Fernand Vandenbogaerde was born in 1946 in Roubaix.

Musical studies in Roubaix at the Conservatory, at the Schola Cantorum in Paris, and at the National Superior Music Conservatory (CNSM) in Paris. Still at the CNSM, he attended Pierre Schaeffer’s classes and INA/GRM’s session, then in Köln and Darmstadt, composition classes with Stockhausen, Ligeti and conducting orchestra classes with Bruno Maderna + also attended IRCAM’s course, as well as Henri Pousseur’s seminars at the American Cultural Center in Paris.

In parallel he has completed several works of analysis of mathematical music such as Xenakis + has lectured and written articles on various topics of experimental music.

In the field of electroacoustic composition, he participated in the founding of the Groupe de Musique Expérimentale de Bourges (G.M.E.B.) in 1970. From 1969 to 1975, he was responsible for Creation and Distribution at the Centre International de Recherche Musicale (C.I.R.M.), first at the Schola Cantorum in Paris and then at the Conservatoire Municipal de Musique de Pantin. In 1972, he set up one of the first electroacoustic composition classes at this institution and established a studio, which he managed until 1982.

In this context, he technically produced electroacoustic works for numerous composers and was responsible for the sound engineering of concerts for various contemporary music ensembles.

As a composer, his works have been performed at main contemporary music festivals in France and abroad : Germany, Switzerland, Brazil, ltaly, Argentina, Mexico, Uruguay, Spain, Holland, Belgium, Portugal, Poland, Yugoslavia, USA, Israel, Austria, Romania, Albania, lndonesia, Hong Kong etc.

From 1976 to 1997, he was director of the National School of Music and Dance in Blanc-Mesnil.

From March 1997 to April 2014, he has been General Inspector of Artistic Creation and Education in the Music, Dance, Theater and Spectacle Department of the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.

ITERATIONS

For 4-track magnetic tape (also available in 2×2-track and 2-track versions for radio broadcasts).

On a framework (same material as for “T.E.M.,” “Time – Space – Matter”) whose spatial evolution is caused by beats and interference between the 4 channels, a series of brief elements are grafted on. The evolution of the articulation of these elements tends to mask the initial framework at times (in both cases, these are almost exclusively iterative sounds).

Magnetic tape recorded at the Utrecht Soundology Studio (Netherlands) in September 1973.

Premiere: April 8, 1974, in Paris (Théâtre Présent), then in other venues in the Paris region.

KALEIDOSCOPE

This piece is presented in the form of five distinct but linked sequences, some of which are in four tracks and others in two tracks with different spatial localization. The tiling is done live, leaving room for interpretation depending on the spatial and acoustic possibilities of the broadcast location (a 2-track mix is made for radio broadcast of the work).

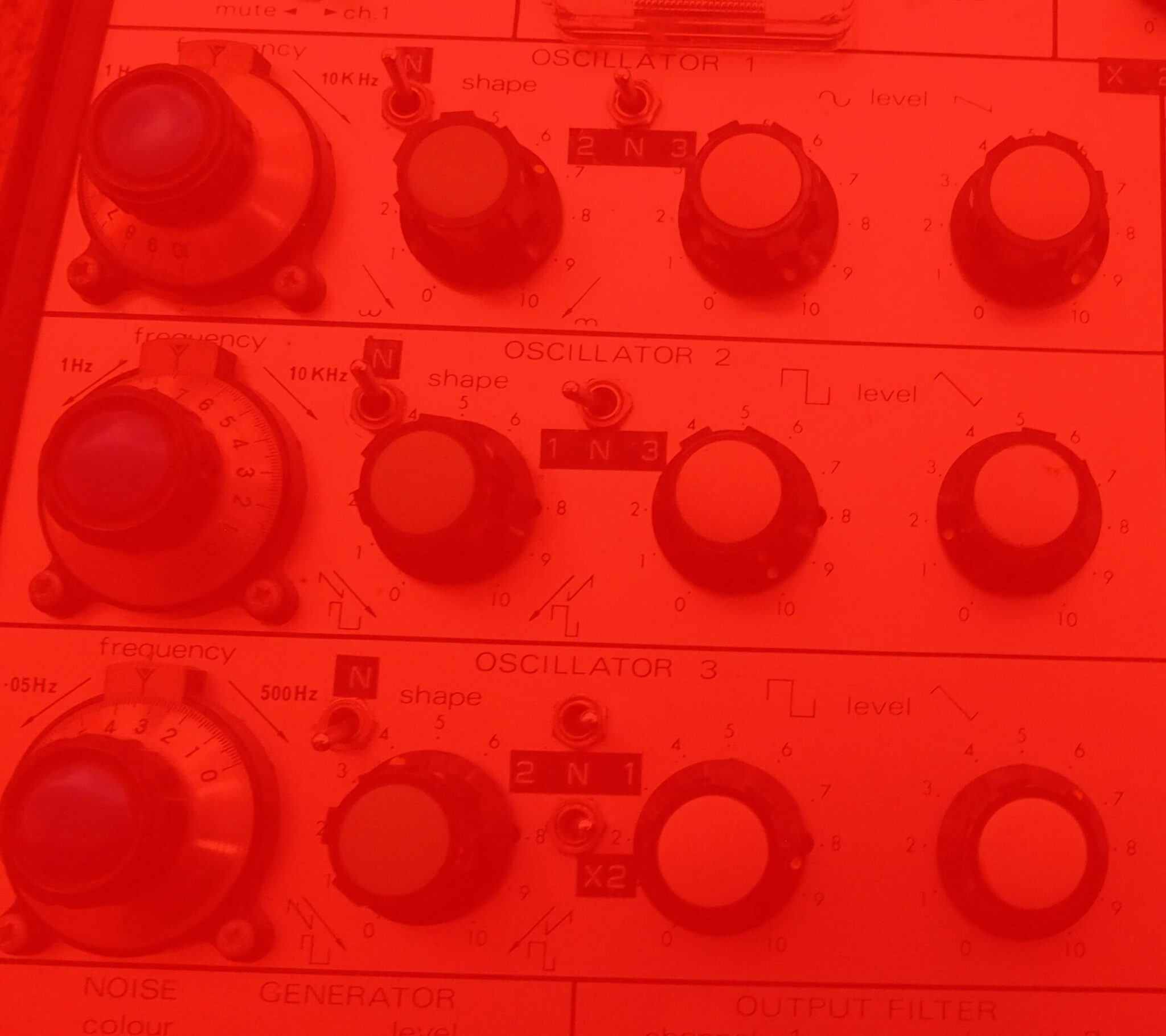

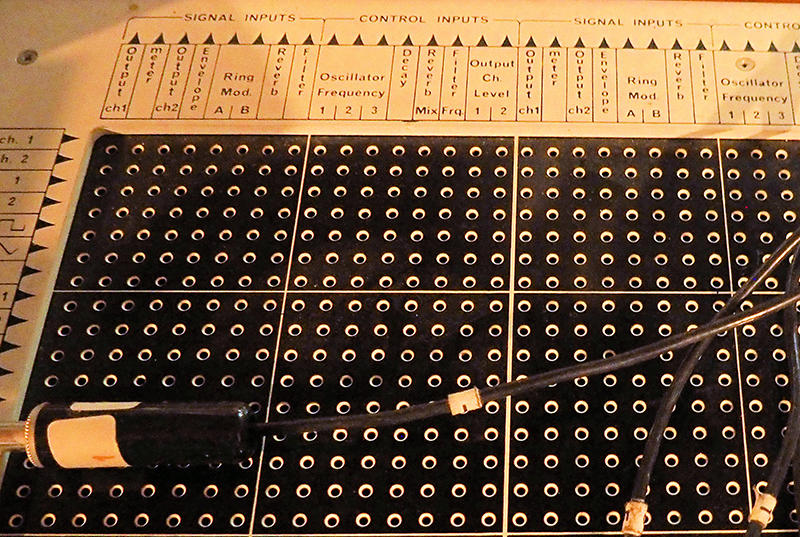

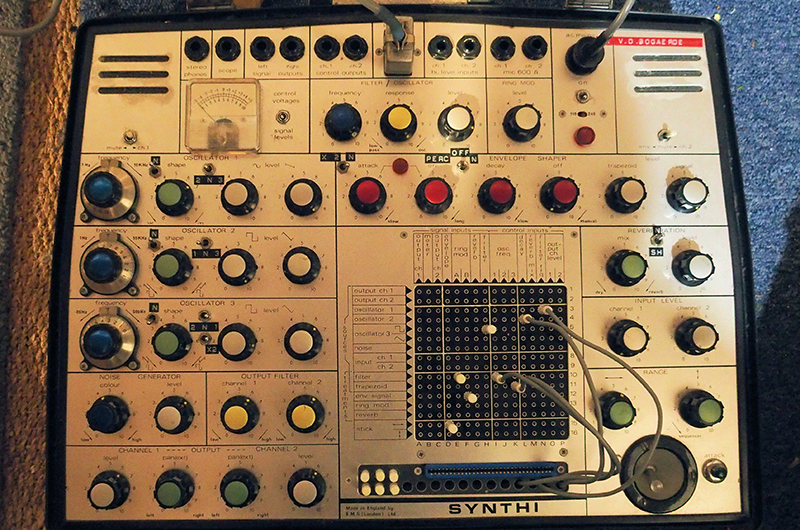

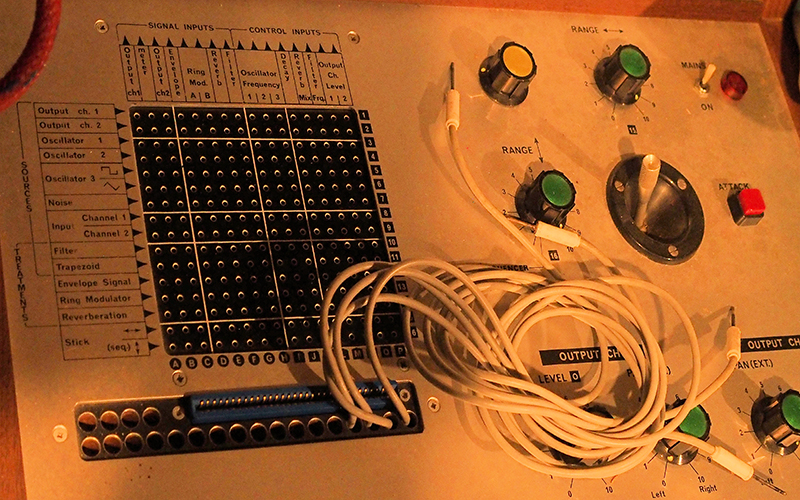

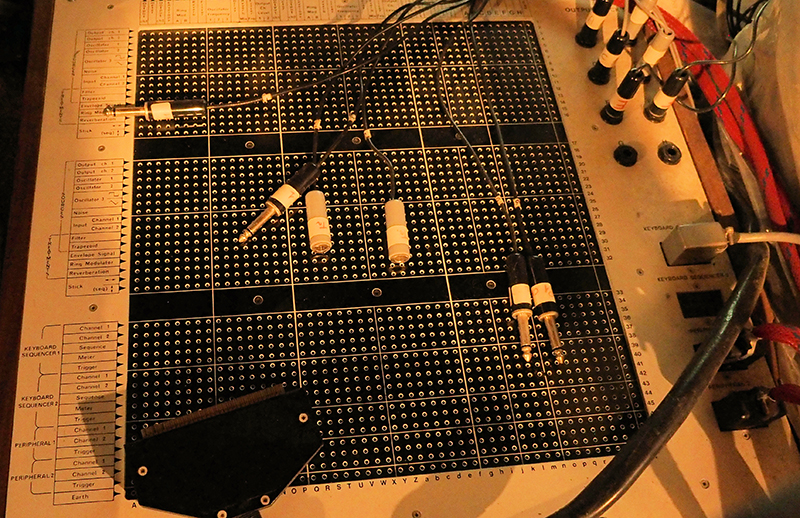

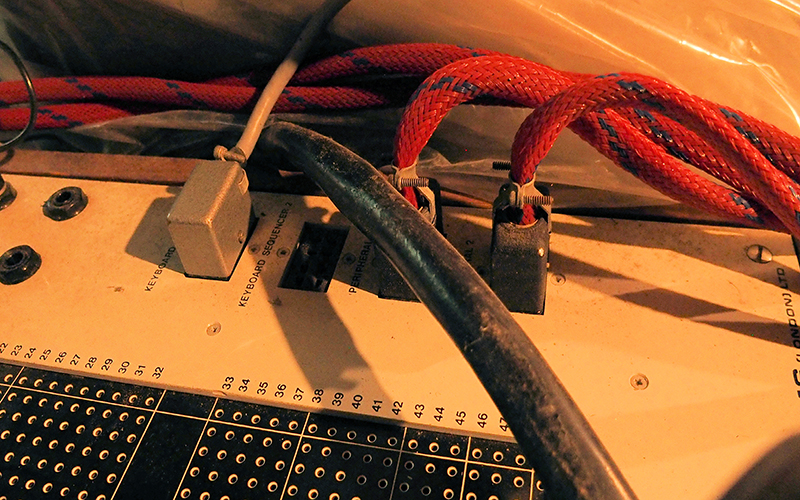

All sounds were produced using two A.K.S. synthesizers and a Synthi 100, partly at the Electroacoustic Music Studio of the Municipal Conservatory of Music in Pantin and partly at the Electronic Music Studio of the University of East Anglia (Great Britain), where the final production took place (in September 1976).

The premiere took place on November 19, 1976, during the Rencontres de Musique Contemporaine de Metz.

This was followed by other concerts at the Abbaye de Sylvanès, Pisaro (Italy), Bourges, Paris, Montevideo.

L’APPEL DES PROFONDEURS (THE CALL OF THE DEPTHS)

This piece was created in early summer 2025 using electronic sequences dating back to the end of the last century!

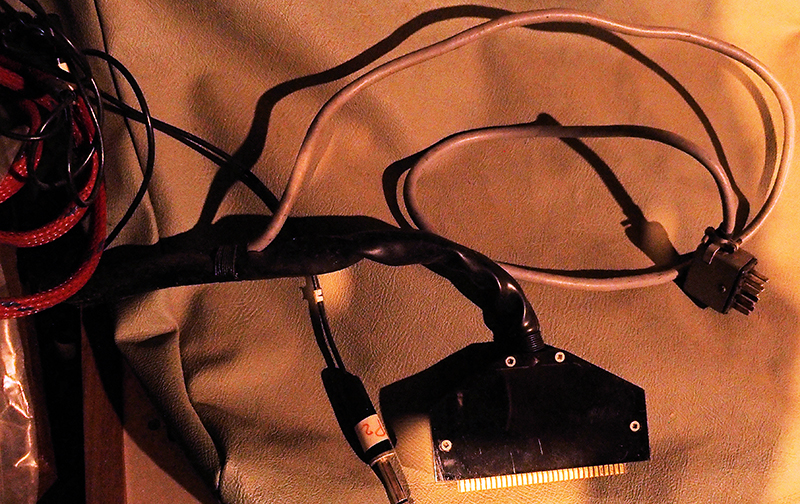

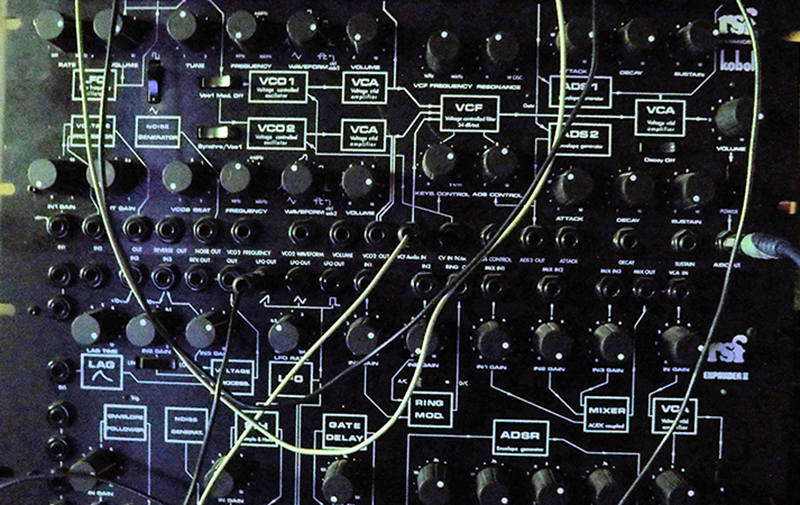

These elements came from an AKS synthesizer + a VCS3 from EMS, as well as two Kobol modules from RSF.

They were just waiting for me to decide to manipulate them, transform them so that they could take shape, and give them a title.

Until now, no one has heard this piece in concert. The listeners of “Modulisme” are therefore the first audience!

The invention of recording by Cros and Edison (1877) made it possible to manufacture machines that could manipulate sound. Studio music was born. Could you define Musique concrète, Music for Tape, and Electronic Music for us?

Indeed, it was the ability to record sounds, voices, or music on a medium using a “machine” and then play back that medium on another machine with sufficient “fidelity” that made it possible to preserve music in a completely different way than engraving it on sheet music, which then required the presence of a performer to be reproduced.

But let’s not kid ourselves: the primary purpose of playing a floppy disk or magnetic tape, and the invention and commercialization of the tape recorder, was not to create “music” but to be able to “preserve” speeches, ceremonies, existing musical works, etc.

The “birth” of this music is a diversion of devices and practices!

It took the genius of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry in Paris (and a few years later Karlheinz Stockhausen and Professor Herbert Eimert in Cologne with electronically produced and recorded sounds) to make us realize that manipulating recorded sounds could give rise to new forms of sound production and reproduction and, therefore, also to a new way of conceiving music.

The various names — musique concrète, music for tape, or electronic music — are not very meaningful because they use either the name of the medium or the mode of production. However, the medium has evolved from reel to floppy disk, magnetic tape, compact disc, and now computer files or the cloud. What will the next medium be? Thus, as far as I’m concerned, I prefer to stick with the term “Electroacoustic music” which seems to me to be the most general one.

A musicologist analyzing four of my pieces for a CD booklet wrote that I used “the means of concrete music with electronic sounds to create these works.” The name given to this music cannot be reduced to the types of sounds or their processing or the media used to preserve them.

In 1955, Peignot proposed the term “acousmatic,” but Schaeffer ultimately rejected it, declaring that “electroacoustic” was the most appropriate name for this practice. In the early 1970s, the GMEB developed a process for broadcasting and filtering multiple loudspeakers, creating a spatialization instrument in its own right… The following year, François Bayle appropriated the concept and chose to adopt the term “acousmatic.”

I admit that I don’t really like the fact that the concept has been elevated to a “school” and that we talk about acousmatic music, a genre, rather than electroacoustics. What do you think

The Gmebophone, invented by Christian Clozier at the Groupe de Musique Electroacoustique de Bourges, and François Bayle’s Acousmonium at the Groupe de Recherche Musicale are, in my opinion, tools for broadcasting music on media. But they are just tools, nothing more.

The first electroacoustic music concerts took place in concert halls where the musicians or orchestra were replaced by two or four speakers on stage and possibly two speakers behind the audience. Then a few colored spotlights were added to enhance the visual aspect of the stage!

Quite naturally, the idea of placing an “orchestra” of loudspeakers came to mind. The different types of loudspeakers with different response and directivity curves, in addition to the filter modules, allowed for an “orchestration” of the diffusion. I have had very few opportunities to broadcast my works on these two systems (the Gmebophone and the Acousmonium), but my experience has remained the same: if the piece was composed with this type of diffusion in mind, it is likely that the results will be significant in simulating groups of loudspeakers as orchestral groups.

Otherwise, it would be necessary to have very long rehearsal times in order to produce a broadcast “score” corresponding to the device.

I will not get involved in the controversy between Christian Clozier and François Bayle over the chronology of these inventions and their exploitation. Wars and excessive “personalization” by studios and creative centers have done a great deal of harm to the public’s acceptance of electroacoustic music. Added to this is the exclusivity of national radio broadcasts, which are left to a single center (GRM), contributing to the marginalization of two or three generations of composers to the benefit of a chosen few.

This marginalization was compounded by that caused by the political “power” of Pierre Boulez and the structures he has put in place (IRCAM).

You studied under Messiaen (69) and then Schaeffer between 68 and 70. You took composition classes in Cologne and Darmstadt with Ligeti, Stockhausen, and Maderna. Can you tell us about their teaching methods? How did they influence you? What did you learn from them that you would like to share with our readers who didn’t have the same opportunity?

Let’s put things in order. I took Pierre Schaeffer’s classes at the CNSMD Paris from 1968 to 1970, as part of an internship at the GRM. After the events of May 1968 and the series of events celebrating 40 years of Musique Concrète, a wave of “revolt” forced these two institutions to open their doors wider for a seminar by Pierre Schaeffer (at the CNSMD) and for interns (at the GRM).

Of the nearly one hundred students enrolled in the first year, only about 20 remained in the second year with access to the GRM studios. The sessions at the CNSM (Berlioz Hall for those who knew the CNSMD on Rue de Madrid) led by the visionary Pierre Schaeffer were fascinating, as was the discovery of «Solfège de l’Objet Sonore» (Solfège of the Sound Object), which taught us to listen in a very different way and analyze sounds and music outside the traditional parameters of musical studies. At the end of the second year, five of us were commissioned to compose a piece. For my part, it was “Quadripôle Actif” in the 2-track version produced at Studio 54 of the GRM (located at the Centre Bourdan at the time), the most modern electronic studio in France at the time. The premiere took place in February 1971 in the last remaining building of the Halles de Baltard.

Starting in 1969, I took (still at the CNSM) the new course in Musical Analysis taught by composer Jean-Pierre Guezec, which offered a new way of approaching analysis, as Olivier Messiaen had done previously, from the perspective of a composer of our time. In my second year, in agreement with Jean-Pierre Guezec, I prepared an analysis of Pierre Boulez’s « Le Marteau sans Maître ». This was undoubtedly the first time that a work by Boulez had been included in the program for an end-of-year competition at the CNSMDP!

But Jean-Pierre Guezec died in February 1971. In order for the second-year students to be able to take their exams in June, Olivier Messiaen offered to take charge of this class for the rest of the school year. This is how I was able to attend several of his composition classes and, on several occasions, present the progress of my analysis work to Olivier Messiaen at his home and listen to his advice on how to prepare for the exam. In truth, I have few memories of the classes, because they focused on the work and drafts of the students in his composition class, and as outsiders, we felt a bit like voyeurs, which the “official” students also made us feel. On the other hand, the individual sessions at his home were very impressive and extremely useful in clarifying the presentations and, above all, simplifying the vision of a work whose complexity seems to be the primary criterion.

A few words about the courses in Darmstadt and Cologne with Ligeti and Stockhausen. In seminars of this kind, these “masters” talked about and sometimes analyzed one of their works that was scheduled to be performed in one of the concerts. For Stockhausen in Darmstadt, the students’ participation consisted of assisting the “Master” in the physical and technical realization of a work he was composing for the occasion (“Music for a House,” if memory serves me well).

In Cologne, during the period when I was traveling back and forth on the night train, Stockhausen was finishing the composition of « Aus den sieben Tagen » (an entirely verbal score) and experimenting with his ideas with the musicians/composers in his group. This was also the period of the first performances of “Stimmung” which allowed me to hear Stockhausen’s own analysis of the piece, followed by the premiere in Cologne and then in Paris shortly thereafter. As a student, this type of creative environment and concert preparation is very formative. You get to share in the experience up close, which is really very beneficial. I then had the opportunity to work for Stockhausen during the World Congress of Jeunesses Musicales, which took place in Paris at the Théâtre Renaud-Barrault in the Gare d’Orsay (long before it became a museum). I set up the technical equipment for a concert of his works using equipment from the International Center for Musical Research (CIRM) and the Schola Cantorum class. It took a whole night to set up the equipment, followed by rehearsals of “Chant des Adolescents,” “Stimmung,” etc. I was able to see that the “Maestro’s” demands were truly justified and that sound quality was his real concern.

I will always remember those 24 hours (without a break!) of working for and with him.

Since you mention Maderna, in Darmstadt, I took his conducting classes, which included Schoenberg’s «Pierrot Lunaire» and Boulez’s «Le Marteau sans Maître». His human and musical qualities are well known, and seeing him at work and explaining his gestures (in keeping with his physique) remain etched in my memory as great moments that, at the time, one cannot be fully aware of. Later, at the Royan Festival, I was the director of the installation for the broadcast of one of his works, and I was able to have one last contact with this truly extraordinary man.

How did you become familiar with/interested in electronic music?

My interest in electroacoustic music predates the situations I have just described.

Starting in September or October 1966, I took Jean-Etienne Marie’s course at the Schola Cantorum. The course was called “Musical Waveform Design, Applied Acoustics, and Analysis of Experimental Music.” This was quite a paradox for such a traditional institution as the Schola Cantorum!

After earning a high school diploma in mathematics and technology, a degree in general mathematics and physics from the Faculty of Sciences in Lille, and studying music in Roubaix, but above all, listening to many concerts, operas, and radio broadcasts, the title of this course was bound to appeal to me.

Though, my first contact with electroacoustic music dates back to 1958!

I visited the Brussels World’s Fair several times (we lived in Roubaix, 100 kilometers away), and I was able to see the Philips Pavilion designed by architect Le Corbusier. The entrance to this building was through a winding corridor (nicknamed “the stomach”) where visitors listened to “Concret PH” by Iannis Xenakis. Inside the pavilion itself, visitors were treated to a light show with images projected onto Edgar Varèse’s “Poème Electronique.” It was a shock I will never forget.

I owe a great deal to Jean-Etienne Marie because, in addition to teaching classes at the Schola every Saturday for four or five hours, he invited me to join him at the Maison de la Radio or at a concert hall where he worked as a broadcast engineer and also as a technical director for mixed works. This is how I was able to follow him throughout the conception of the French creation of Stockhausen’s “Mixtur” for orchestra and a very complex and delicate electroacoustic device at the Royan Festival in the spring of 1967.

From then on, my path was set.

How did you discover modular synthesis? When did that happen, and what did you think of it at the time?

At the end of my internship at the GRM from 1968 to 1970, I received my first commission for a ten-minute electroacoustic piece, which I was able to produce at Studio 54 at the GRM in Paris. I don’t think the studio was described as modular at the time, but in fact it consisted of a large number of “modules” with different functions, each of which could be used as a “producer” of sounds but also as a control voltage for each of the parameters of another module. Having had no opportunity to work in this studio again after February 1971, I only have partial memories of it, as studio time was naturally limited (usually in the evening until closing time around 11:30 p.m.!). However, I remember the need to adopt a “step-by-step” working discipline, very gradually learning how to use the parameter controls, because the result was very difficult to imagine, sometimes uncontrollable, but always delicate to reproduce.

What effect did this discovery have on your compositional process?

On your life?

How did it fit in with your other “compositional tricks”?

I believe that, without realizing it, I continued to compose my electroacoustic pieces, as I did in my early experiments with musique concrète, by using sound elements independently of one another and then applying the “mechanical” and “artisanal” processes of musique concrète to them.

I have often heard, and still hear today, about the results of a “simplistic” and “automatic” use of electronic modules that automatically generate changes over time.

Simply “letting the synthesizers run their course” is an easy solution that does not satisfy me. I need to create material and then work on it systematically. Like a sculptor, I want to be able to knead the sound material, shape it to my liking.

I always want to control the results and master my construction.

I don’t know if I’m making myself clear?

Absolutely, and I do share this attraction to an artisanal approach, to being a craftsman of sound.

You trained as an instrumentalist, so your compositional process is also based on the use of acoustic instruments, which you process or combine with electronic sounds. How did you work to integrate these electronic sounds into your acoustic material?

It’s true that mixed pieces have always been something of a trademark for me!

I’ve composed several ones where the electroacoustic device was “in real time” on the material itself, played live. In the days of tape recorders, ring modulators, and early synthesizers, concerts were sometimes a big risk. An AKS synthesizer had to be left on for several hours so that it would “respond” in the same way, the buttons had to be adjusted with millimeter precision, etc. But real time with analog devices allowed for very interesting work with the performers.

When it comes to my pieces for instruments and fixed sounds, it’s a question of sound material! I have a preconceived idea in my ear of the sound of the instrument, its timbre, its playing modes, etc. The electronic sounds that I am going to create and use are based on the timbres that I have in my ear, not to imitate or contradict them, but to find the “harmony” between a number of parameters for each one. The best examples in my work are “Hélicoïde” for piano in 1/16th tone by Julian Carrillo and fixed sounds, and “Bande de Moebius” for organ and fixed sounds. There is no attempt to imitate the sounds, but rather a search for concordance between certain parameters at each moment of the piece.

I often think that in the 1960s, and even in the 1970s, when electronics was still in its infancy, anything seemed possible. You can sense in the creative work of that period that composers allowed themselves to be surprised by novelty. Did it seem possible to invent at that time? What do you think?

Allow oneself to be surprised? Unfortunately, as I said earlier, too often, too many composers let the tap run dry!

At one point, “novelty” became a criterion for justification and quality. During this period, concert program notes were all written in the same way:

“this work is the first time this device has been used,” “…the first time this software was used,” etc…

I found this unbearable!

I am, of course, referring to the IRCAM concert programs from 1976 onwards, where all the works were so similar that they seemed to be by the same composer, made with the same sounds, the same timbres, the same rhythms!

Then, in the 1980s, a certain notion of control emerged, a desire for synthesis that would make it possible to remake the instruments of the orchestra. A desire for classicism? How did you experience that?

The problem with the 1980s and 1990s was the stranglehold that IRCAM and the Ensemble Intercontemporain had on what musical research should be and how music should be disseminated!

Yes, I don’t remember exactly when we started analyzing instrumental sounds, gradually modifying the parameters, then moving away from instrumental sound, only to return to it by finding the initial parameters. This principle could be interesting. So classicism? Perhaps!

Where do you usually start when you compose?

How do you see the relationship between sound and composition?

For me, composition is about working with sound material. Starting with sounds or short sequences whose timbres I like, I manipulate them like modeling clay, transforming them in every possible way to see how they fit together.

From there, I begin composing. The “form” of the piece then flows naturally from the treatment of the material. The “time” of the work then imposes itself on me.

This probably explains why, sometimes, the same material develops several times in different times: “Space Music I, II, and III,” “Elegy I (‘Aïka’), II, and III,” “Interferences I and II.”

To what extent did you strictly separate improvisation and composition?

I don’t improvise at all!

To tell the truth, I tried it once in a small group called “Opus” With Christian Clozier, Alain Savouret, Pierre Boeswillwald, and Jacques Lejeune. We did two or three concerts organized by the G.R.M. in foyer B of the Maison de la Radio, and then in Arras. I played a few notes on an old violin with a contact microphone and a large tam-tam. I must admit that I wasn’t very satisfied with the result.

Did you record directly without overdubbing, or did you end up doing multitrack recording and editing the tracks in post-production?

My working method has always remained very traditionally «handcrafted». That’s probably why I’ve never been satisfied with or even attracted to composing on a computer.

I naturally did an internship at IRCAM during the summer of 1979. At the time, it’s true that,- – technologically speaking – IRCAM, which had only been in existence for three or four years, was using machines and designs that were already obsolete! We would spend two or three hours in the evening writing hundreds or thousands of lines of code without hearing anything, only to listen to an unusable “splash-plouf” the next morning.

I need to hear the sounds and work with them.

What type of instrument would you prefer to play?

If I had seriously studied an instrument, I would have liked to learn the cello or the trombone, or even percussion.

Always low-pitched sounds!

You were clearly interested in gestures and physical movements as a means of creating music, weren’t you? What was your preferred way of achieving this kind of expression?

Listening to sounds, just listening to sounds!

Then analyzing those sounds, but outside of a manufacturing context. Then searching for similarities with other sounds and how they impose themselves and linger as if they were born from the gesture of a conductor.

From there, the sounds begin to live. And I can use them!

How can we avoid losing the spontaneity that analog instruments allow, which so many composers have lost since they started doing everything on their computers? In the studio, many people of your generation played standing up, which is very different from sitting down. What do you think about that?

It’s true, the work I just described can only be done standing up! You have to be ready to react at any moment so as not to miss the moment when something is supposed to happen.

With a computer, that’s impossible; that machine dictates the pace!

Building instruments can actually be similar to composing, in that you define your sound palette, with each new module or instrument enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that your choice of instruments and the way you build your playing systems are an integral part of your compositional process? Or is it the other way around, and were you looking for a new instrument because you wanted to be able to design the sound of some of your ideas?

In truth, anything is possible and all kinds of situations can arise. You can spend days on end searching for the sound you imagined, or rather the material you imagined and want to be able to work with.

And sometimes the situation is reversed, and you have to react very quickly to preserve that sound or sequence, while looking for a way to develop it in the right direction (or at least the direction you like at that moment).

In your opinion, what can only be achieved with modular synthesis and is impossible or more difficult to achieve with other forms of electronic music?

What I find characteristic, but no doubt that’s what I’m looking for, is the “thickness” and “harmonic richness” of modular synthesis.

I remember at the end of a concert, a young student came up to me and asked how I had created the sounds in that piece, exclaiming : “I can’t make sounds like that with my computer.”

That’s the unique feature of modular synthesis.

Did you feel close to other composers?

Which ones?

I regret not having known Varèse, but it is undoubtedly Xenakis’ personality that I feel closest to, even though we only had very sporadic contact and relations.

Which pioneers influenced you and why?

Edgar Varèse undoubtedly influenced me the most with his use of percussion. Then Iannis Xenakis for his use of mathematics. This led me to analyze his piece for solo cello (“Nomos Alpha”), an analysis that Xenakis partially reproduced in one of his theoretical works. I also had the opportunity to give lectures and courses based on this work, particularly when Xénakis asked me to replace him for one of his sessions at the École Pratique des Hautes Études.

Other pioneers? Julian Carrillo and his series of micro-interval pianos (from whole tones to 1/16th tones, the latter of which has enormous potential—it’s amazing!). Ivan Wyschnegradsky, too, for his use of quarter tones and micro-intervals in general.

Do you have any advice for those who want to get started?

It is very difficult and risky to give advice to young composers who want to get started in electroacoustic music.

There have been considerable changes over the past 60 years. Of course in cultural policies, but also naturally and above all in the tools, modes of creation, and dissemination.

The National Centers for Musical Creation (CNCM) were created from studios that emerged between 1970 and 1980. The link between research, creation, dissemination, and education made them public service structures for composers.

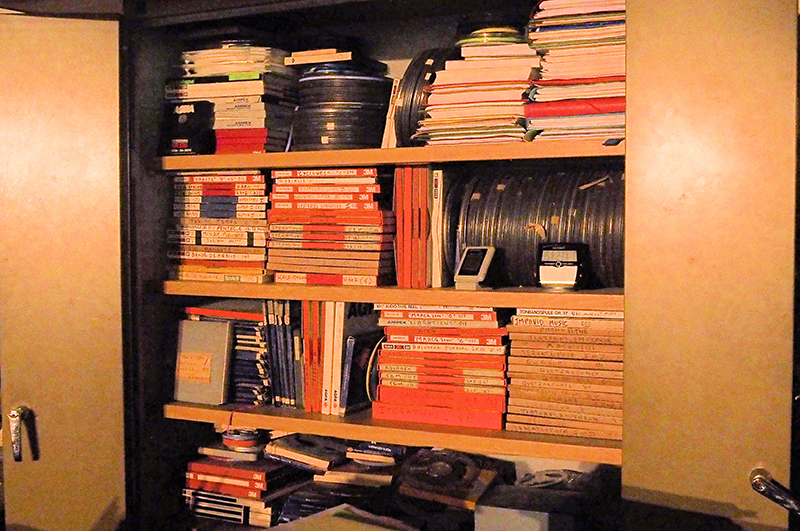

Composers at the time needed places with high-performance equipment and distribution solutions, because music publishers were not interested in studio productions. So studios were responsible not only for distributing their productions, but also for promoting them to music institutions and programmers. They were also responsible for storing and preserving the media.

The only two centers whose directors fully respected these missions, not only for their own productions but also for guest composers, have been closed: I am referring to the Groupe de Bourges (IMEB) (created in by Françoise Barrière and Christian Clozier in 1970) and the CIRM (initiated in nice, in 1978 by Jean-Etienne Marie), where national and local politics have taken over.

Technological advances have been so rapid that composers can now do much of their creative work at home. However, the problem of broadcasting has become critical for this music. Radio broadcasts are limited to a short hour around midnight on Sundays, but they are reserved for productions by a single organization, which poses a serious problem of fairness. Of course, platforms have been created, but their impact can only be very limited compared to the broadcasts of France Musique and especially France Culture between 1970 and 1990.

I can only advise young people to preserve their independence, of course, but at the risk of being recognized only marginally and belatedly…

https://www.fernand-vandenbogaerde-compositeur.fr