David Lee Myers is a sound and visual artist working in New York City since 1977. He has had over fifty recordings released under his own name and also as Arcane Device by Starkland, Important Records, Cronica, ReR Megacorp, Line, Silent, Pogus, RRRecords, Staalplaat, Monochrome Vision, Generator, and many other labels. Collaborations have been produced with Japan’s Merzbow, Thomas Dimuzio, Ellen Band, Gen Ken Montgomery, guitarist Marco Oppedisano, and Dirk Serries (as VidnaObmana).

Two Albums were created with legendary electronic pioneer Tod Dockstader, and with Hamburg’s master sound manipulator Asmus Tietchens five projects have been released.

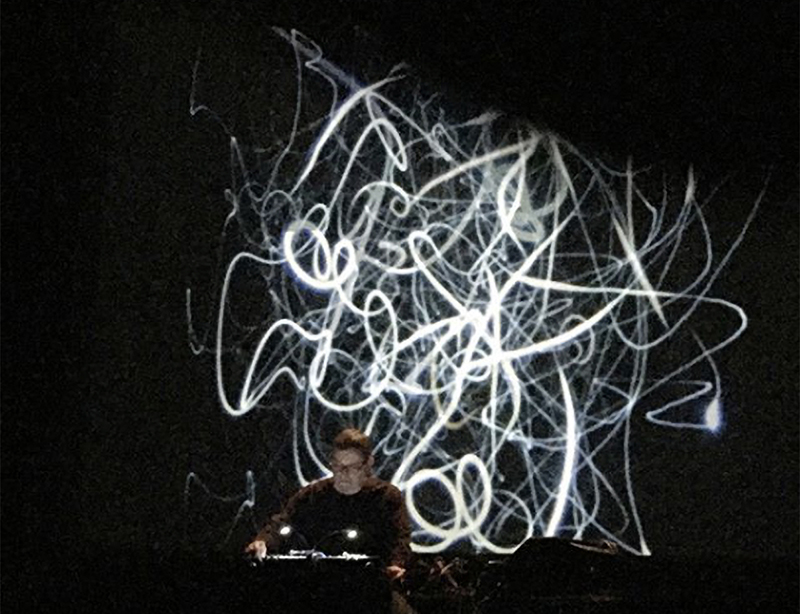

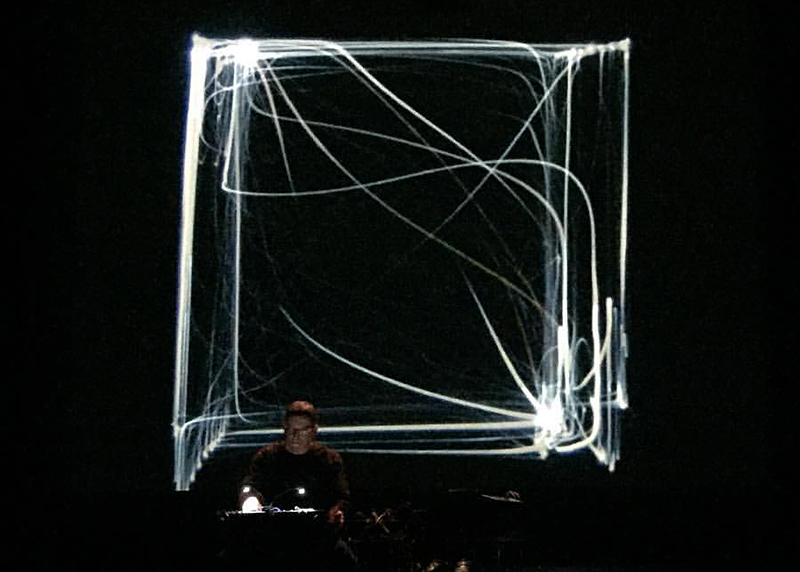

Myers has performed his sounds and visuals at New York’s Generator, The Kitchen, Roulette, Experimental Intermedia, Knitting Factory, Clocktower, MoMA/PS1, Outpost Artists Resources, Trans Pecos and Silent Barn, as well as the San Francisco Electronic Music Festival, and the Boston Museum of Modern art, among others.

You are a solitary person though you collaborate a lot.

Is music your best way to communicate?

It’s certainly a major way. But I don’t know about “a lot”—my half-dozen musical pairings stretch over several decades. I do consider putting music out there at all a meaningful stab at communication.

Decades ago you started to release music using the Arcane Device pseudonym. Can you please retrace that part of your history, summarize essential moments?

What are the musical differences between AD and using your real name, why did you switch from one to the other?

I began in electronic music in 1980 and after a few years released some cassettes as David Myers, but when I began with the Feedback Music it seemed a whole new realm. Many musicians were working under pseudonyms : Controlled Bleeding, Merzbow, etc… So I followed that example with Arcane Device, which seemed to indicate the direction the music was taking. This was a seven year period beginning in 1988. In 1995 I sold or threw away all my artworks and gear and renounced art and music in a fit of strange self-righteousness (which even today I cannot quite explain.)

By 2000 I realized that I couldn’t stay away from sound creation and began again with new feedback configurations; I am a confirmed hardware person and have a distinct distaste for creating sounds in software.

I put together several different feedback systems during this time but in 2014 I began to be aware of what was happening with Eurorack and this played a part in a rather new mindset concerning devices which led me to revive the Arcane Device moniker.

For some years now I’ve been releasing music as Arcane Device or David Lee Myers depending on… What? Mood? Some albums just seem more device-driven somehow. It’s not science.

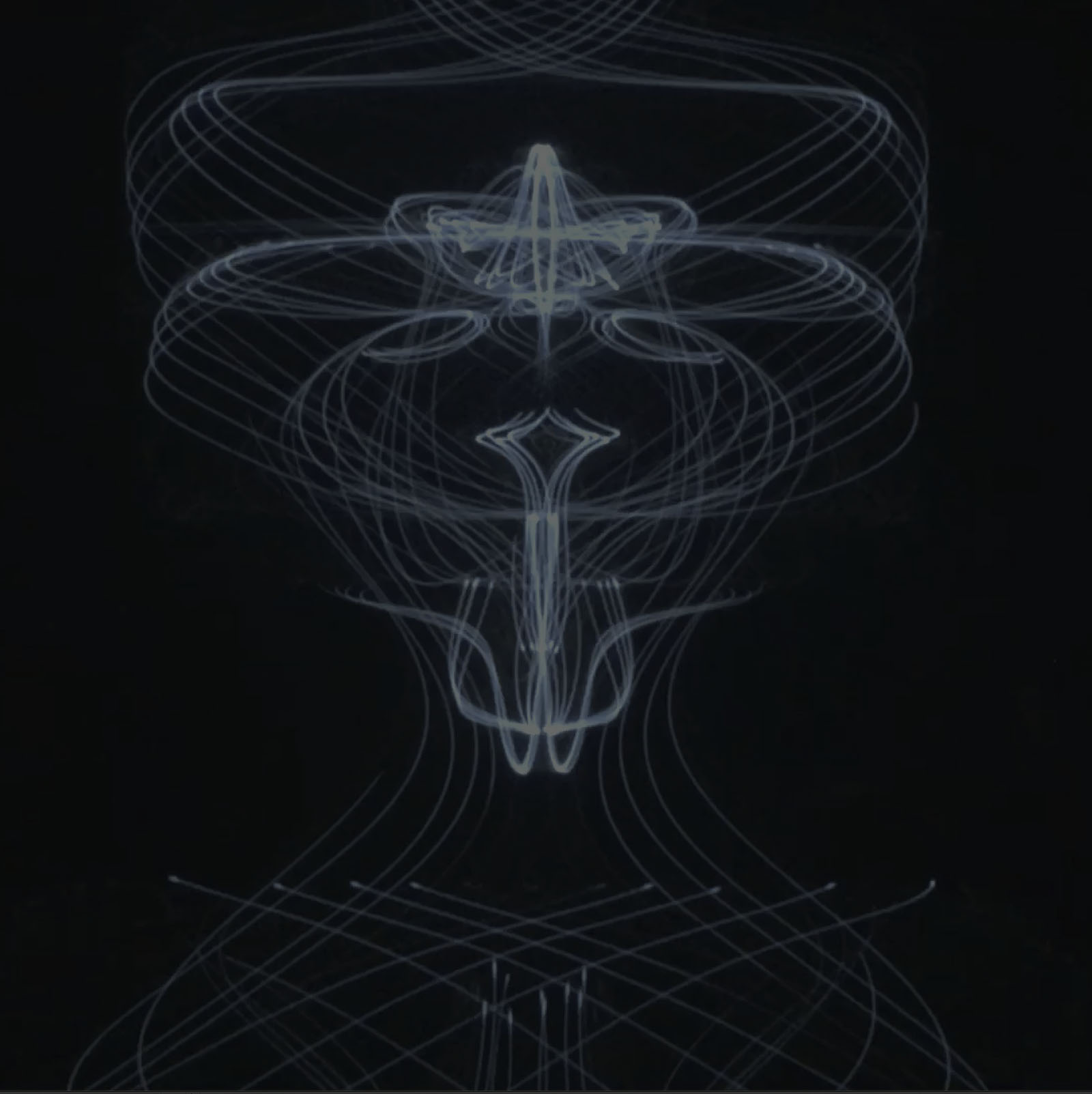

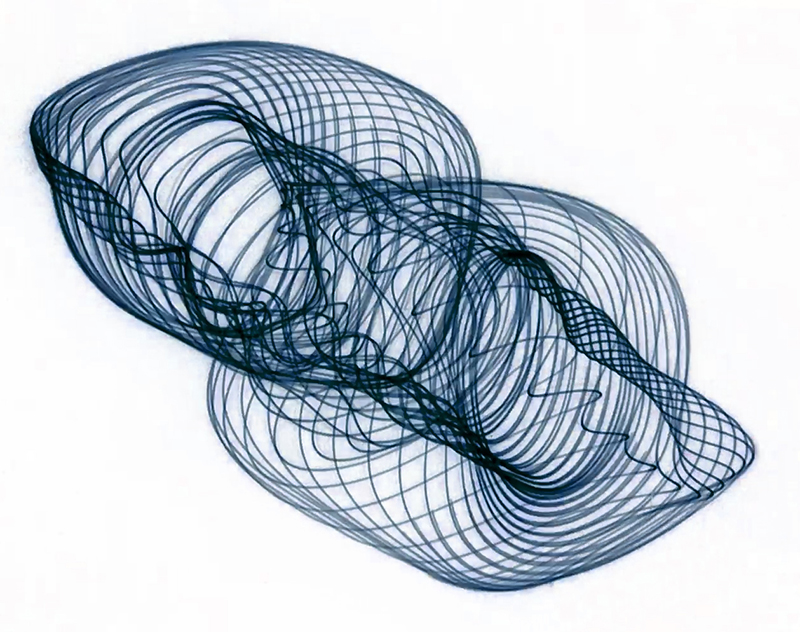

“My sound works are the result of capture, selection, processing and combination. Essentially, I do not create sounds or compose, but allow latent or unseen forces and processes to present themselves via simple technologies. I select the methods, set the stage, and as the phenomena emerge I of course introduce my own aesthetic judgements to the mix. Therefore the sounds which are presented are neither completely random science nor the gesture of an artist’s hand, but something between the two, and I believe this to be the most effective approach toward evoking meaningful impressions of unseen worlds.” —DLM

Would you please develop that quote?

To take a different angle, and referencing my works for Modulisme, the titles “Enfolding” and “Unfolding” are inspired by the ideas of theoretical physicist David Bohm regarding aspects of Quantum Theory. I have experimented along this line for some time, and the present Session represents my latest attempt.

Bohm summarizes briefly:

“In the enfolded, or implicate, order, space and time are no longer the dominant factors determining the relationships of dependence or independence of different elements. Rather, an entirely different sort of basic connection of elements is possible, from which our ordinary notions of space and time, along with those of separately existent material particles, are abstracted as forms derived from the deeper order. These ordinary notions in fact appear in what is called the “explicate” or “unfolded” order, which is a special and distinguished form contained within the general totality of all the implicate orders.”

The action of knob twiddling, switch throwing, and so on create an unseen series of atomic movements and interactions, electrons relating and developing beyond our sense perception. These then “unfold” into sound phenomena which are further “enfolded” into digital recording format, then again reappearing into the world of physical vibration. Of course my use of these ideas is purely subjective and can’t be related to any real-world principles of physics. Artistic inspiration can come from so many angles!

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

As solo as well as collaborations with others, I have had fifty-five albums released on many record labels as well as my own Pulsewidth imprint. Most of these are as CD, which is my preferred format, although virtually all are also — some exclusively — available as digital download and/or streaming on Bandcamp, iTunes, and elsewhere. Important Records has just released a collaborative CD done with noise icon Merzbow, and my “Xenography” album just came out on Pulsewidth. Regarding future plans, I have several recording projects in progress and expect more than one to appear in the fall of 2022.

Performance is another matter. I was approached in February 2020 about doing an audiovisual concert in NYC and just as I was mulling the possibility of making this one final appearance, we were hit with Covid. This was pretty much the last nail in the coffin for me regarding public display. I’m not a very public person, always biting the bullet to do a concert, but overall my randomly-generated feedback performances have always been rather touch and go and I’m not sure I will miss that. It’s likely that recordings and perhaps an occasional video or print project will have to suffice.

In 1964 Tod Dockstader was asked about performance of his music, and he said that playing his records is the performance. Especially in today’s virus-contaminated atmosphere, this seems the most viable option for me personally.

Tod Dockstader is one of my favorite pioneers, would you tell us about him? How did you meet, exchange? How did your 2 albums together shape up?

I came across Tod’s Owl LPs in a record store when I was in my last year of high school. I had been listening to Schaeffer, Henry, Stockhausen, etc., but Quatermass truly blew my mind. I forced it upon almost everyone I knew. Over years I wore out several copies of each of those albums. Then when I stumbled into my Feedback Music in 1988 it was almost as if Tod appeared to me in a vision. My “Engines of Myth” album was dedicated “To Tod Dockstader wherever you are.” I didn’t imagine I would ever be in touch with him, let alone meet him and make two albums with him.

After feedbacking for a few years I managed to reach Tom Steenland who became instrumental in rereleasing Tod’s work (on Starkland Records, which eventually did a release for me), asking him if a contact was possible. He gave me Tod’s mail address (1990s, before email) imploring me to go easy, “Tod’s a very private guy.” So I wrote Tod and to my surprise he responded very openly and warmly. We corresponded for maybe a year or two until email began to happen and on encouragement from his daughter Tina and myself, he stepped into the digital world. From then on we emailed each other almost every day for several years and he began working up sounds on his PC (not Mac, to my chagrin.)

So I “popped the question”: might we work on something together?

It came to light that we both loved frog and toad sounds—you may have heard that neighbors once called the cops on Tod as he was digging around in the yard recording the little buggers—so that became our quest on the “Pond” album. It turned out our other shared enthusiasm was movies, leading to the soundtrack butchery that is the “Bijou” album.

Our working method was mailing CDs back and forth since large file transfer did not exist in the early 2000s. It worked well enough! I had hoped we might give it another go and complete a trilogy of sorts, but Tod was slowly slipping away and “Bijou” was the last. I only met my hero one time, about 2005, when Chris Cutler and I ventured to his home in Connecticut.

Kinda fun fact: at the time he created the great Owl label records, he lived a block from my present home of forty-five years in Greenwich Village, and two blocks from Edgar Varese!

A wonderfully kind and gentle man and a true electronic music genius. I miss him.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

Well, “Switched On Bach” came out in, I think, 1968 and I was not impressed with the attempt to mimic traditional instruments in a classical music framework. My enthusiasm was and is more for the “classic studio” electronic composition of the 1950s and early 1960s. I was not making music at that time, but the release of that album did nothing to incline me in such a direction. In fact the idea of “synthesis” has always repelled me. I do not make synthesizer music and have no wish to play a keyboard. But I was curious; I’ve always been attracted to circuits and wires!

When did you buy your first system?

What was your first module or system?

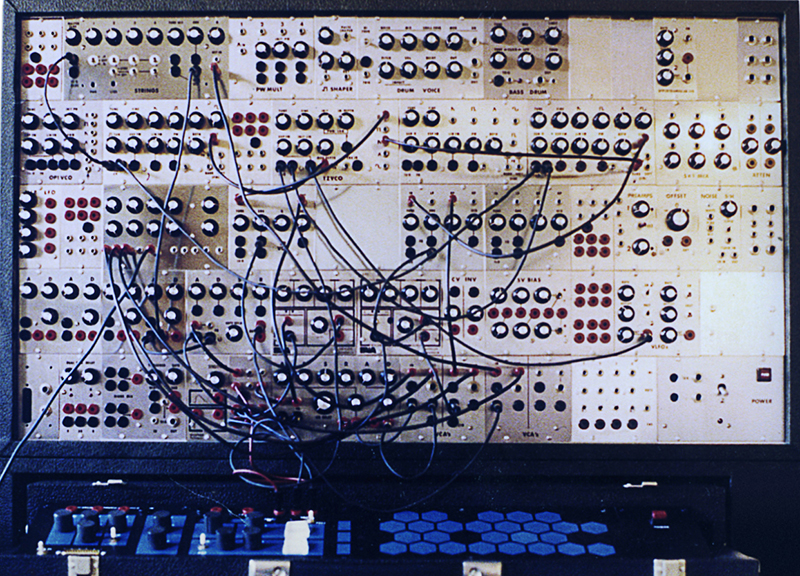

The first forays into my own electronic music were in 1980, when I realized that creating a home electronic studio was becoming a possibility. I began with kits from the likes of PAIA Electronics and gradually taught myself how to build units from scratch (I went through ferric chloride by the gallon!). By 1984 I had my first comprehensive modular system created in this manner, consisting of approximately fifty modules. This was a “modular synthesizer” in the conventional sense, and I employed it to make rather conventional music until 1987 when my perspective changed completely. I would not re-enter the modular world until 2014, while eschewing the “synthesizer” concept. As a side note: I find no further need to build my own custom circuitry, as the modular maniacs out there are designing things from outer space, and at a cost comparable or less than I can achieve.

In that year, I suppose like many musicians who become involved with modular systems, I began quite modestly with a seven module unit I imagined would be the end of it. Famous last words! I never saw this as a “synthesizer” and have rarely touched a keyboard. Even on my 1980s modular I refused the black and whites and devised my own hexpad touch controller. But I soon realized that Eurorack modular was the next step for my music. So many imaginative modules were (and are) becoming available — from innumerable creative minds and small developers — that the ability to connect them all up in different configurations at will makes possible entirely new “instruments” every day. Incredible!

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

Probably since I built everything myself in the early 1980s, I was immediately familiar with the modules’ functions and possibilities. There was no appreciable learning process.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

On your existence?

Modular systems were/are just an extension of my previous way(s) of working. A box makes a noise, the next box modifies that, they each feed the other as well as themselves. Modular makes this easier and lends a great flexibility.

Existence certainly represents an altogether different discussion….

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? How do you explain that?

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process?

Definitely. Before working with modular I would put together a certain feedback system and that would dictate the sounds and forms which could be produced. Perhaps an album or two would be generated given these physical parameters and a whole new system would be planned. With modular, the “system” is ever changing. I can have a new instrument every day. Naturally there is always the lure of a new, interesting module — and I will admit to succumbing to that — but it’s not essential to me now that my basic layout has been accomplished.

It looks as if there is a new modular company every day, I don’t know how many there are so far but it is probably nearing a thousand. God bless those creative people working in their garages and spare rooms! It must be a good business to be in since the modular junkies really are insatiable. It’s quite an addiction.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

Basically, my modular layout covers all I need to do. One major exception is the Eventide H9 which almost always plays a part in my sessions. It does everything! An expensive “pedal” but well worth it. I even bought an iPad exclusively to control it. I also occasionally make use of a Q-Mix HM-6 headphone mixer as a feedback matrix mixer, so many sends ! I might also mention that to route some recorded tracks back into the modular for further processing I quickly burn a CD and have a bare-bones CD player to feed a chain of modules. For me this is the quickest way to accomplish reprocessing at best fidelity. Seems a bit dumb, but using a sampler module or portable digital recorder did not give me results I could accept.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

My current system has evolved over years and consists of about fifty modules totaling 416 HP. For ”Enfolding-Unfolding” I used feedback from a Mutable Instruments Blades dual filter, the Q-Bit Prism, Tip Top Z5000, and MakeNoise Mimeophon, among others, matrix-mixed through a Doepfer A-138M. Previously captured feedback via a Squarp Rample was processed through two Mutable Instruments Beads modules and fed to a 4ms Dual Looping Delay, Erica Black Hole DSP2, and Eventide H9. This created basic tracks which I layered and assembled in Logic Pro. I use DAW for basically only mixing ; for some reason I am never comfortable creating sounds in a computer. I am a committed hardware man !

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

The basic approaches I see are modular, “tabletop” and computer. As I’ve said, I personally am not comfortable creating sounds in a computer; something like a fully tricked-out Ableton Live can do incredible things and I won’t criticize that, but it is not my way. I went the tabletop electronics route for years (somewhat in the vein of David Tudor, Nic Collins, etc.) and that has its special charm. But modular electronics basically takes that idea of connecting many separate elements and makes it more practical and logical. Notice that I say modular electronics, not modular synthesizers. Maybe I’m overemphasizing this, but to me, a Prophet Five is a synth and a collection of modules is something else entirely. VCO-VCF-VCA chains are something I never deal with.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

The one I have. I’ve spent a long time perfecting this and I have sworn to not go beyond 416 HP! Of course new, enticing modules appear and I may try one out, but if a new one comes in, another must go out.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists? Which ones?

I would have to mention my friend and collaborator Tom Dimuzio, who does great things with modular. But for myself, I can’t really discriminate between artists based on their methods and hardware choices. How you get there is interesting of course, but the final destination is what counts. I’m not sure Brian Eno quite fits in with this discussion, but of course he did work with modular synths at one time. In the 70s and 80s companies like Roland supplied blank “patch diagrams” for users to record their configurations. It impressed me that Eno stated that he never considered noting down patches, and this is something I am totally behind. After a session I pull all the plugs and don’t look back.

Reinvention is the name of the game for me!

« Reinvention is the name of the game for me! » and discussing collaborators brings to mind that you recently teamed up with Merzbow, who – even if I loved « Baitztoutai with Material Gadgets » as well as some of his early works – is the example of a composer who reached his perfect recipe, his comfort zone, and tends to reproduce it over and over. How do you feel about that?

Coming from the same generation, same scenes as him, how do you explain that he became favorited, so hyped and not you?

Masami has had something like four hundred releases. Can anybody expect each one to be utterly unique?

That said, for myself I certainly aim for as much variety as possible even though my palette — like anyone else’s — must have a certain limit.

It must be admitted that I have not pushed as hard as some musicians. People like Masami or Elliot Sharp, for instance, gig probably two or three hundred days a year and that doesn’t describe my comfort zone. Aside from that, music is only one part of my life and although I cherish it, there are other concerns for me.

I’m just pleased to have the fans that I do, and that anyone wants to listen to the noise I call music.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

Like many others, I would have to cite Morton Subotnick as an influential pioneer, but I was into his music long before I knew much about his methods. I did say that “Switched on Bach” didn’t do much for me, but Carlos’ “Sonic Seasonings” and “Beauty in The Beast” really got me. The latter, perhaps not overly modular as I recall ; exotic tunings took a while to come to modular.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme”?

Go to Modulargrid.net and look around, it’s a fantastic source. Muffwiggler (now “Modwiggler” it seems) as well. Perhaps find out what your favorite musicians are using. Watch lots of YouTube modular reviews. I get quite a bit of input from DivKidVideo in particular. If you know what kind of music you need to create, that should be your guide. Get a small rack and get started, for instance I try out modules and return them if I’m not satisfied. Even after return periods are over, you can probably sell at 80% original cost, consider it a rental !

Used modules are usually just fine and Reverb is full of them, including some of mine !

Good luck and make noise !