Doug Lynner is a lifelong musician whose career started as a keyboardist and guitarist in Psychedelic rock bands in the 60s.

In parallel he got a college degree in electronic music composition from the California Institute of the Arts where he studied with Morton Subotnick, Harold Budd, James Tenney, Leonid Hambro and Nicholis England.

He was the editor and publisher of Synapse Magazine, the first electronic music magazine, and is known for his “Patch of The Week” modular synthesizer video tutorial series.

Ever since the early days of Modulisme Doug has been really supportive, gracing us with one of our first Sessions :

https://modulisme.info/session/7/

Being an expert of the Serge synthesizers he helped me assemble our Serge -o- Voxes series and now it is with great pleasure that I welcome his second Session.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

I am happy to be working on a number of fronts after the inactivity of the Covid years.

The Covid lockdowns and general ill health of our world had me on the sidelines since the most common, and personally enjoyable, aspect of my music life was live performance. I wasn’t inspired to fill the time with streaming musical events and trying to keep a sense of normality and stay busy, in that way. Disquiet was buzzing in the background constantly.

The promised pieces of music that were coming due felt uncomfortable to approach in the holistic way that I have in the past where a performance is a constructed compositional/improvisational event. The relationship with the audience that I enjoy so much was just false and empty in this context.

But I didn’t want to leave my musical commitments unfulfilled either and searched for a way forward. I found two things useful, reversing my attention from whole performances to edited structures, and, defining smaller instruments that demand more fundamental approaches. They allowed me to move forward to a nonperformance world while developing some new approaches appropriate to live performance too.

The first approach led to a number of pieces including my contribution to Tone Science #6, The Mutation Trio, and this new session : Lux Solis.

The second approach led me to develop my Small Modular Aesthetic that was featured on my recent release, Red Waves. It also has served to reintroduce me to live performance and live performing.

Happily, I had my first official show in a couple of years here in San Jose. It did feature Stevie Richards from Australia, TanukiSpiderCat from San Francisco, and me. In combination had Saxophone, Cello, and Synthesizers.

I know that you had played an EMS VCS3 (Putney) in 1971. In 1973 you began to use the Buchla 200 but the first system you bought was a Serge, in 1975.

Ever since then you have remained faithful to the brand, is it because you considered the Serge sounds better + the functionality of each module more appropriate?

The Serge, and the Buchla and Putney to varying degrees, was a natural match to my musical aspirations because of structural openness. What I was hearing in my musical imagination was inhibited by keyboard controlled synthesizers because that is an event driven approach focusing on melody and I imagined an open, process oriented approach.

In the process oriented approach, Serge shines and has made itself useful to me for nearly 50 years. I haven’t fully mined it yet for all of the opportunities of expression that it offers. I think that I will stick with it a while longer.

To describe the difference between “event driven” and “process oriented” one can compare a keyboard to an envelope generator. In a traditional synth architecture, the keyboard is the control focus and the concept can be seen in the form of Serge TKBs and Buchla Wing controllers in less traditional systems too. That is, the pressing of a key, or pressure plate, instigates an event that typically includes an envelope generator that allows whatever sound is selected or programmed to be heard as well as other things. I call this “event driven” because without the pressing of a switch, the “event,” nothing happens.The key or plate delivers a pulse/gate that initiates an event.

In my world of “process oriented” composition and performance I don’t use keyboards and seldom use alternative controllers to initiate events in a way like keyboards. Instead, I usually think from the envelope/clock level out. I prefer to cycle the envelope generator, control its speed, turn it on and off manually and from other envelope generators, and have other sources voltage control it. This provides me with an ongoing process to interact with, or to negate, in the moment. I find it a much richer musical environment to realize my musical intentions in. A kind of a musical gestalt, perhaps.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

Not long. It was a natural thing for me, I think. I’m not sure why. Well, as I think about it, I was an electric keyboard player and guitarist first so I was always dealing with cables and patching audio devices in various chains such as with my effect pedals. If one is thinking, for instance, in terms of patching a pedal for distortion, a pedal for delay, and a pedal for sustain between your guitar and amp, it is not a big jump to patching modules.

And at the same time, I was beginning a critical listening habit of dissecting sounds around me for their components. So putting sounds together in a similarly deconstructed way, by patching musical functions, was also not a big jump.

And of course, because of the Serge technique of Patch Programming, patching a Serge synthesizer is not just a utility, it is an art form.

If you are me, patching is its own reward and its currency is never ending discovery. It makes you want to patch more to discover more. Exploration has continuously fueled the structured parts of my musical existence.

You had welcomed a « liberation from the traditional Western music traditions », could you develop the meaning of that?

I love western music and traditions, but, as a creative person I don’t want to just explore what our culture values historically. As wonderful as the past was, it’s not fulfilling on certain creative levels to endeavor only to recreate it and act as though you are living in the world that made it what it was.

I love the work of composers who were toiling in the direction of freeing orchestral music from its focus on melody and rhythm like Ives, Penderecki, Liggeti and others, but realistically, I could only predict that my opportunities to have works performed by orchestras would be limited at best.

I wanted to organize sounds instead of melodies. That immediately set me apart from the musical/cultural norms that orchestras primarily represent. And I didn’t want to live in the delayed gratification world of occasional institutional performances. So synthesizers looked like a practical, as well as exciting, way forward to me.

On a very different level, breaking Western musical traditions also involved immersing myself in non-Western musical traditions. I was able to do that well at CALARTS where I studied Indian, Indonesian and African music. Those traditions are now very deeply part of my compositional personality.

By seeking liberation, I expressed the need to reach for a whole musical understanding, not just the one that my culture championed and not just in the ways that they realized it.

Precise what you are after when you compose? How do you compose?

What I am after when I compose changes from time to time, from composition to composition. Maybe one time it is to expose the relationships naturally existent in a group of pitches, or, maybe another time it is to explore the narrow band between no sound and uncontrolled sound in a feedback circuit.

But, they are all united by the idea of “intention.”Intention is how I start every composition or improvisation (My works are almost always both). The intent is the idea, the point of it all. It is the goal, plan, aim, or hope that I have for my piece. Intention is what keeps me on track as I develop a piece, and intention is the bridge between the composition and what listeners take away from it, to the degree that we can actually influence that as composers.

Intention can be expressed in many ways and can be understood in even more.In my own work I use different types of intentions. Last year I did a piece, Lux Vociferatio, where my intention was far more literal and programmatic than it usually is. In simple terms, it was to represent in sound a world of light where one bioluminescent being pauses to watch two others in an animated interaction.

In the case of my recent recording, 5 Solos for Simple Slopes, my intention was to explore using one very limited patch to realize multiple instrumental outcomes and pieces. I wanted to make raw, immediate sounds that made and explored a point about limitations as an aid to creativity.

My whole album, Modular Tonalism, had the single intention to explore the patterns and relationships that exist in simple scales when explored and manipulated using modular music techniques.

I even take intention to the macro level of performance such as when I combined the feels of my two previous releases into a long-form performance at the Mormorsgruvan Rural Modular Music Festival in Sweden in 2019.

Anyway, there is a lot more to the specifics of how I compose but “intention” is always in the front of my mind.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

Terminology can become pretty important in a conversation like this. For instance, I don’t call an unpatched modular synthesizer an “instrument.” I reserve that term for what the combined patches that I make result in.

So for me, from nothing to music the terminology goes, synthesizer (machine, box, boat) > patches > instrument(s) > music/performance.

Instruments, in my terminology, are the result of various small, discrete patches combining and interacting with each overwhich “touch points” are established that are the externalization of the instrument(s).

But departing from my personal synth lexicon, “instrument building” might also refer to assembling modules in a boat, or, the DIY act of designing/building circuits both of which can be very influential in the compositional process.

Reflecting the first instance, in my work 5 Solos for Simple Slopes, the module complement/choices did reflect the compositional process and was central in the compositional intention.. The unusually small number of modules exposed the compositional intention to use module limitations to the best advantage of spurring creativity and deep understanding of the sonic possibilities.

In the second instance I first think of Louis and Bebe Barron executing the soundtrack for Forbidden Planet where they built the circuits used and many of the sounds were of the circuit’s end of life. Indeed, building the instruments became the essence of the composition.

Another way to think about this is to consider the designer as a macro-composer. Did, by virtue of being the instrument builder and designing the modules, Moog marco-write all of the pieces done on Moog synthesizers? Has Serge written, in a macro-composer way, all of the pieces done on his system? As philosophical musings these are a fun take on instrument building too.

I can say for sure that my choice of Serge technology has had a broad and continuous effect on my compositions for nearly 50 years.

Though I welcome new modules I don’t look to new modules as new solutions so much as extensions of my existing palette. For instance, the addition of a Wilson Analogue Delay has been very inspiring but has folded nicely into my existing feedback concepts rather than spurring a new line of discovery.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effects and devices when playing or recording?

I don’t use much outboard equipment. I like to have a bit of atmosphere on my output in the form of reverb and don’t have a good solution for that in my systems so in performance I use a box and in the studio I use solutions in my DAW.

I avoid all but the occasional use of outboard or DAW delay and never use any outboard processing that materially affects the sounds themselves like processor pedals. I use digital mastering to shape the profile of the final output for releases.

But that is just what works for me. My general view is that whatever it takes to realize your intention is the right thing to do. I know that I don’t feel limited by my normal choices. In the piece that I sent you for the 3rd Anniversary I used outboard delay on it. I can’t remember the last time that I did that.

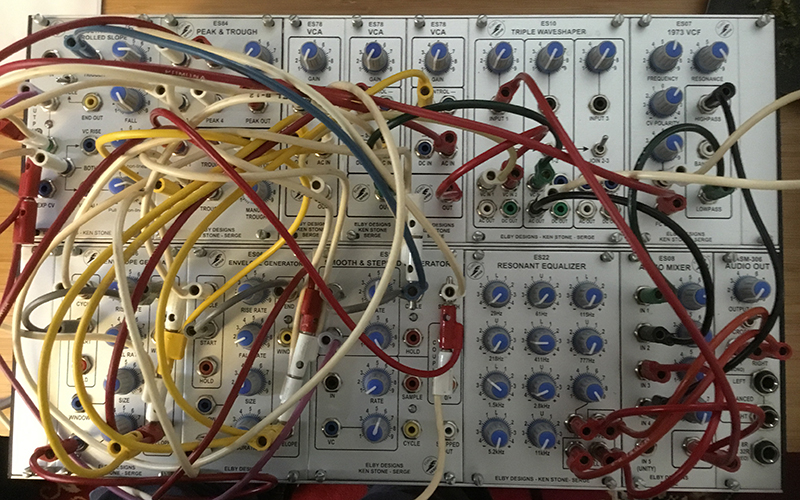

In our first interview you had said : « new modules can spark new ideas just as any change of instrument influences a composers output. » I know that lately you have expanded your system in a big way. Thus could you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Lux Solis was approached purely as a studio piece and I sourced all of my systems during the workflow of making it.

The Driskell Serge, the new expansion to my studio, played heavily in the feedback elements present in the majority of the piece.

The Elby 3u Serge Variant was used to great effect on the center sections.

The Mystery Serge was the source of many of the CVs throughout the work.

All of the systems work great together!

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes it harder to do?

One thing that comes to my mind is the split that I mentioned earlier in the interview. I am not writing from an event orientation. I work with processes. Even when the processes are organized by pitch I still approach them sans the idea of a finger hitting a key to initiate an event. Modulars are perfect in this regard because they are not typically married to keyboards or other traditional controllers.

They also provide access to the “insides” of sounds and the opportunity to make that the object of development in musical composition. This is key for my music.

Primarily, modular synths can, in the best of cases, provide an open and neutral canvas for imaging sounds.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists? Last time we exchanged you had quoted Shiro Fujioka only. Are there any others that have found favour with your ears since?

I was listening to Modular Station recently and a piece by Tom Djll came up. I know Tom pretty well and I like his music and his friendship. From many conversations at shows I know that we share many points of view.

Lachlan Fletcher, another Bay Area composer, put out a great drone project last year called Interference Patterns. A well considered and conceived work.

Øivind Olsen from Oslo is another Serge player that I enjoy. He is also part of the Olsen/Friberg Duo. I will be putting Øivind’s performance at the Mormorsgruvan Rural Modular Festival out on my Neat Net Noise label soon.

I know how important it has been for you to create or help building a community, to share, transmit. Lately you have been working on a big project around The Serge. A ressource center? Institute thing? Could you please tell us more about it?

I mentioned the Driskell Serge earlier and it is the basis of one of my new community projects. The first handful of participants are lined up and recording will begin soon.

The project, I Am Because We Are, includes Serge and non-Serge musicians using the Driskell Serge to record original works. All of the work will recognize and honor Richard Driskell, who passed away earlier this year, and his contribution to the community. The system that the composers will use belonged to Richard and was left in my hands to be sure it remained active in the Bay Area music scene. Bringing together separate parts of the larger Bay Area modular synth community in a common environment seemed a fun way to accomplish that.

Recording will begin this fall and winter.