provides further instructions on how to guide and cue their performance. While the details are too involved for this text, it is encouraged that any interested listener explore this piece further, as it was all in relation to find what Mort called, “a new new music”.

One last guideline from his lessons is to maintain a policy of performing everything yourself. If you trigger or sample anything from the instrument, the sample should be something that you perform and record yourself with the same seriousness as you would when recording a classical piece in a studio: doing multiple takes, editing them, and ensuring the highest quality result. It is not enough to just sample, loop, and sequence without great care to the process of personalizing it.

I am incredibly grateful for the time spent with him discussing music and its history, technology, composition, the orchestra, and his many fascinating stores about American music and art and those who create it. Lessons that I will certainly carry for a lifetime.

You like to break down barriers and find a dialogue between various (electroacoustic and instrumental) music cultures and heritages. Do you encounter problems related to preconceived ideas, limitations or rules imposed by these respective genres? How can you achieve such mixity?

I wouldn’t say I find problems, or at least not ones that feel personal to me; but I deeply respect the canon, those who came before us, and those creating alongside us. I love and appreciate music of all kinds, but over the years, I’ve realized I’m most drawn to honest music. I enjoy analyzing music through the lens of styles, approaches, techniques, and when it comes to electronic music then also the equipment and technology involved. But in the end, what matters most is that the aesthetic and the statement feel honest.

There’s no formula for finding this honesty, but I recognize it when I hear it. It’s perhaps the magic of music that we all talk about and seek to understand. Mort might call it “qualia”—the indescribable essence that makes a piece of music resonate in a way nothing else can.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

I’ve been focusing more on writing and programming lately. I just finished a book of selected writings from 2009-2024. It covers music, aesthetics, and the ideas I’ve gathered over the years, along with some text compositions.

I’ve been deeply immersed in research at Professor Johanna Devaney’s LUMaA (Laboratory for Understanding Music and Audio) lab at the City University of New York. My work there focuses on audio and speech analysis for musical as well as medical purposes. Right now, we are working with a group out of the University of Toronto analyzing the changes of speech behaviors for those with communication disorders, who are doing regular group singing. Seeing if those exercises help improve or change their speaking abilities. We’ve presented our work at several conferences and festivals the past couple of years and have a couple of publications slated.

I just finished my master’s in computer science at Brooklyn College and am heading upstate to take a full-time faculty position in the music department at SUNY Oneonta. So I’ll be there teaching courses on music technology, production, and history.

What do you usually start with when composing?

I often spend a long time thinking about ideas and forms before ever sitting down to realize any of it. This is especially true with instrumental music —I’ll mentally craft a large portion of the ideas, quickly sketch them out on paper, then move into editing, workshopping, and rehearsing, if that’s an option, before engraving and finalizing the piece.

With electronic music, the workshop and rehearsal phases are always part of the process, so I dedicate significant time there. However, I try to stick to the initial constraints I set during the sketching phase. This approach has become increasingly fluid as my understanding of the lower levels of software and hardware has grown. The ability to refine musical ideas on a microlevel through deep technological manipulation has been incredibly exciting, even though it’s greatly expanded the time it takes me to complete a piece. Which I’m perfectly okay with.

How do you see the relationship between sound and composition?

Since I first started writing music, timbre and form have always been at the heart of my work. As a classically trained percussionist and composer, I have a solid grounding in functional harmony, counterpoint, set theory, and other foundational concepts. While I’ve never been particularly interested in working with those elements explicitly, they’ve profoundly influenced the way I approach composition and sound.

I approach pitch as a timbral device rather than a functional one. For example, playing a low A versus an A three octaves higher on a violin produces drastically different timbres, particularly in relation to the surrounding sounds. In my music, in the vast majority of cases where I’ve written an A, you could replace it with an A# next to it, and the effect would likely remain unchanged. The pitch holds no traditional harmonic or melodic function; instead, its role is purely timbral—a choice made either by me or, in many instances, by the performer.

With all that said, I find that I’m most inspired by composers who work with the elements I don’t typically use, because form is the unifying element of all music. Music is a time-based art, and whether you compose, improvise, use instruments, electronics, noise, or anything else, it all revolves around time. Form is what brings everything together. Philip Glass is one of my favorite composers, and though his sound is nearly the opposite of mine, his treatment of form and direction never fails to captivate me.

Sounds are the events within a form and the form is composition.

How strictly do you separate improvising and composing?

Improvisation and composition certainly inform each other. Improvisation happens in real-time, and so does a composition’s sonic result, but with composition, you can adjust musical ideas after the fact, whether on paper or on tape. Improvisation is making music in time, while composition is making music in space. My written and recorded compositions often incorporate elements of improvisation, whether it’s me improvising or the performers for whom the music is written.

During my studies with Roscoe Mitchell, he made no clear distinction between improvisation and composition, and hearing him discuss it, it made perfect sense not to separate the two. I wouldn’t consider myself a practiced improviser like some artists I know, so I don’t take it that far, but I can certainly appreciate and recognize those who can and do. The difference between a seasoned improviser and someone less experienced is that the former can make adjustments to musical ideas after the fact through their decisions in development.

I can illustrate this with a quick story: About a decade ago, I was in Reykjavik, Iceland, working with Roscoe on his orchestral pieces from his Conversations series. He gave a solo concert as part of the festival, and during his performance, he did an incredible improvisation on solo soprano saxophone. Afterward, several audience members were asking afterward, ‘How long has he been working on that composition?’

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

I have worked extensively with both approaches, and over the last 7 or 8 years, I’ve done more overdubbing and tape music. The amount of activity in my performance career has directly correlated with the amount of recorded music I’ve released. I used to write and record almost entirely in real-time, but now I rarely do. This shift is partly due to the growing complexity of my musical ideas, which require more attention than a single take or track can capture.

This change also corresponds with a noticeable decrease in my scored instrumental compositions. I find that composing in a studio setting gives me a similar sense of satisfaction as writing scores. The ability to go back and revise sections and parts has become increasingly important. When I was writing the bulk of my scored work, I was also actively performing concerts multiple times a week.

What type of instrument do you prefer to play?

I’m a trained percussionist and drummer, and that has always stayed with me. While I don’t perform as often as I once did, I still keep my hands up by practicing rudiments whenever I can.

In electronic music, I typically build Max patches for live performance due to their portability, something that’s key for gigging in the city, and reliability. While analog electronics are incredibly engaging for all the reasons we know and love, they can be difficult to dial in when it matters most. However, as I begin to collaborate more with other performers, I think bringing out these instruments and handmade instruments will become more commonplace.

Obviously, you are interested in gesture, physical move to create the music, right? What is your favorite way to achieve such expression?

Yes! Gesture is paramount in inserting your voice and feel into the music. For me, the best way to do this is to perform everything and minimize automation and sequencing, unless there’s a way to disrupt the automaticity. I’ve always been drawn to the Buchla 112/113/114 touchplates or anything similar, like the Make Noise Pressure Points or the Verbos controllers. Having control over intensity based on finger placement adds so much depth to the performance. Ribbon controllers are fantastic for this as well.

When working digitally, I’ve adapted analog controllers to work with 10- or 14-bit MIDI via homemade hardware to achieve maximum specificity and control. With the development of MPE controllers and software support, this is becoming less necessary, and I hope the trend continues.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

How does it marry with your other « compositional tricks »?

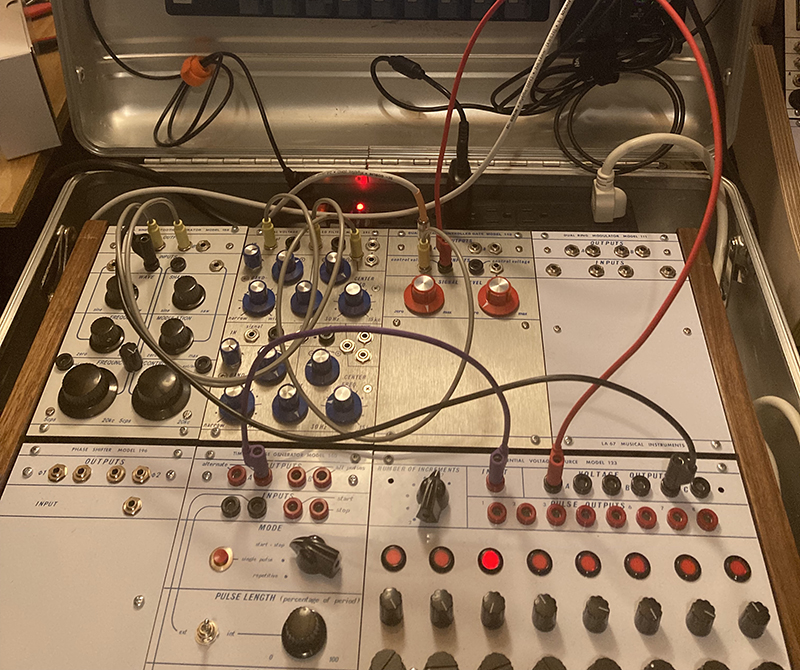

My first exposure to modular synthesis was at Mills College, where I had the chance to work with the Moog Model 15 and briefly with the original Buchla 100. This was in 2009, and while some people were using Eurorack (it hadn’t yet exploded in popularity like it would by the middle of the decade) I had already developed an understanding of the Moog through similar software emulations, but the Buchla was a mystery to me, and I never really got anywhere with it.

There was also a large Dotcom system in another studio that I would use to create huge drones, but I wasn’t immediately drawn to the instrument. That wouldn’t come until around 2016, a time when I was immersed in using minimal technology, primarily radio and feedback circuits, while still writing instrumental music. Eurorack started becoming increasingly interesting as more of my collaborators were building systems. Then I started my own.

Your compositional process is also based upon the use of acoustic instruments that you process or combine with Electronic. How do you work to marry that Electronic with your acoustic matiere?

The performative aspects of both instrumental and electronic music are completely intertwined for me, arguably inseparable, and this is where the marriage happens. A great example of this is in my work Pneuma, a multimovement, mobile-form piece for several soloists and fixed media. At no point in the piece is there live processing of instruments; instead, the performers play to a timeline of gestures alongside audio that represents an already processed version of their instrument. This showcases a relationship between two entities side by side, rather than following a chain like instrument → processing → end result. As I mentioned before, form is the unifying component of all music, and this approach allows for the creation of form in fixed media and along a timeline, where neither relies on the other. Instead, they function more like a duo. This method is consistent in all my music, whether for acoustic instruments, electronics, electroacoustic works, samples, or synthesis. I also like to keep the forms as modular as possible.

When did you buy your first system?

What was your first module or system?

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

My first purchase was a Moog Werkstatt with the CV expander in 2016, and soon after, I added a Moog Mother 32 and Make Noise 0-Coast. These three pieces, patched together, served as my setup for quite some time before I started building a small skiff of Eurorack modules. As far as patching and the mechanics of signal flow, I was reasonably well accustomed to this, having worked extensively in software patching environments. My understanding of data flow had grown significantly since I first encountered the Moog and Buchla in graduate school. About a year into working with semi-modular setups, I was able to purchase a complete Verbos system.

It was at this point that my understanding of everything really codified.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

I think I am still figuring this out! I’ve always felt at odds with technology and music, and it’s part of the charm of the struggle in the arts. I also feel at odds with pencil and paper composition. This is part of the nature of discovery and understanding the world around us and expressing something abstract, like feelings, into something material like music. Electronic music has given me a more real-time strategy in developing these abstractions, and modular synthesizers provide a different interface for doing that. I love working with computers, writing my own software, and diving into the lowest levels of sound that I can, but it can be exhausting.

I don’t think the modular synthesizer has changed my compositional process, but it has given me increased stamina in creativity when I just can’t deal with debugging and designing on a screen anymore.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? You owning an impressive amount of gear, how do you explain that?

I can’t really explain this, but I have experienced it.

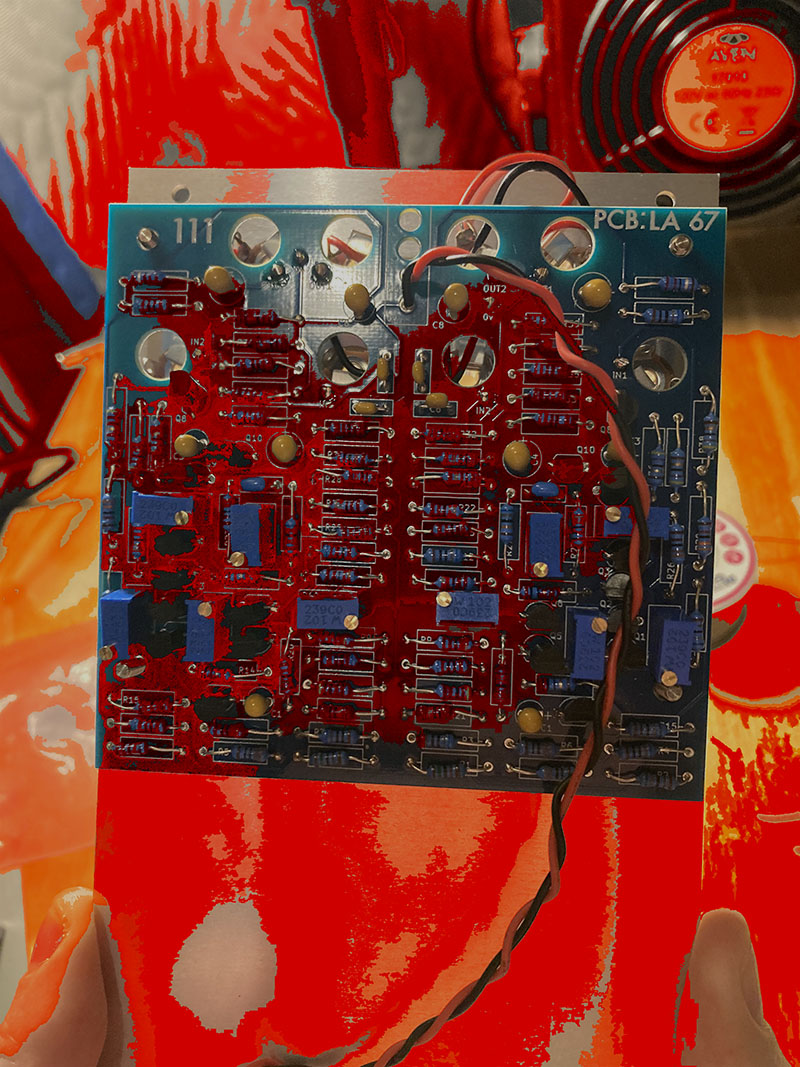

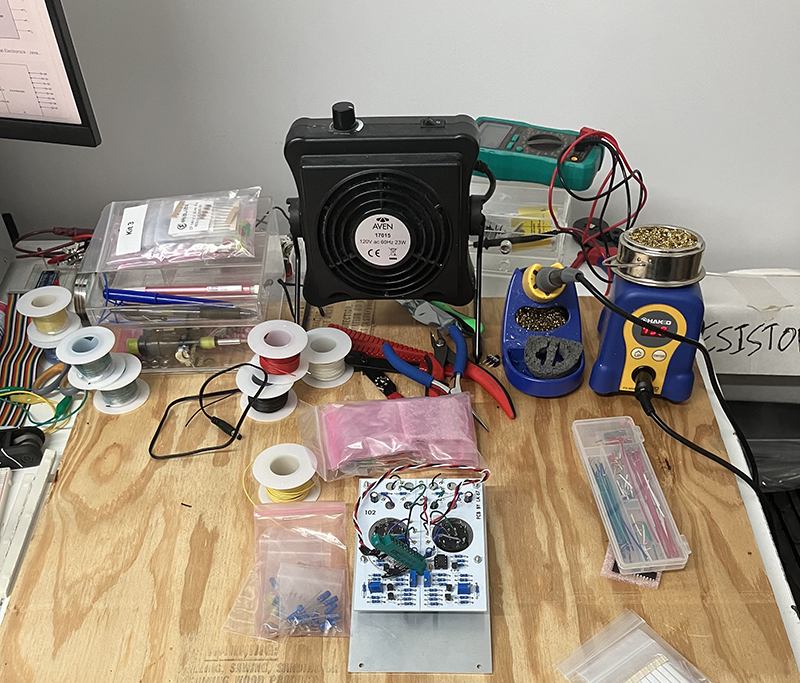

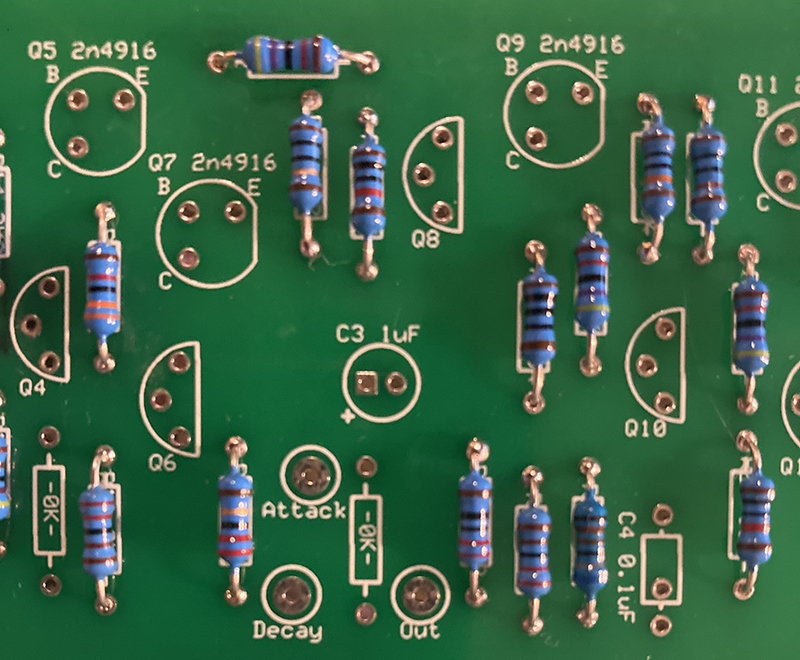

Much of the gear I have has been acquired over many years—either things I have built myself or purchased by selling things I build.

I have a 30-panel 100/200 Buchla system that was constructed with the ‘build 2, sell 1’ approach, where I would build two of every module I needed and sell one to cover the cost of the system over time. Even now, with the system complete, I build, sell, or repair equipment to fund any other purchases, so, for the most part, it’s a self-sustaining model.

There is a bothersome nature of capitalism and fetishization present in modular synthesizers. This exists across music communities, with guitarists, drummers, etc., but the rise of the ‘synthfluencer’ and product development centered around the biannual cycles of NAMM and Superbooth is a bit drab, to be honest. It’s extremely difficult to compose music; it isn’t difficult to listen to or watch someone else compose. What we have instead is a set of ‘tutorials’ online driven by product marketing, or the idea that the next module will write your music for you.

This has never been the case and never will be!

The best remedy to this, for me, over the years, has been to write pieces using just a tape or digital recorder, or paper and pencil.

They don’t ever get released or finished, but they remind me that gear doesn’t make the music—the person does.

Do you prefer single-maker systems, knowing your love for BugBrand or Metasonix, or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs?

I very much prefer single-maker systems. Having the same standards across modules maximizes functionality and range while minimizing hassle and the need to think about voltage conversions or other complications. Eurorack is challenging because standards don’t always span across different makers. The Eurorack system I currently have consists of all the ARP 2500 Behringer reissues, along with a couple of matrix mixers, and that’s it.

Well-designed modules can be used for multiple purposes, so I tend not to get caught up in the releases of the latest modules.

How has your system been evolving?

The last couple of years have seen my Buchla and Eurorack systems remain the same, and I anticipate that will continue moving forward. After much trial, error, and exploration, I’ve found a combination that works with everything I need, promotes gestural control, supports different styles of synthesis, and offers a level of sonic construction with immense potential.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

I don’t see module choice and organization as part of my compositional process, but I think some artists do, which is great. Having worked with so many different types of equipment over the past 20 years, I feel confident I can write the music I want on any available gear. Of course, the result will be different from piece to piece, informed by the technology, but that’s what I enjoy most about composing electronic music. The piece I write using an MPC 1000 will be different than one created on a Buchla, but it will still be my music—the music I set out to compose.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

Both.

It depends on where things go. I don’t always have a plan for a composition; sometimes I just like to play and improvise, finding new ideas and techniques along the way. If something resonates and calls for an external device to come in, I’ll roll with it.

I don’t have any rules about it.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

Yes, I pre-patch, and for certain pieces, I’ll have planned changes for repatching on the spot. I have my own policy of using the most portable system possible when playing live, so this is necessary. There’s always an improvisational element at play, especially if the system isn’t behaving as initially expected, and I have to adjust to get the desired results.

Which module could you not do without, or which module do you use the most in every patch?

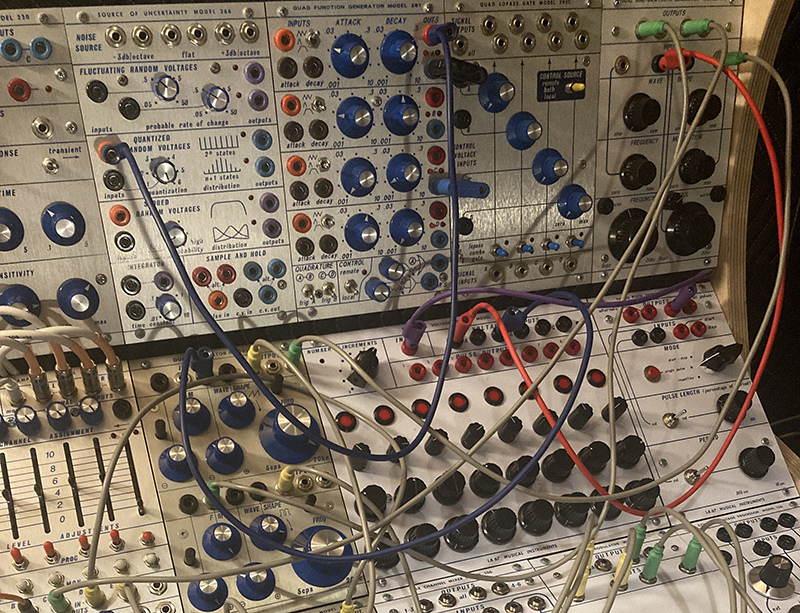

Any random source. Randomness is a consistent element in my music and always has been, either to introduce variation that doesn’t require constant attention to detail or to push the idea of randomness itself. I love any random source in any system, and my all-time favorite is the Buchla 266 Source of Uncertainty. It’s simply perfect in its range and versatility.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

With the development of computers and software over the last 20 years, I don’t think there is much now that cannot be achieved outside of that. Ableton Live and Max/MSP alone offer more possibilities than I could ever care to conceive, but this was not always the case.

For years, modular synthesizers provided an accessible means of automaticity in music, which still exists. I think this is what sets them apart from traditional instruments, which was not able to be replicated—at least easily—until software allowed it without needing specified knowledge in programming.Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

I have used several software modular pieces but never latched on to any except Max/MSP, if you count that. In the mid-2000s, VST instruments and standalone software were the primary entry point into electronic music for me, so I spent a lot of time with those and Reason.

I never really returned to them in a meaningful way other than to explore, and I would say it was mostly because I had working knowledge of Max that got me where I needed to go with synthesis.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

Honestly, the one thing that has piqued my interest that I would never actually purchase is the Analogue Solutions Colossus. I love the idea of a massive studio centerpiece with so much power and variety, but the cost is just crazy excessive. I appreciate the level of care and craft that goes into building instruments like that, and I think it truly justifies the price tag, but it is just another league.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Which ones?

As I mentioned earlier, Luke DuBois is probably the most engaging player out there that I have seen lately. The blends of sonic and visual elements are striking and always well executed. Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, who is also here in New York, with his use of voice and clear command over the instrument, coupled with a great range of musical history that he has been a part of.

Bob Ostertag for his music but also his commentary on the subject, especially in his book “Facebooking the Anthropocene in Raja Ampat”, he has a great essay on electronic music performance.

Finally, I have to shout out Las Sucias, a Bay Area duo with Danishta Rivero and Alexandra Buschman, both fantastic musicians in their own right. Their live show is raw and powerful and incorporates highly creative uses of the instruments and ritual. I was fortunate enough to share a bill with them not long before moving to New York, and they have an album out on Ratskin Records that has been one of my favorites for years.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

Pauline Oliveros was my first big influence that expanded what I thought possible in live electronic music performance. Her early works with tape delay feedback are incredibly groundbreaking and, in many ways, criminally overlooked. With essentially a few pieces of equipment, she creates an entire sound world, all in real-time, which was unprecedented at the time. She used that system for years, and her works with the Buchla and Moog are still among my favorites.

Mort’s earlier Buchla pieces like Silver Apples, Sidewinder, and Touch are all a constant source of inspiration. I feel incredibly fortunate to have studied with both him and Pauline, discussing their compositional approaches and use of technology. It’s really something to explore their music as a listener, gain an understanding, and then be able to sit and learn their techniques firsthand, feeling that understanding change. It’s quite special.

Éliane Radigue’s music is a favorite and demonstrates a level of focus, discipline, and control of the instrument that only a few can achieve. Her works prior to using the ARP 2500 have this too. Working in feedback is challenging for several reasons, and like Pauline, she maintains absolute control that really showcases a thought and practice you can clearly hear.

Composers who used modular systems for tape music have been hugely influential to me in the last decade or so. Bernard Parmegiani is arguably my top favorite in that category. His attention to sonic detail, form, and organization while maintaining an incredibly engaging ‘liveness’ in the music is unrivaled.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Just do it! Experimentation is key. Take risks and always appreciate that limitation breeds innovation. Build or learn to build the modules if you can, it saves money and gives the instrument more ‘soul.’ Don’t get hung up on equipment or the next best thing; work with what you have. It’s always enough!

https://www.danielmckemie.com/