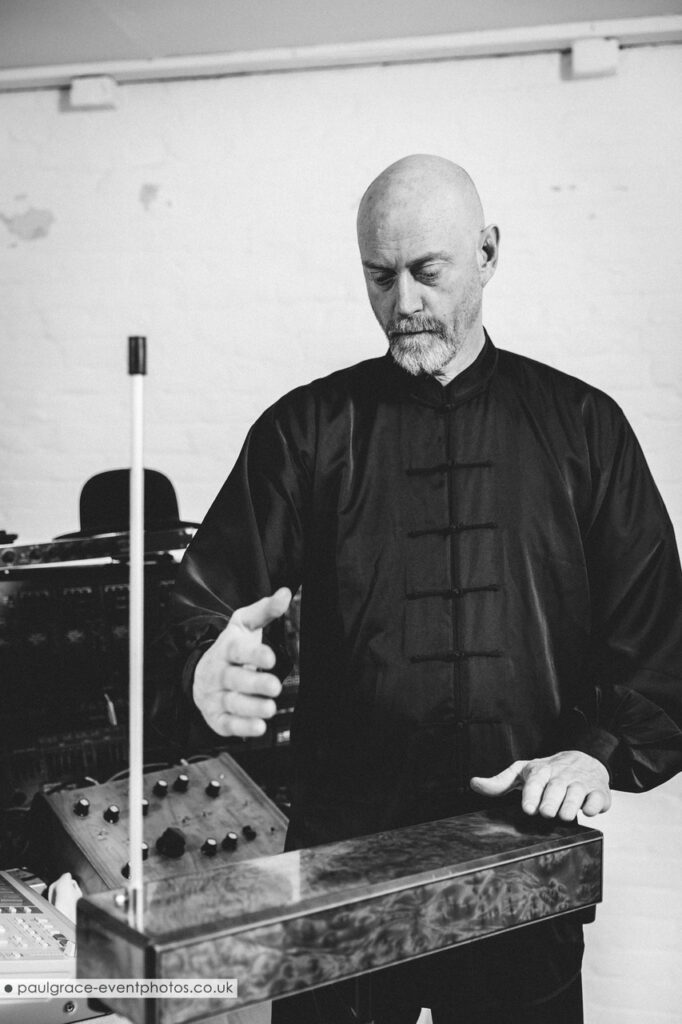

Jono Podmore has been a musician for over 40 years! Started in bands and orchestras as a kid before moving to London to study Electronic Music. Then from playing in bands ended up gravitating to production, engineering, programming and string arrangements in the 80’s/90’s and then started releasing his own material under the name Kumo. In ’97 he went to live in France to work with Irmin Schmidt on film scores, his opera Gormenghast, the Can archive and new material.

Jono was appointed Professor of the Practice of Popular Music at the Musikhochschule in Cologne in 2005 where he still runs the MA Production course. After moving back to London he set up Metamono; a purely analogue, modular, electronic band… After the death of drummer Jaki Liebezeit in 2017 he worked with his fellow drummers, collaborators and family to write and edit a book based around his rhythm theory in the context of his life’s work. “Jaki Liebezeit, The Life, Theory and Practice of a Master Drummer”.

Jono is writing the score for a feature film of “The Giaour”, a retelling of Byron’s epic poem with some very exciting musical collaborations. Recently he released “Hallraum” with Swantje Lichtenstein on seminal cassette label Tapeworm, and appeared on “New Clockwork Music”, a double vinyl set of music inspired by Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis?

The keyboard player in a band I was in when I was a teenager managed to get a Korg MS-20 which fascinated me, especially patching in external sources. Later when I got to university I was immediately fascinated with the handful of VCS-3s that were lying around rather unloved in music department. What I learned then I still work with today.

When did that happen? When did you buy your first system?

I started with a modular approach to synthesis well before Eurorack appeared. I got my Arp 2600 in 95 and was working with controlling it with my theremin via CV and gate, so when I first saw a Doepfer A100 in Switzerland in ’96 I was intrigued rather than overwhelmed.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

It was a gentle affirmation of what had always interested me and of my working method. I was never a keyboard player (I was trained as a violinist) so synths for me were limited by the keyboard: it made them into little more than Hammond organs. Imagining sounds and musical structures then seeking to realize them by bringing forces together on their own merit, rather than grabbing sounds out of a box and playing the same old keyboard part with them was always my approach.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied?

How do you explain that?

There are a few things. The genius of the eurorack and the 500 rack systems is that they make modules more affordable as you’ve paid for the power supply already: it’s in the rack. For product development the power supply is the most difficult part as that’s where all the safety regulations need to be fulfilled. Without those concerns it’s easier and quicker to bring out funky new products more cheaply. So that gap in the rack that is crying out to be filled can be filled without breaking the bank. The market for music tech is filled boys and men with the same completist, hoarding hunger that exists with photography or even record collecting, so a system that has created a steady flow of new and affordable products is pure temptation to these guys. Sadly a full rack does not make you a composer, as most of them are finding out… but maybe that new hardware sequencer will sort that out for them…

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Arp 2600, Roland MC 202, Handmade “Longwave” Theremin, Handmade “Lili” Ring Mod/Filter/2xLFO unit, Eurorack with Expert Sleepers Disting, Intellijel Planar 2, Delta Saber; Doepfer MCV4, Korg Minlogue, 500 rack with Elysia Xfliter 500, IGS S-type compressor, 2x Fredenstein pre-amps; MXR carbon copy delay, RME fireface interface and AVID pro tools.

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

The session consists of a number of pieces, some live, some studio from the last couple of months. Mostly I tend to use a different patch to create each individual sound, improvise with it, and then record, although I also create complex multi timbral patches for live shows.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

To be honest, I find that when you have all the toys you could possibly want, you run out of ideas. One of the creative forces of Metamono was how the restrictions we put on ourselves forced us to be more creative with the music, the content itself. I dream of a system that forces creativity, but maintains lasting technical quality.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Paul Conboy and Mark Hill of course, the other 2/3 of Metamono.

Ian Tregoning and I have worked very closely over the last couple of years, his eurorack system is most impressive now.

Dan and Reuben from Sculpture are a constant source of inspiration.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

My big influences are electronic music giants from over 7 decades now: Stockhausen, Takemitsu, Parmegiani, Bayle, Bob Ostertag, Suzanne Ciani, Pansonic, Martin Rev, Holger Czukay, Richard Kirk…

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme”?

Concentrate on the content, the ideas in the music itself, and then find a way to realise this with whatever technology you have to hand. That’s where to focus the imagination and ask questions. Then keep your ears open and let the instruments bring new flavours to the table.