Julien Palomo lives in Paris and likes to be discreet even if he has been active in our Experimental scenes for quite some time now… Founder of the label Improvising Beings devoted to improvisation, provoking encounters and, at the same time, paying homage to an underestimated part of the radical musics of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, especially Free Jazz but not only…

« Electronic experimental music is a childhood dream come true. I am a former free jazz producer and have tried to bring this freedom (within certain laws) to the life synthetic, under the influence of Alan Silva, Conrad Schnitzler, MEV… without being necessarily true to their word. Traces of noise and chaos, Radigue and Penderecki, or André Stordeur… Raw materials, texture, timbre: the Universe, Nature, the All, God, whatever you call it, is first and foremost a continuum, and by insisting on long-form compositions, I want to reflect that. Sometimes I will cull a chunk that makes sense to me.»

Julien himself fluently speaking the language of EMS and ARP and frequent collaborators include Michel Kristof (in Other Matter), Fabien Robbe, Skoddie (in Androchist). Projects and good memories with Henri Roger, Vincent Eoppolo, Vinnie Paternostro and Jay Reeve (United Slaves), Philippe Neau, Sato-San.

He’s been with us since the early days of Modulisme, gracing us with one of our early Sessions :

https://modular-station.com/modulisme/session/30/

Now disabled and in forced retirement, Julien would like to thank all and everyone who has supported and understood his music and productions over the years. Thanks for the memories. He hopes to curate more of his vast archive in future.

He especially acknowledges Michel Kristof, Eric Zinman, Fabien Robbe, Alan Silva, Ivo Petrov, Paulo Motta and Modulisme for their unwavering support and dissemination of his music.

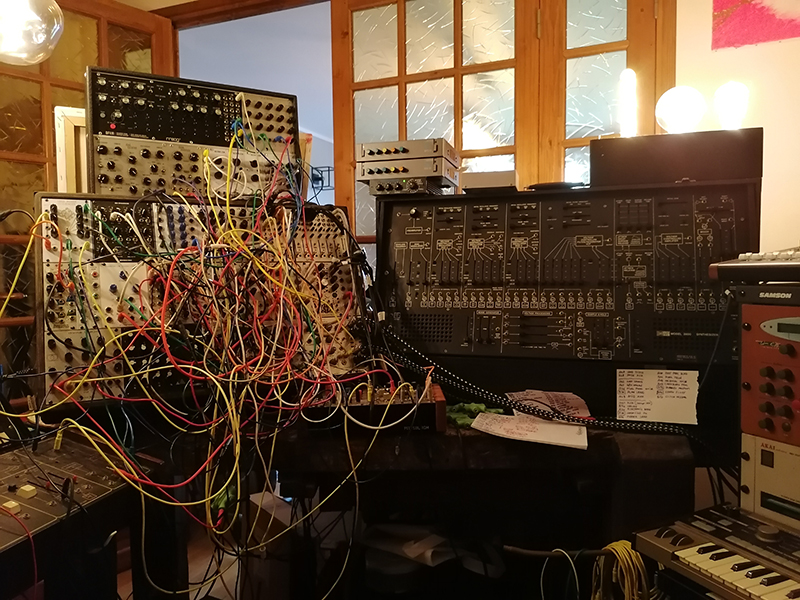

PS: Live photos courtesy of Patrick Lainé.

It’s been a while since your first Modulisme Session so what have you been working on in the meantime?

Thanks for inviting me back. As it turns out, my first session for Modulisme was also my last significant statement for three years. In the meantime, I’ve lost a few battles against multiple sclerosis, and disability has prevented me from sitting in my studio as much as I wanted/needed. I have returned to my synthesizers in March of 2023, and the results are what you are offering.

Still, in 2021 a few projects I had initiated before this period of forced retirement came to fruition. A very experimental cassette with dear friend Autumn [Altair], an archive download of my long-standing band Other Matter with Michel Kristof, a CD with Makoto Sato and Michel Kristof again in a free jazz setting. In the summer of 2020 I also put a triple album in the can with Alan Silva, the legendary bass player, who’s inspired me to play synthesizers in a free improv context in my 20s. The two of us put together an orchestra of six 1990s-2000s digital synths. Disease has prevented me from taking care of finding a proper venue for its release. This fall, I recorded another synthesizer duet with Eric Zinman, Other Matter has reconvened, and I’m putting the last touches to a contemporary music album with Fabien Robbe. I am immensely grateful to those friends who fought hard to keep our music alive while I was out.

My only regret is that 2024 again finds me without label, and quite unable to chase one. All the more that the world of free improv, it seems to me, remains quite diffident towards synthesizer music. Minimal acoustic music is the order of the day.

It’s been a few years now since you stopped your label, would you like to look back on this period of your life? Do you miss this activity?

I do and I do not miss it. First and foremost because I can’t do it anymore. Running a DIY label means spending lots of time at the post office, or cramped behind a computer, or socializing at concerts – all things I can’t handle anymore in my condition. Though I wasn’t thoroughly diagnosed in 2017, I was physically on a bad slump and that’s one of the reasons I quit, – that and declining CD sales.

No regrets. Working with those artists was fantastic, whatever the hardships, and there were many. I can’t begin to describe how it changed my life. Gave me the strength of returning to music myself, of leaving the nine to five job…

No regrets also because I didn’t have the abilities to adapt to the fast-changing landscape. More streaming, more cassettes, more LPs, more social networks, while my skills are antiquated – 2000s CDs and mailing lists! And I’ll be honest, that’s not what I signed for twenty years ago. I see artists and producers struggling harder than I did with all these factors and admire them all the more.

I had it easy dealing with distributors who basically sold records for you – do you remember the days of selling records?…

Time hasn’t come yet for recognition and legacy. Improvising Beings irked many. It ran counter to my «peer’s» expectation of what improvisation is supposed to be in the 21st century. Recently, I have entrusted some of the albums to Atypeek music for digital distribution, to stave off piracy and keep the music alive.

The kind of free jazz I defended is disappearing with the people who initiated it in the 1960s. François Tusques, Alan Silva and Sabu Toyozumi remain, and of course friends who are in their 50s and 60s, but mentors Itaru Oki, Burton Greene, Sonny Simmons have passed away. It’s statistics, but it’s hard on me. Without them, it’s another story altogether, and there’s no place for Improvising Beings in that new story.

What do you think of the way the experimental scene has evolved since then?

I’ll be honest: I don’t really identify with improvisation as I hear it today. It seems jazz has finally left the equation, and I was into free JAZZ. I hear lots of virtuosi with academic training, and there’s so much cleanliness I can take. Improvising Beings was untidy. It started in a health hazard of a building in the suburbs of Paris, printing CDrs in my kitchen. Leaking toilet, cockroaches, police raids… I’m not into white post-rock parading as improvisation either. We get a lot of that too.

Allright, I’m unfair. Truth is, I haven’t been able to listen to enough music and research contemporary scenes properly. Hospitals are good for conducting field recordings experiments (I have to record an MRI before I die), but that’s all there is to them, musically. Add to this that thanks to MS I am slowly losing my left ear. As much as I love electroacoustic music, I have trouble with surround sound, moving objects – I can’t locate sounds in space anymore and spatialization makes me dizzy. I’ll make do with light stereo. But I doubt electroacoustic music will make room for a mono composer… Same with visual arts and video, as more and more experimental music goes with it; I can’t cope with a moving visual field. My technological environment is returning to the 1960s.

It’s enough that I keep myself informed with the output of artists I know personnally. Roughly a hundred people! It’s not lack of intellectual curiosity, it’s disability 101, sadly.

The state of the record market? The return of the overpriced vinyl format, reserved for the middle classes?

Like I said earlier – nope. I resigned. As far as my own music is concerned, I need the cosy safety of CDs or digital files to ensure my intentions (frequencies) are fixed properly. I can deal with cassettes because I like the grain and if I can work closely with the engineer in charge of committing the files to tape. Hiss is my daily life – I have a complex but fruitful relationship with my tinitus. «She» is probably my muse.

With the increasing quality of digital files available for stream or download, I don’t see the point in selling music over 30 euros, 45 with shipping. Especially music which doesn’t find a public easily, to start with. It’s another bar. It’s close to gatekeeping. If you don’t have the cash, if you’re not upper middle class, you can’t listen to it, and you can’t be one of us as an artist… Is that it? OK, if those steep prices meant the artist made more money, I would cautiously consider it a viable economic model. But 85% of the budget of those productions goes to the LP factory. If you have that kind of money, put it in the artists’ pocket dammit! I can’t condone an economic system where, as usual, the art/artist is the cheapest commodity in the chain.

Of course streaming and downloads don’t pay either, or close to nothing. Economically, they are not the solution (they could be if they were not another catch made up by the tech giants, who are worst at handling music that the «industry» of old). But at least no one has to skip a meal to discover my music.

Would you like to go back to that period when you first discovered modular synthesis, the first stirrings, how it all took shape for you? How did it unfold and what lessons have you learnt from it?

Allright, quickly, because I have dwelled on gear questions at length when we discussed my first session. The learning curve wasn’t too steep, because it was a childhood dream come true – gazing at the credits section on the records and wondering what on earth an ARP 2600 is. I dabbled in piano, in organs, then in synths doing imitation sounds, then in synths you can tweak (the microKorg), then in intimidating crazy synths (the Waldorf Microwave), and finally, being for the first time bed-ridden in the throes of multiple sclerosis, I had plenty time on my hands to read manuals and step into modular. It was a quick escalation, boosted by a severance package from my job. Thank you, former job.

I was already familiar with electronic experimental music as a listener since my early teens. I recognized the sounds the minute I switched a modular synthesizer on. It felt oddly familiar. Friends could tell you – suddenly, it felt like I had found the right extension for my derelict body. I practiced ten hours a day for a year. I challenged myself hard. It helped me keep my sanity together during this long illness.

When did you buy your first system? What was your first module or system?

That must be late 2015, EMS Synthi E and ARP 2600 plus sequencer, in quick succession. By the end of 2016 I supplemented them with Eurorack and found the resulting system to my taste in 2019. It hasn’t changed since.

Concurrently, I was learning to programme digital synthesizers to get an altogether different array of textures and timbres. My instruments of choice became the Waldorf Microwave, whose architecture is very modular, and the Korg Z1, whose pre-software era brand of physical modelling is important to me in regard of my background in acoustic free jazz.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

Ten minutes. I was dealing with the Synthi E where anything goes anywhere, and it will produce any other painful squeal effortlessly. After all it was an educational modular, very clear layout and instant results.

Likewise, credits to ARP synthesizer for designing the 2600 – it is crystal clear. I for one am very happy it became a popular instrument through reissues, it’s an interesting starting point with more twists than people think. The 1971 manual is a straightforward course in basic modular architecture, and I advise beginners to read it.

My learning to patch these two modulars helped me master the programming of digital syntesizers very quickly.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

Look, I’m not a great essayist. I’ll try anyway. Let’s start with the obvious. Electronic music, oscillators are witness to the most fundamental aspect of the universe, vibration. No vibration: nothing. We know things by their frequency, their amplitude, their phase relationships, their envelopes (time shapes), and their spectra (mix of vibrations). This is no abstraction. This is no maths. This is a very central, very personal, intimate issue.

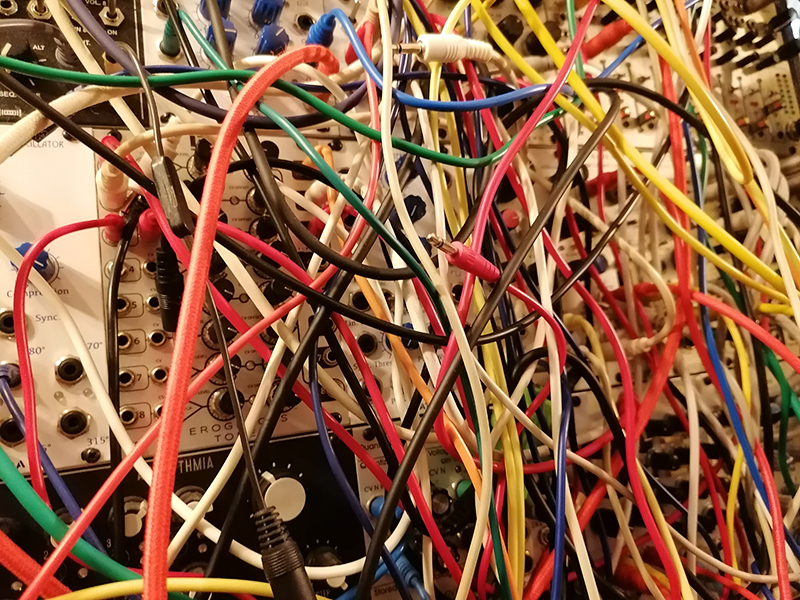

Multiple sclerosis is mostly a degeneration of the nervous system. The nervous transmission of voltages is severely impaired. I see a form of poetic justice in all this. I am my worst patch ever, outs connected to outs – uncanny, unscheduled disruptions… It shaped my ideas of what music is: first and foremost a gentle channeling of electric current, as if I was exploring a metaphor my own nervous system, and a voice for the sensory hallucinations I experience on a daily basis.

The system and my body are dealing with the same fundamental force – electric current, vibrations. I am domesticating my enemy, this unruly chain of electrons who constantly dodges the norms of how a decent nervous system is supposed to act. Whenever I can hit it, the system expresses what my body can’t otherwise accomplish. My days as a keys player are numbered as my left hand fails me: electronic instruments, which I’ve seen in use in physical therapy and geriatric care, don’t require as much gestural virtuosity as other instruments. Contrary to acoustic instruments, there are no conventional gestures to play synthesizer, especially modular. There is no grammar of «put your finger there, pinch this string this way, hold the neck that way». Each performance will present a situation that will call for a gesture you haven’t visited yet, and it’s good for your brain. It is a very unique, destabilizing use of the body, which is suitable for dysfunctioning bodies. In a sense, where virtuosity in an acoustic instrument is in the body, on the contrary synthesizers help you develop intellectual alertness that doesn’t necessarily call for physical agility.

That’s why I devised a slow, droning music where events are more or less foreseen, and don’t require me to act impulsively. All I do is gently nudge controls, open and close channels whenever I see fit, chose to unleash a pre-programmed event on the digital region of the system… The drone has probably been there since an ape-like figure started to mumble a monotone chant between his teeth to reassure himself when night and demons invaded his environment every day. It’s a natural expression of our awareness that forces beyond us are constantly at play behind the veil of our broken, unnatural daily deeds. We know there’s no silence. We perceive that permanent hum. Sadly Renaissance loathed «peasant» artistry which always relied on the drone, the «bourdon» for instance, over which there would be one or several leads. Renaissance burdened us with notes and their relationships. That was the idea behind the developments some of my mentors like François Tusques or Alan Silva brought to free jazz: reconnect experimental music to the people through the presence of droning elements. Tusques got the hint from Sunny Murray’s continual wall of percussion. Straight from post-African popular and/or sacred music… Likewise, Ornette Coleman’s concept of harmolodics freed the relationships between pitches from the diktat of notes… I don’t like to use silences in my compositions. Thanks to tinitus I haven’t heard silence in decades, it means nothing to me. I see all my pieces as excerpts of a continuum. I can stay several months on the same patch and still steer it in noticeably different directions.

The same collection of modules can be used in a dazzling different ways. So I don’t use the modular as an instrument, but as an orchestra. I prefer the vintage designation, «electronic music studio». A patch is a micro-composition, and I combine those micro-compositions in a larger ensemble. And then I conduct those voices pretty much like a director, certainly not like a performer. I even allow those voices to improvise. Synthesizer allows you to do that: either you intervene a lot, either it creates something along the lines you defined, and it gives you fresh ideas in full flight. You can even let it stray away for good and run amok…

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? How do you feel about that?

How has your system been evolving? You know very well your instruments, would you need some more?

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

I built it over the course of three years, a little less. I’ve always had a fair idea of what I needed, what type of oscillators, filters, utilities, effects. I do appreciate what I hear of other modules in videos or records, I know I would have fun trying them, and I also know I have no room for them in my music. Mostly, I needed functions that could add to the Synthi E and the 2600 (more LFOs, more inverters for instance, or doubling the capacities of oscillators and filters with circuits inspired by EMS and ARP), and would facilitate the integration of my analog and digital synthesizers. That, and that only, dictated the evolution of my system. And no, I’m not a MIDI guy – it’s all CV to MIDI! Which creates numerous happy accidents along patterns I have carefully programmed. Norm, and acceptable/unacceptable deviations of the norm, as I explained earlier.

In and out of that, I understand the fun element people find in acquiring new modules, even if I don’t share that attitude. Provided they’re not naive enough to think they’re acquiring new ideas, which module manufacturers are rather quick to sell you? It’s a great hobby as long as it’s not fetichism. Just keep an eye on music-making, people, and try the three module challenge before you decide to «get more». But then, who am I to give any kind of advice. Do’s and dont’s are not my style. Whatever it takes for people to express themselves, I find OK.

Now, if I was to explore a new direction – it’s part of my original plan, and I never had the funds to implement it – I’d explore pitch to CV as several friends would like to experiment co-controling the system with their acoustic instruments while I use their lines to programme events on the fly, and/or to modify their sound to augment it. Again, I’m obsessed with cohesion, with a whole that can be expanded to encompass more sounds, ad infinitum.

Do you prefer single-maker systems (for example, Buchla, Make Noise, Erica Synths, Roland, etc) or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs. ?

I combined both approaches – self-contained mini-systems, the Synthi E and the 2600, that I can opt to play alone, or integrating them in larger collections of modules, and even non-modular elements. Provided it remains an ecosystem. Obviously I’m the Roland Kayn type who sought to create an environment in which he could freely move. Or maybe more of the Conrad Schnitzler kind, buried as he was in his basement surrounded by walls of interconnected devices.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

Outboard I have old, colourful effects (understand shitty): Dynacord VRS-23 and DRS-78, Alesis Microverb (dirt), Boss RPS-10 (more dirt).

I record directly in a Tascam Model 24. I don’t use the computer during the recording process. It comes later if I need a bit of editing (the less, the better), compression, or if a composition requests heavy layering of several recorded performances – «tape splicing».

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session? Is there a story, what was your intention?

All aforementioned instruments and effects were used in this session: ARP 2600, EMS Synthi E, ARP Sequencer, Eurorack (of note: circuits by Plankton, Livewire, Nonlinear Circuits, Livatera, Elby, Mystic Circuits…), microKorg, Microwave, Z1. Eight voices total. With roughly twenty sound generators, thirty filters, a zillion functions at play, digitals offering a library of 300 custom presets, themselves involving sound generators, filters and functions, the patches I used are indescribable.

I tried shorter pieces on your suggestion, to highlight the properties of timbres and textures I really enjoy. All the more that as of yet, I haven’t recovered the physical ability to withstand long working sessions. In a sense, I improvised a bit more than I used to, and tried to work on a basis of not combining too many ideas. They’re bricks of larger ideas I’m storing if I can return to long formats of several hours, which is what I’m known and loathed for.

There’s definitely a story of overcoming challenges to regain the means to expressing oneself. It’s all a bit jubilant in a dark way, and scratchy – improper sounds for improper times. I didn’t come up with titles: they have no life of their own, they are me.

Which composers are you feeling close to these days?

Close? No one. It’s too personal an experience.

But there are lots of people whose work I enjoy, modular composers or not: Richard Scott, Cesario Fa, Foussat, Phil Durrant, Kurt Liedwart, Susan Drone, the late Ronald Pellegrino, Doug Lynner, Rafael Timoner, Rick Reger, Forest Fang, David Morley, Robert Rich… I probably mentioned the same people three years ago!

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

Pauline Oliveros’ Bogs for sure. Lesson: (ominous bubbly and toad-like sounds).

Eliane Radigue obviously, hence my fondness for ARP. Lesson: patience.

Bernard Parmegiani’s use of EMS. Lesson: disrespect the outcome of the session, don’t surrender to the sound of the synthesizer, don’t fetishize it.

André Stordeur who subtly combined analog and digital. Lesson: exhaust the idea.

Conrad Schnitzler. Lesson: fullness, more fullness!

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

As above: no do’s and dont’s!

Recent recordings of Julien Palomo have been released by the great label Mahorka, feel free to check: