André Stordeur was born in 1941 and started playing Be Bop/Hard Bop with John van Rymenant in the late Fifties, drumming along Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Nina Simone while working for Pan American World Airwaves and thus travelling the world and being exposed to many shows or cultures, most notably at Village Vanguard New York. He then learnt Tablas/Sitar in India, Percussions in Thailand and throughout those first years moved on playing vibraphone, métallophone and Contemporary Music…

In 1973 he participated to avantgarde music ensemble Studio voor Experimentele Muziek, founded in Antwerp, Flanders, by Joris De Laet. S.E.M.’s associate composers included: Dirk Veulemans, Paul Adriaenssens, Karel Goeyvaerts, Lucien Goethals and Serge Verstockt. In parallel Stordeur founded his own « Studio Synthèse » in 1973 in Brussels where he was teaching and experimenting, mostly on a Synthi AKS.

In 1979, he collaborated with Paul-Baudouin Michel on an electroacoustic music composition titled «Phraséologie », recorded at the Institut voor Psychoacustica en Elektronische Muziek studio, aka I.P.E.M., which had been the Ghent University electronic music studio since 1962.

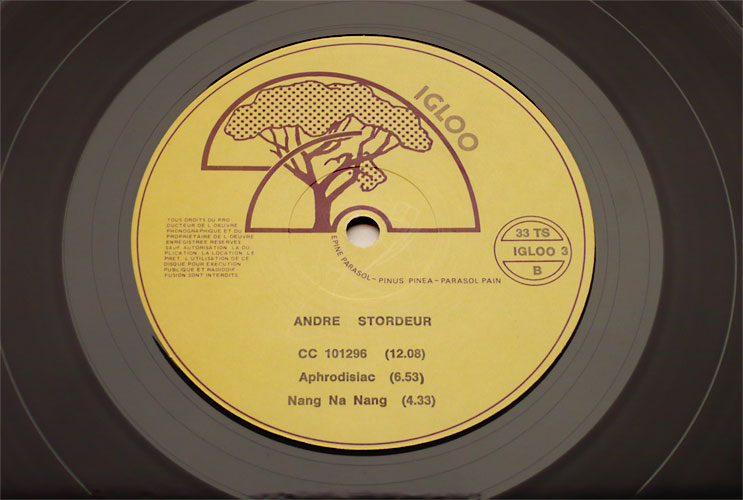

The same year, he published a solo recording titled « 18 Days » featuring compositions using an EMS AKS and a modified 8 voice patchable Oberheim SEM1 system.

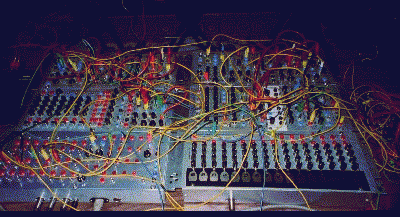

In the early 80s he started using a Serge synthesizer prototype which was especially built for him by Serge Tcherepnin himself. From 1981 on he was the Serge company consultant for Europe.

In 1981, Stordeur composed the music of Belgian film director Christian Mesnil’s documentary « Du Zaïre au Congo ». He studied at IRCAM in 1981 with David Wessel and then flew to the US to study with Morton Subotnick, who was also a familiar figure at IRCAM between 1979 and 1981. Stordeur was an influential sound synthesis teacher and, in 1997, completed his « Art of Analog Modular Synthesis by Voltage Control : a guide to everything modular ».

In 2004, he contributed one track to a Serge synthesizer revival CD titled « Serge Modular Music: Now », published by Egres, California. In 2009, Stordeur appeared on a version of Giacinto Scelsi’s Tre Canti Popolari, published by the Sub Rosa label, where he played electronic distortion of live instruments. In 2015 Sub Rosa reissued a triple CD collection of his early works : «Complete Analog And Digital Electronic Works 1978-2000 ».

Our session was kindly assembled by Michael Stordeur, son of the composer and shall pave the way to his label documenting the « lost works » of André…

We are PROUD to offer 2 powerful live recorded 40 years ago , as well as a composition for Tablas & Electronics + a little lullaby to pack it up.

He was interviewed in 2018 by Chris Ferreira…

C.F.: To quickly sum up your first musical influences before you discovered electronic music, would it be fair to include American jazz, Indian music and traditional Thaï music?

A.S.: Basically, that’s a mix of everything. I didn’t stick to any particular style, trying to create what could be my own. Starting playing Jazz, then Free it seemed natural to follow the Electronic direction since Jazz has this extraordinary faculty of generating in you extraordinary universes, something that few musics can do.

At that time did contemporary music have any resonance with you? Did you know Pierre Schaeffer or the music of Edgard Varèse?

Yes of course, I listened to them, I was eclectic enough to listen to other music but jazz was my preference at the start, notably Coltrane who was one of my gods at the time.

Yet the first attempts at electronic music have never had as strong an impact as Morton Subotnick?

Yes, but it’s personal. Morton was not particularly appreciated by many people. I took lessons with him. As my wife is American, he often came to eat at my house when I worked at IRCAM. I was lucky to know him well enough, to chat with him from a musical point of view.

Why do you think you were more sensitive to this electronic music?

When you hear the beginnings of electronic music from the sixties, there is no soul. It’s concrete music with all the coldness it generates. While Morton Subotnick managed to bring in some freshness, warmth, a language that expressed other feelings that did not exist in electronic music at the time. To try to understand and by putting itself in the context of the period of the sixties, Pousseur had started in 1958 but did not specialize in electronics, its capacities were rather turned towards the Contemporary. Let’s say that Pousseur never worked to make things much easier to understand. It was always much more hermetic structures. I, on the contrary, never wanted to approach hermetic systems that were only accessible to certain initiates. No, I am in favor of opening the doors and certainly not screw locks everywhere.

« Silver Apples On The Moon » was a shock to me. I started to reconsider my aesthetic. It was not only an emotional shock but also an aesthetic shock. Morton was the trigger. For the first time, there was a musician who made electronic music that could swing. Swing in the swinger sense and so, to me who grew up listening to jazz, being used to the swing aspect of music, it worked in full effect.

There is no one else who can do it, there is only Morton. I also really liked what Morton Subotnick’s wife, Joan La Barbara, was doing. She is a person who sings in a style called: extended techniques. It’s a bit of a singing style like Cathy Berberian in Berio’s Face.

There is another person who was crucial in my life: Diamanda Galas. She is a pianist at the San Diego Symphony Orchestra and did contemporary music and who is known worldwide for her singing style, a bit like Joan La Barbara.

She intrigued me because she had an extraordinary personality, an extraordinary culture, notably contemporary music, but not so much jazz while at the same time, being very attracted to Satanism.

Why did you decide to create your Syntheses studio. What happened during this period?

Well, I made my personal cultural revolution, I wanted to experiment on other things. I was then interested in electronic music and I started giving lessons. I obviously learned about all the techniques. I bought myself an EMS Synthi AKS, which was an instrument in a small suitcase, extraordinary for the time. We could do anything with it.

How long after you had discovered Subotnick?

More or less at the same time. It was an instrument that allows a lot of things, for example to work on feedback, feedback on feedback and other extremes. I started to experiment and I started giving lessons as I went along. It was a bit of an inventory of my experiments.

How did you learn to use this instrument?

By myself, there were no books that dealt with that. No reference, nothing. So I had to educate myself.

Synapse magazine wasn’t existing yet?

No, I don’t remember in which year Synapse originated…

In any case, you didn’t learn with the help of…?<

Later on Synapse influenced me, of course, but it didn’t originated it in me. I did self-study. Learning and analyzing things to understand all the thinking behind it because there was no book explaining the technique or how to get there. So we, the « pioneers », we were there, we discovered things. We created the path as we got to know them. There weren’t many people because it was already very difficult music to swallow.

When you bought this EMS, did the other members of your old jazz group follow you a little or did you go off on your own in this idea?

All alone and that’s the drama. Crossing the desert alone. Exploring the unknown but it was so exciting. So, I started giving lessons and I had a lot of people who took the courses. Synthese was considered in Brussels as the real experimental studio gathering theater people, singers, a microcosm of people who had nothing to do with each other. Knowledge was slowly being created in one of the only experimental studios in Belgium. I taught to the whole of Brussels’ intelligentsia in the world of experimentation. There were the dancers from Mudra, Maurice Béjart’s school, who came to my house because they sometimes wanted to have custom electronic music. I did some compositions for Mudra, from the time of Maurice Béjart. We were in a frenzy of creation, it was extraordinary. I hope one day it will come back but it is not possible anymore. Unfortunately, people no longer have the spirit they need because for the experimental one should not ask questions other than the very concept of sound: what is a sound?

And when did you start to compose?

I always tended to neglect the compositional aspect because I preferred playing live on the spur of the moment rather than thinking in hope to find extraordinary forms of expression. I was much more into action. Composing is with a pen and a sheet of paper while synthesis is really trying to find what is the right composition between different modules to achieve an end. A different approach often reaching the same result but the goal was not the same.

When do you start making songs, recording them?

I always recorded them. At the time, I had an Otari speed 38 recorder that was fantastic. I made film music, in addition to synthesis, because I had to make some money!

You recorded « 18 Days » from December 18, 1978 to January 16, 1979, you didn’t have only AKS, did you?

No, but 60% was done on AKS only.

I read here that you also use the 8 voices Oberheim SEM 1 and also a software developed by yourself on Compucolor 1?

Since there was no software at the time, you had to create it yourself. So I made the software myself in one of my first discs. There was nothing so you had to deal with it. We started to do basic coding. A song on my disc is made with Compucolor in GFA BASIC in order to generate sounds. Currently, you can buy all the softwares you want when at the time there was nothing so we had to do the coding. Compared to analog equipment, we could get sounds with 128 oscillators or 128 filters. We created things that we couldn’t create in hardware.

So already before IRCAM, the most important thing for you in digital technology was the number of oscillators?

Yes, but these are fictitious oscillators that you create. It was an intellectual enjoyment more than anything else. You can’t have 1024 oscillators, it would cost a fortune, it’s impossible. It was only for the beauty of the gesture which I think was quite elegant.

Do you remember when you acquired this Oberheim?

In 1977. The Oberheim had this peculiarity of providing sounds with an extraordinary roundness and it was a very musical instrument compared to the EMS, which was a crappy but brilliant music box.

When did your relationship with Serge start?

If memory serves me well I had met Serge in San Francisco in 1977. He was a hippie and a very creative person who revolutionized synthesizers, just like Buchla had. Serge created a synthesizer whose approach is totally different, much more creative, being based on multifunctional modules. You had an oscillator that you could filter, trigger, envelope or whatever. It was very versatile because, when you compose on a machine, you patch and, very often you say to yourself: “Shit! I no longer have patch cords. ” So, he assumed that everything could be everything and each module would be versatile enough to be able to mimic another module. For example, I have a filter but I need an additional oscillator, so I will patch it inside of itself and create the module I need. A revolutionary way to approach synthesis because we always need some module that we are missing and he made possible for us to can create this module. It’s really a constructive approach: you build your module the way you want and there are no limits.