Wolfgang Seidel belongs to that constellation of German artists who, since the 1970s, have pushed electronic experimentation to its limits.

He is one of those sound engineers for whom the workshop is a laboratory,

the studio a darkroom,

and electronics an organism to be dissected.

He is one of those who have followed the path opened up by Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Kontakte:

sound as a physical phenomenon, not as a musical intention.

One could say that he is a sculptor of inaudible tensions,

someone for whom music only begins when the human ear begins to doubt what it hears.

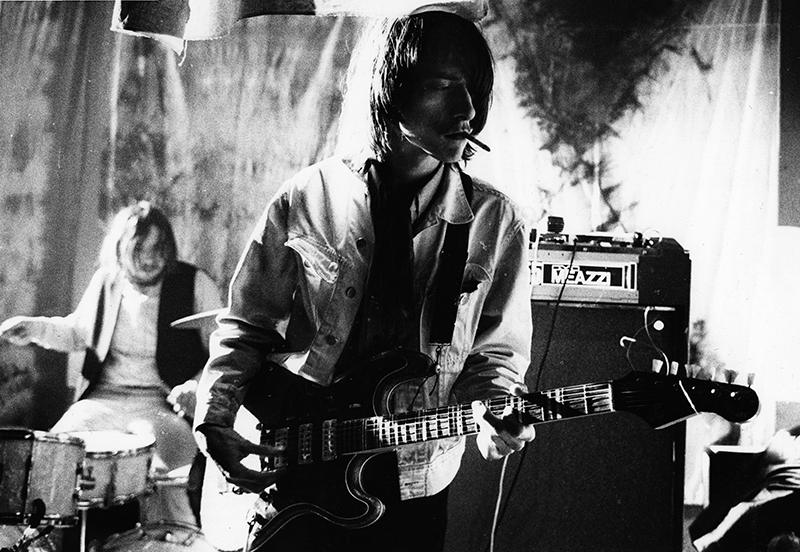

Fifty five years ago, amid burning pavement and rebellious walls, pounding the drums for Ton Steine Scherben with the fervor of a young meteor. But soon the rock battlefield grew too narrow, and he slipped sideways into another dimension, joining Conrad Schnitzler in the feverish laboratory of Eruption. There, he discovered the bright intoxication of pure sonic experiment.

That’s when he became Wolf Sequenza (nickname given by Conrad Schnitzler), the man who speaks the language of machines with a sly, delighted grin.

His albums with Schnitzler – Consequenz, Consequenz II, and the recently unearthed third chapter – are hypnotic corridors where sequencers pulse like mechanical hearts, each pattern opening a fresh crack in reality. It’s a rare kind of freedom, a nervous dance between geometric order and luminous chaos.

Time rolls on, Seidel keeps exploring:

improvisations, friendly synths, electronic whispers culminating in Friendly Electrons, where the machines seem to breathe right beside him.

To listen to Wolfgang Seidel is to follow the arc of a man who learned to sculpt electricity the way others sculpt clay.

A brief but blazing journey, traced by an artist convinced that at the end of every oscillation, another freedom is waiting.

You originated the cult improv band Populäre Mechanik in Berlin while being also friend with Conrad Scnitzler and thus in contact with Electronic Music, would you please retrace your career?

I started playing music in 1964. I was 15. I formed a band with some school friends. Only one of them had played the guitar a little before. I wanted to play the drums, but I didn’t have any. And I had never played them before. At first, I only had a snare drum and a small cymbal. The rest came gradually. We used old radios as amplifiers. But that’s how it was back then. Lots of enthusiasm. Our ‘music lessons’ consisted of standing in the front row when the local bands played. They were guys who were a few years older and had been playing for longer. We learned how each song went by watching. Due to our lack of English skills, the vocals were also a pretty loose interpretation of the original. We played at school parties and everyone had fun. The fun ended when we finished school. The band broke up and I sold my little drum kit and travelled to the south of France with the modest proceeds from the sale. That’s where the story would normally end.

Back in Berlin, an acquaintance approached me: he knew someone who wanted to start a band for a theatre group. They still needed a drummer. I used to play the drums. Would it be something for me? I replied that I missed music, but I didn’t even have an instrument anymore. That wouldn’t be a problem. The theatre group had one. So I was back in music again. After a year, the band began to break away from the theatre and go its own way. In 1971, they released their first single. Unlike other German bands at the time, the lyrics were not in English but in German. With this, the band – Ton Steine Scherben – had obviously found a gap in the market. The title of their first single is still quoted today: ‘Macht kaputt was euch kaputt macht’.

We rehearsed and recorded in an old ballroom that was also used by other bands. These included Tangerine Dream in their line-up at the time with Conrad Schnitzler. Not only did he have much more radical musical ideas, he was also not interested in having a permanent band with permanent members. So I found myself at his sessions – and had a lot to learn at first. He had no use for rock drums that played a straight rhythm from the beginning to the end of a song. Nor was he interested in repeatable songs. So I had a lot to learn. At that time, Conrad had left Tangerine Dream and Kluster. The sessions were held under the name Eruption. The name had actually been used for the first time for a huge jam session of the West Berlin scene at the turn of 1970/71. But for a while, it became the headline for Conrad’s activities, in which pretty much all musicians who could be classified as psychedelic and later Krautrock took part at some point.

In the 1980s, Conrad and I temporarily bid farewell to our free sounds and recorded songs. Or rather, parodies of songs. That was the time when the echo of British punk emerged in Germany as the ‘Neue Deutsche Welle’ (New German Wave). The result was the LP CON 3, released by Sky, with Conrad in the unusual role of singer. We got the commission for the LP thanks to an album we had recorded and produced ourselves in Conrad’s kitchen: Consequenz. The name was a combination of the first syllable of Conrad’s name and the nickname he had given me: Sequenza. After the release of CON 3, we released another LP as a sequel to Consequenz: Consequenz 2. On the second side of the album, we said goodbye to our foray into Neue Deutsche Welle and returned to the abstract sounds we love so much.

At the same time, I had started a band that took its name from the technology magazine I had read enthusiastically during my school days: Populäre Mechanik. This was the German edition of the US magazine Popular Mechanics. The German edition was a 1:1 translation of the original and, in a Germany where the traces of war were still visible, was actually more like science fiction. The members of the band had started making music in the 1960s, just like me, but then put it aside when it came to education, studies and careers. Punk and new wave brought new ideas and a new vigour. We were infected by it. However, as all the members of the band were already a bit older with careers and family commitments, it remained a leisure activity. Amateur status definitely has its advantages. You are independent and don’t have to worry about the commercial viability of the music you make.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

Over the past 20 years, Berlin has developed into a centre for improvised music.

Musicians come to the city for a short visit or stay for years. A whole range of clubs offer performances every evening. And many of the musicians visit me in my studio for sessions.

Recently, I’ve had a whole series of musicians from Asia – some with traditional instruments, some with classical instruments.

And occasionally, a performance follows. Although in recent years, I’ve rarely been heard with the same line-up.

So I can’t complain about boredom.

What do you usually start with when composing?

Most of what I do is improvisation.

Does that make me a composer? Yes.

Because improvisation is composition in real time. Alone or in a group.

I prefer working in a group. It’s most fun when you don’t know beforehand how the game will begin – and even less how it will end.

How do you see the relationship between sound and composition?

Composition is the temporal organisation of sounds.

To become a composition in the classical definition you have to put it down in a written score. Notating sound is difficult. Our musical notation is not designed for this purpose. One solution is graphic notation, but this leaves a lot of room for interpretation as to what exactly is meant.

Often, composition is less a means of defining the music than a means of upholding an idea of copyright, which is based on the printed score.

How strictly do you separate improvising and composing?

Most of the music I have recorded over the past 20 years is improvised.

You quickly learn that it makes little sense to start with a fixed idea. That might work for a solo, but it doesn’t work in a group because you can’t predict how the other musicians will react. And the unpredictable is actually the real fun. I have a few pieces that are compositions in the conventional sense. One example is Ton-Linie-Fläche, which was created for a finished film. Another example is Film Noir from the CD Friendly Electrons – a soundtrack to an imaginary film. But I knew that I would never have the chance to hear this music played by a real orchestra. I guess I had the ambition with this piece to prove to myself that I could do it.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

The recordings of group improvisations are always live, without overdubs. The recordings I make on my own are not actually intended for release. I try things out. The purpose of the recording is to check which ideas are worth pursuing further. Sometimes, when I listen to it afterwards, it turns out that such a recording is quite presentable. Then I might refine the result with one or two overdubs. Or I use the collage technique I learned from Conrad Schnitzler and play two independently created recordings simultaneously – sometimes with astonishing results. Post-production only takes place to the extent that it is usually necessary to shorten the recordings. With the collage technique, collisions sometimes occur, and then I have to reach for the scissors.

What type of instrument do you prefer to play?

Since my synthesizer offers a wider range of sounds, I spend more time with it.

In a group improvisation, it depends on which instruments my fellow musicians are using. If they are rather quiet, I concentrate on electronic sounds, as I can control the volume better that way. But drums can also be quiet. It’s usually a spontaneous decision. That’s how it is for the sessions in my studio. It’s different at concerts. I have to decide in advance because I can only transport either the drums or the electronics and accessories. I’m rarely lucky enough to have the venue take care of the transport.

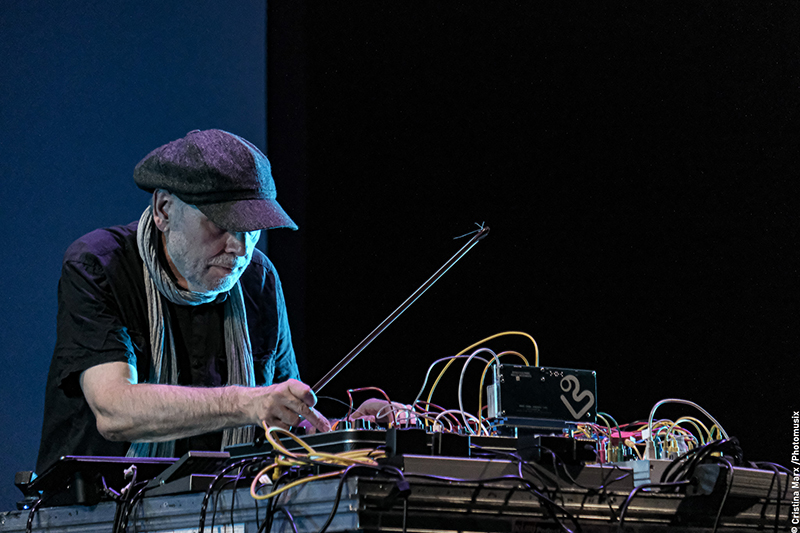

Obviously you are interested in gesture, physical move to create the music, right? What is your favorite way to achieve such expression?

With drums, it’s very simple because movement and the musical result are directly linked. Firstly, it’s fun. And secondly, it makes it easy for the audience to connect what they see to what they hear. I think that’s important for communicating music. And why should an audience stare at the stage if there’s nothing to see? When I perform with my synthesiser, it’s a bit more difficult (for those who really want to know: a Buchla Music Easel). Sometimes you have to exaggerate your movements a little. And my equipment includes a lap steel guitar. I’ve had it since the days of Conrad Schnitzler’s Eruption. For me, it’s a percussion instrument. And again, the connection between sound and movement is directly linked for the audience.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

In recent weeks, I have had visitors from Asia – Taiwan, South Korea, Japan. Some brought traditional instruments such as the suona or sheng, others brought cellos, pianos or double basses. Apart from these sessions in my studio, there is nothing else in my calendar at the moment.

To be honest, the sessions in my studio are more important to me than public performances.

Your compositional process is also based upon the use of acoustic instruments that you process or combine with Electronic. How do you work to marry that Electronic with your acoustic matiere?

When I play concerts, I decide in advance whether I will go on stage as a drummer or synthesist. Both require too much organisational effort. For sessions in my studio, both are set up: the drums and the electronics. But most of the time, Sometimes I don’t even have to decide, because there is another drummer present. The acoustic instruments – drums, strings, wind instruments – remain as they are. Musicians playing improvisational music have developed so many advanced playing techniques that can be used to alter the sound of the instruments that there is no need for additional effects.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

How does it marry with your other ”compositional tricks”?

I got my first synthesiser in the 1980s.

Before that, I only had my drum kit. A drumkit is sort of modular.

The synthesizer was an EMS Synthi A. It doesn’t have a keyboard, but that didn’t bother me. I didn’t want to play conventional melodies that just sounded a little different. The Synthi A is wonderful for drones. I had enough percussive sounds from the drums. The Synthi A is a modular system, only with a patchbay instead of cables.

Later I added a Sequential Pro One. I thought I also needed a keyboard on which I could play melodies. But the two Consequenz albums with Conrad remained the only occasion where I needed it.

Ten years ago, I learned that the Buchla Music Easel was being built again. It’s pretty spartan in terms of features, but it’s very spontaneous to use and wonderful for percussive sounds. Like the EMS, it’s built into a case and so easy to transport. Since carrying both its too much to transport, I carry the EMS with me in the form of samples stored in a small sample player. I also have a Nord Micro Modular. It fits easily into my bag.

When did you buy your first system?

What was your first module or system?

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

About 20 years ago, I bought a used Analogue Systems modular system.

It’s easy to explain why I bought it. The modules are inspired by the old EMS – but with patch cables instead of the Synthi A’s matrix. Later, I added a second frame and a few modules: a Make Noise Maths and, from the same company, the Wogglebug. Math is a variation of the EMS Trapezoid Generator, and the Wogglebug is a random generator, which I always missed on the Synthi A.

A few other modules followed, including some that didn’t add much musically. And I then learned that more modules become more of a hindrance when playing live. When playing live – whether in front of an audience or during a session in my studio – every idea has to be quickly implementable. Too many modules are just ballast.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

The step from percussion instruments to electronics is not that big. At least not if you haven’t only been involved with rock drums. But I played in an ensemble for a while, where I encountered contemporary percussion music. There you learn to understand music as the temporal organisation of sounds – musical and non-musical, or noise. Electronics ‘only’ brought an expansion of the tonal possibilities. In terms of composition, it makes little difference whether I use a noise generator or a snare drum with jazz brushes. For the snare drum variant, you don’t need a power outlet or speakers…

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? You owning an impressive amount of gear, how do you explain that?

Since playing live is my main focus – whether on stage or in sessions – there is a limit to how much sense it makes to keep buying modules or instruments.

However, I did stray from this realisation once. That was when all the clubs were closed due to the covid restrictions and I was sitting alone in my studio. I consoled myself with modules I ordered online. And I had no choice but to record solo. However, I benefited from the experience and musical vocabulary I had learned in many sessions. During the solo recordings, I played with an imaginary partner. Now musical life is back to normal and what I bought during lockdown is now sitting around gathering dust.

Do you prefer single-maker systems, knowing your love for BugBrand or Metasonix, or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs?

How has your system been evolving?

My start in the modular world was with an Analogue Systems.

Then I added a used Eurorack system with a Livewire Audio Frequency Generator and a double LFO from the same company. I also got a Make Noise Woggle Bug. That would have been enough but I bought a few more modules, only to realise that I didn’t need them.

Only the Maths from Make Noise, a VCO (Synthesis Technologies Morphing Terrarium) and a Turing machine stayed. And because I love a pure sine wave, I added a Quadrature Thru Zero oscillator from Doepfer What was still missing?

A keyboard? No. When I want to play conventional melodies/chords, I use my 1970s Yamaha combo organ. For the modular system, I use the Doepfer Ribbon Controller. One? Two are twice the fun.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

When I started putting together a modular system, I thought I needed every module in the world. Then I realised that completely different things were important to me. In collective improvisation, which is my field, the most important thing is to be able to react quickly whenever the music takes a new direction. Neither your fellow musicians nor the audience will wait while you rearrange your cables and fiddle with all the knobs. I currently have two setups to choose from. One consists of the Music Easel, a Nord Micro Modular and a sample player. The other setup is my 60-year-old Yamaha organ. With that, everything sounds like 60s psychedelic or early Krautrock. There’s still room on top for a row of modules and the ribbon controller. The modules are the Synthesis Technoly Morphing Terrarium and, from Tip Top Audio, a Buchla oscillator and a function generator. Plus a low-pass gate from Make Noise. That’s enough for my purposes.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

From the early days of Krautrock, I still have a Dynacord Echocord tape echo – the one with the sliding tone head.

But it’s too big and heavy for live performances. So I use a small stompbox. I also use a phaser for the organ.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

Almost all of the recordings for the Modulisme Session are less than a year old.

They were all created using the two setups I described.

Either with one of the setups, or with an overdub, where I switched from one workstation to the other. That helped me to act as if two musicians were playing a duo.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

The two setups invite you to record an overdub. But anything more than that is the exception. For that, I like to use the third workstation, which I forgot to mention: the drums.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

I have a default setting where I can switch between two very different oscillators (Morphing Terrarium and Tip Top Buchla) with a single movement. One is for percussive sounds, the other for modulated drones.

Which module could you not do without, or which module do you you use the most in every patch?

The Easel is what it is. Mine has an additional oscillator. But that’s it. And my small modular system is so economical that I can’t do without anything extra. There’s no room to expand it either. It has to fit on the free strip on the organ. The fact that I can’t expand it has a pleasant side effect: it saves money.

w/ Hans Joachim Irmler, Alfred 23 Harth, Günter Müller

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

My role models are the pioneers of electronic music from the 1960s.

They didn’t want electronic sounds to imitate strings or pianos. That also included completely different compositional approaches. These musicians didn’t have much more than a sine wave generator, a filter, a tape recorder and a pair of scissors.

If you want to follow in their footsteps, you don’t need much more than that today either. But you can put the scissors aside. With digital recording and editing technology, you can achieve your goal much more quickly and comfortably.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

When I dream, it’s about what I can do with the instruments I have.

Or I dream about which musicians I can invite to a session. The latter brings more change than a new module.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Which ones?

The first two musicians that come to mind are Richard Scott and Eliad Wagner, who can often be heard playing in Berlin. Both are improvisers who play in different contexts and with different ensembles.

Eric Bauer also belongs to this scene, performing minimalist pieces in a duo with trumpeter Carina Khorkhordina.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

The classic line-up: Stockhausen, Riedl, Xenakis, Subotnick.

And then there’s a duo that was my first encounter with abstract electronic sounds: Bebe and Louis Barron and their soundtrack for the science fiction film Forbidden Planet. When I saw the film at the end of the 1950s as a schoolchild, I knew what the future would sound like.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Start with just a few modules.

Fortunately, the days of having to invest a lot of money are over. Owners of expensive collector’s items won’t be happy to hear this, but today there are inexpensive replicas of the modules from the pioneering days of electronic music.

Of course start playing with other musicians as soon as possible.

Those who only ever tinker with their modules on their own will end up alone.

https://www.ventil-verlag.de/titel/1966/krautrock-eruption