Jobina Tinnemans is a Dutch composer whose work bridges science, orchestral writing, and modular synthesis with striking force. Drawing on seismic and astrophysical data, she builds vast sonic architectures for orchestra, organ, and electronics that feel both monumental and alive. Her music translates invisible phenomena into immersive, physical experience ; expanding how contemporary composition engages with scale, system, and sensation.

A singular voice in experimental and orchestral music, she turns data into resonance, and structure into impact.

Jobina Tinnemans composes from phenomena.

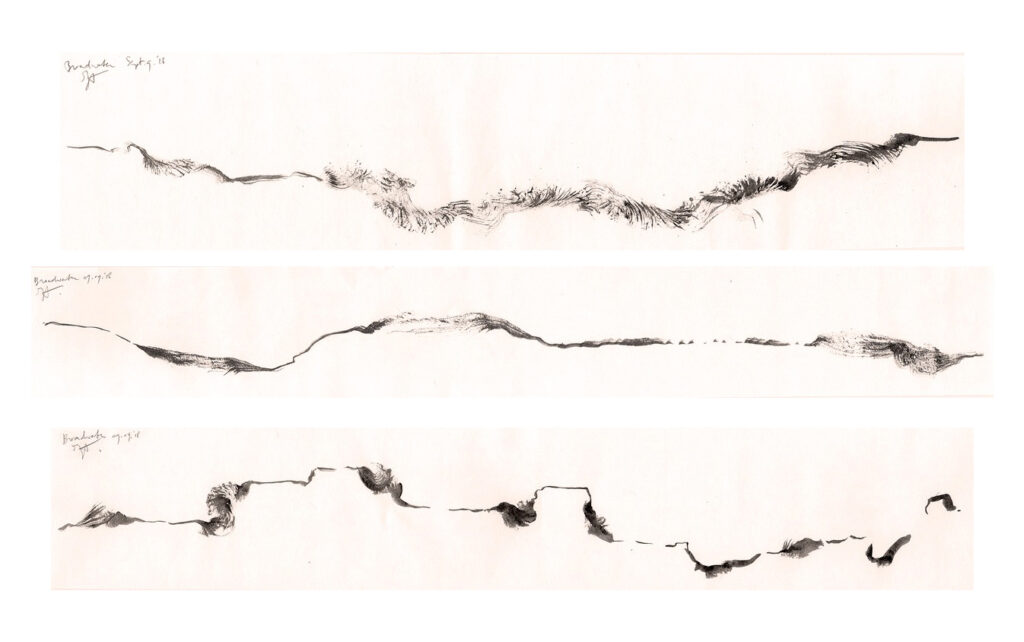

Her works often originate in scientific data: seismic recordings, astrophysical dynamics, natural structures translated into sonic organization. These data become temporal matrices, that shape the form and her composing reveals their behaviors, their densities.

Textures thicken and shift. Time acts as a ductile material: sound masses being stretched, compressed.

Each piece seems to evolve according to its own internal logic, like a system that breathes.

The organ long occupied a decisive place in her exploration. An architectural instrument which engages the entire space. Low registers move air with tangible physical force. Harmonic combinations generate vibratory interferences that turn listening into a bodily experience.

Her work with modular systems privileges continuity and internal transformation. A network of oscillators, filters, cross-modulations, and feedback loops, forms a behavioral terrain.

Interactions generate microtonal drifts, unstable pulsations, progressive accumulations.

Low frequencies establish a vibratory foundation. Upper spectra open zones of expansion. Modulations create tensions that circulate through the sonic matter.

Listening becomes almost tactile.

Scale remains a central axis.

The invoked phenomena – geological, cosmic, atmospheric – find perceptible translation at a human scale.

A few minutes concentrate dynamics that originally unfold across immense durations.

Her music functions as a device for translating scale.

In this work, structure and sensation move together. Systems generate complex forms; sound engages the body.

Vibratory fields alter the perception of space. Accumulations create a pressure felt as much as heard.

Jobina Tinnemans thus develops a music of phenomena: a music of mass, tension, and emergence.

A music in which systems become perceptible, and vibration reveals the magnitude of the world.

Before they became flat-pack audio files to be assembled in your imagination, the music on this release physically existed in the cavernous spaces of the rapidly changing soundscape of our times.

They were triggered by the many buildings and environments that I have inhabited, by the people I worked with, and by the technological developments that were new and exciting as the years passed by.

These works are the diary, describing little capsules of time in far more colour and detail than words could ever do.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

I used an ARP2500, ARP2600, VCS3, Korg MS20, Hammond organs and a plethora of other cellotaped organs, various modified high-voltage health and safety hazards, as well as field recordings, custom-made DAW with custom hardware and acoustic instruments.

When Diary II 2015-2025 is released, later this year, the double album will be published with diary entries for each track: where I was, what instrumentation, which project I was working on.

That’s also when I will make a short-run of physical copies available via my label Article Music in the shape of a diary book, to accompany your online Modulisme release.

The two diary albums take us through twenty years of configurations and reconfigurations of musical gear, working sometimes with, sometimes against the tide of technological developments. In those two decades I lived in many places and moved between countries, every change reflected in the set-ups of my studio and the resulting sound it generated.

Would you please retrace your career?

In the student flat next door to mine, a friend was selling her electric guitar.

I was moving on from my piano – and ballet – centered childhood and realized that the time had come to summon my inner Sonic-Youth.

But soon the distortion and jack leads came to interest much more than the fake Fender, its pedal sounding so much better when I hooked it up to an electric organ. Word got round and in the next few years, around the turn of the century, more lonely organs came to live with me. At some point I found myself in a disused office block, once home to Philips Electronics, in a hallway of about twenty rooms centered around a very – very – long extension lead, with a different organ propped up behind every door – several Hammond organs, an Eminent, a Yamaha, a Crumar with accordion buttons instead of keys – like some sort of curious advent calendar.

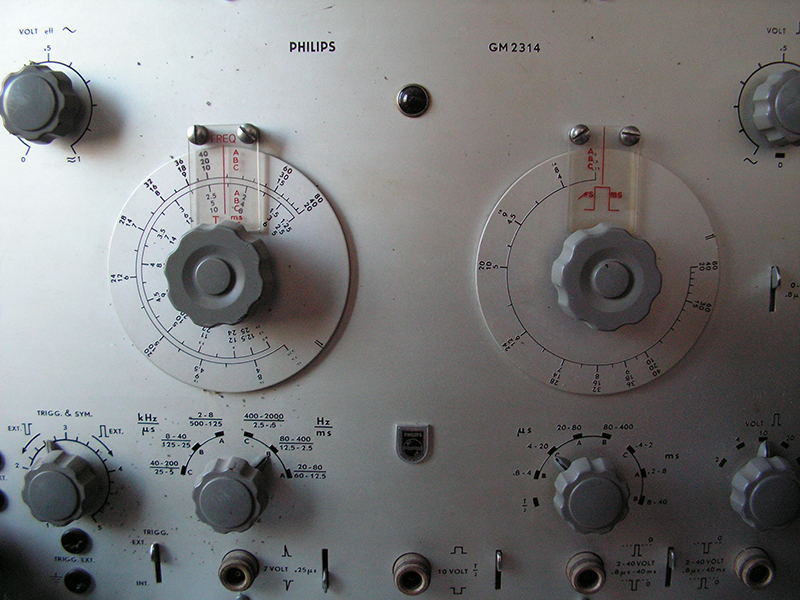

These were all patched with FX racks, such as the Yamaha REX50 and SPX2000, some stand-alone units and reel-to-reel tape recorders. Lots of this gear I had fished out of skips or found at flea markets: I was living in Eindhoven in the 90s and 00s, at the dawn of the digital era, and former employees of Philips Electronics were clearing out garages and attics full of stuff developed or produced at their work in the 1950-80s. Then I took it for granted, but now I understand that finding so much gear in skips and charity shops was in fact the result of a unique set of parameters.

After 2000 I made both abstract pieces and songs, the latter under the stage-name BLATNOVA.

To play my concerts I had to shove an organ or three into the back of a little van. Even with the help of some wheels and a rickety skateboard this was heavy lifting, so after a while I began disassembling the organs to access their separate components and modules. These I refitted in lightweight cardboard boxes, before combining them into a single piece of organ furniture: a rather cumbersome organ-shaped flight-case.

On stage it looked as if I was performing my entire set on one crappy little organ, which amused me no end and bewildered my audience.

How were you first acquainted with Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

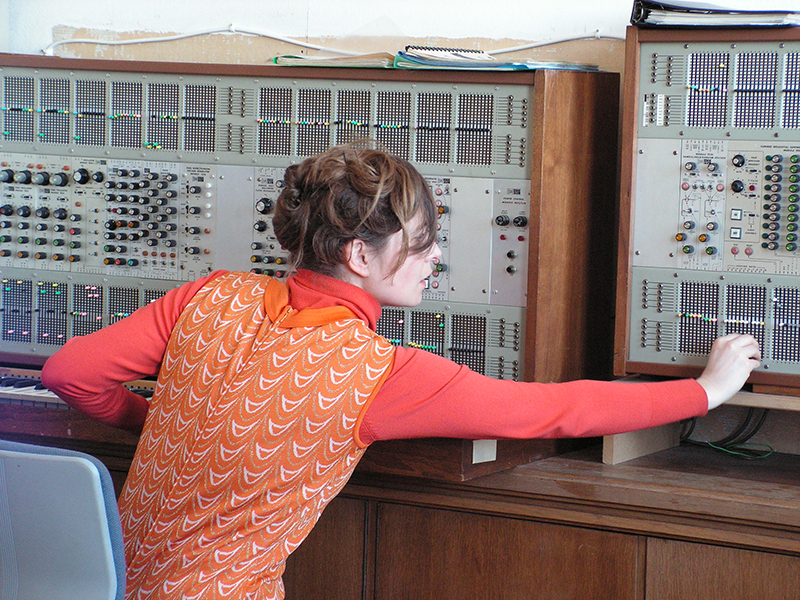

In 2006 I was invited for a residency at the Worm studio in Rotterdam where I met the ARP2500 with sequencer, as well as the EMS VCS3 and grey metal boxes with not much more explanation on them beyond the familiar Philips logo.

Without a manual it took some figuring out to get the ARP to make a sound, but I adored the matrix switches and the way you could keep track of your progress throughout the machine.

I haven’t encountered that particular crunch and intensity of the ARP2500 anywhere else. Pinpoint precision.

Soon afterwards I acquired my Korg MS20, which felt pocket-size, a slightly unfounded worry whether it could be ‘too light to be right’, next to all the other gear.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

I eventually moved to a remote peninsula in Wales in 2007 to focus on music-making and seven of these organs and the MS20, boxes full of organ bits, all modules and FX processors, a prepared piano, an Atari 1080 with external HD (with a whopping 20MB capacity?) samplers, synths, mics, reel tapes, DCC recorders and a very large crate of leads in every (antiquated and obsolete) specification and size made it into a large van. I had no idea what I was getting myself into, but it was life-changing.

Storms, crashing sea waves, impenetrable darkness and seasonal shifts. Oystercatchers, seals, migrating and local wildlife; pebbles, boulders, rocks, cliffs and echoes: hooting, booming, whispering silences and textural densities. This wasn’t the electronic pop culture I was familiar with. For decades I had listened to a host of innovative and/or vanishing media carriers, from vinyl to cassettes, open-reel tape, MDs, DCCs, CDs, RAM DVDs, ZIP drives, MP3s and, eventually, via streaming, but now I was experiencing a soundworld by simply walking around.

Inevitably, the dynamics and textures I was now listening to, in surround sound, started to find their way into my music.

The biggest challenge was to make something meaningful from my immersive muse, the natural soundscape, when the original sounded so good. Playing around with natural sound textures and timing became the main drive of my creative process, until I was happy to incorporate these slippery forces into my compositions, which is what I’m doing now. Learning never really stops and the wonderful sonic coincidences of a soundscape never ceases to surprise. This is where the similarities with modular synthesis come in. In my mind I play with each module representing another aspect of a biotope which is minding its own business, and together they create a sonic space to exist in.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming performances?

After the release of Electronics Diary II, 2015-2025 later this year, I will be releasing an album with works made on an ARP2500 and a Subharchord, then a Nordic Noir-inspired album in mixed acoustics and electronics, and an album with piano works called Riley, inspired by Bridget Riley’s artwork.

A long-term production I’m working on is an opera called A Hundred Thousand Good Nights based on letters from 1664 that never reached their destination. I transcribed the letters from old-Dutch as part of a university project and they tell incredibly moving life-stories. As the first person to read these deeply personal letters I feel a responsibility to let our ancestors’ be heard in this opera.

It’s been a while since I performed live with the projects I’ve been working on, but I might take it up again, who knows?

Your compositional process is also based upon the use of acoustic instruments that you process or combine with electronics. How do you work, to marry that electronic with your acoustic matière?

Acoustic or electronic, everything is sound, so it is all of equal interest to me and both disciplines feed into one another.

While working in electronics and effects processing – which feels instant and intuitive in both listening and responding – I like to contrast it with acoustic processes – often presenting itself in a meticulously detailed undertaking, challenged by physical restraints of instruments and performers – and vice versa.

Nevertheless, the sonic languages themselves have much in common.

Once you have the fluency you can run through the sound library that you’ve built up in your mind and hear how it all fits together. It’s an exciting pairing of sound worlds.

What do you usually start with, when composing?

It starts with a shape in my mind, although it’s more an awareness than a shape.

All I need to do is to realise it, but there are many distractions on the way. It’s easy to think something else might work, but usually the result is not satisfying – a bit like trying to get to Middle-Earth.

I still waste time trying things, only to come back to what the initial feeling was. It’s all about instinct.

How do you see the relationship between sound and composition?

Sound is transmitted energy.

A sound needs its own space to travel in, then listening needs space for the sum of all these energies to settle.

The two combined make a composition.

In my classical compositions I make sure performers get enough physical space to generate the energy they need to create the best sound. It’s like the visual arts disciplines: the blank, the empty, the rest or the silence, are just as important as the material.

How strictly do you separate improvising and composing?

An improvisation can feed into a composition and a composition into an improvisation, and yet they are still completely separate beings. To me, an improvisation is about the performer and a composition is about the listener.

What type of instrument do you prefer to play?

My studio is a shape-shifting instrument in its totality.

As a classical pianist I tend to move towards keys, but life is even better if there are faders, knobs and switches (and lots of cables) involved. The mixing desk is also an instrument, often overlooked but very versatile in its own right. I use little ones, 6 to 8 channels, to create a palette of sounds from various machines, extending the sound world with the invisible spectre of feedback.

Obviously you are interested in gesture, physical movements to create the music, right? What is your favorite way to achieve such expression?

This started fairly light-heartedly in 2007.

I felt the need to loosen up my music writing and dreamt up ways of creating works where the sound was a byproduct of something else, just to experiment how it would sound and to get a different sense of timing.

I could have used randomisers or, indeed, many other ways to do this, but it is more fun to rustle up some friends to do a sport activity as an act of modular synth embodiment, generating high pitched sonic textures made by squeaky shoes on a leisure centre floor.

Or what about sequencers made of ping pong balls hitting the bats and tables?

Feeding these sounds through a set of sound processor patches would complete the composition.

The Diary I & II albums include some of these works.

How can one avoid losing the spontaneity that the analogue instrument allows and that so many composers have lost since they do everything from their computer? The click of the mouse doesn’t sound like the turn of a knob, does it? How does it marry with your other « compositional tricks »?

Even though a click of a mouse is in itself a controller, the act of playing an instrument with a tangible physicality, whether electronic or acoustic, is not only about time or timbre, it is both an entire phenomenon and also all that it is not: all its limitations. This is the opposite of the ‘limitless’ experience that a DAW sees to offer.

The majority of the organs I owned, for example, didn’t really sound great. It took a lot of effort to make them more interesting by patching them into a host of other ingredients.

Other parameters, such as not having enough hands to control all the knobs and patches, create their own particular time-flow.

Or a feedback doesn’t sound as you intended because you used a different cable, or you get annoyed because you didn’t press record and want to retrace the settings (which never works), or a sequencer speeds up as it gets warmer and throws everything else out of synch, or instruments are out of tune and generate dissonances, or you just need to take a breath.

All this is wonderful.

Of course you can make your DAW experience less accommodating too: just add trouble. But I’ve never heard any sound or distortion from a DAW vibrating as deep into your body as analogue electronics do, and it’s that vibration that leads to a very different sort of musical decision-making. Perhaps the most significant filter of all, however, is not in VCO or LFO panpots but in the mindset of the people that love working with them.

Which pioneers influenced you and why?

When I started out in the early nineties I was intrigued by the 1950s researchers-in-white-lab-coats era of sound experimentation at the Philips Electronics’ physics lab run by Dick Raaijmakers (Kid Baltan), Tom Dissevelt and others, in Eindhoven where I lived at the time. This petri-dish approach to synthesized sound-making was often truly abstract, at times compositionally on a par with the pragmatism of a car dashboard design, a product of circumstance.

I liked how it didn’t try to be something else.

Early on I also came across Arp Art (1972) by Elias Tanenbaum, New Sounds In Electronic Music (1967) and Eight Electronic Pieces (1961) by Tod Dockstader, which all had a quality of abstraction that feels like a work of architecture. The second album features a tape work by Steve Reich, which reminds me of how close the classical and electronic music worlds were at the time and just how far apart they seem to be these days.

And Morton Subotnick’s set of Electronic Works and so many more.

From this very short list you can see that in the nineties I never came across recordings by women, nor any fellow sisters making electronic music. It was kind of hit and miss what one would have access to, although this changed with the arrival of the internet.

It also had the psychological effect of making me hesitant about releasing my music, so it’s nice to get things out there.

Modular electronics cover so many music genres that I haven’t even touched on the rhythm and beats side, but Venetian Snares is a long favourite. Aaron has a certain ‘Wehmut’ that’s always there in his work and hits a spot, perhaps also because his almost out of control dense layering of beats connects to my technique of cranking up the tempo of the rhythm boxes on the organs I owned.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists or composers? Which ones?

Caterina Barbieri’s Vertical (2013) in which she explores sinus waves is gorgeous.

In earlier publications of Modulisme I’ve come across some artists that are new to me (thank you!), I’ve been thoroughly enjoying Ocean Viva Silver (Valérie Vivancos) minimalist album Hal Saflieni (2022), full of elemental textures.

Rie Nakajima’s Dead Plants & Living Objects (2020) takes modularity to a next level with her kinetic objects, but the spirit of her work fits in with minimalist modular electronics.

To see her perform live is an experience.

Jocy de Oliveira’s absurdist rich worlds of Fata Morgana (1987) and Inori (1993) very successfully combine classical instrumentation and voice with electronics and have been around for a while, as well as the music by Else Marie Pade, who’s entire body of work I find glorious, starting with the remarkable Syv Cirkler (1958).

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Even though I’ve been commissioned to do incredible projects in the last two decades, I’ve struggled to believe in myself.

This can be true for anyone and for all sorts of reasons, but don’t let it stop you.

Take what is available to you and make it work, because: there are always more synths on the horizon.

Sometimes it feels like you are building towards the perfect set-up and then you might have to let it all go again. That’s fine, too.

Choose to see everything as a step towards the next thing.

Oh, and read the manuals.

Tom Robinson, well-known from his pop songs and a celebrated BBC radio DJ made this video for the track Midshipman & Mermaid :