Rick Reger is based in the Chicago area and makes music using vintage-based keyboards and synthesizers: ARP2600, VCS3, Hohner D6 Clavinet, Fender Rhodes, Mellotron Mk. VI, Mellotron M4000D Mini, Moog Voyager, Hammond organ.

From 2012-2015, Rick was a member of the Margots, with Ken Vandermark and Tim Daisy.

From 2004-2011, he played with an early version of Chicago’s House of Brunettes.

You played in various bands from Chicago, would you tell us more about your «carreer»?

Yes, “career” should definitely be in quotes because it hasn’t been a typical career.

I played piano from the ages of 12-22, including two years at the Music Institute of Chicago as a teenager, but I stopped playing entirely for about 12 years after college when I focused on becoming a professional writer. So I had almost no band experience when I was young.

I began playing piano again in 1995, and in 2005 I bought a Moog Voyager, which totally captivated me. I had some friends who had a band playing original songs, and I offered to play some synth parts on their music. That led to me joining the rock band Midwest Music Liquidators, who subsequently changed their name to House of Brunettes.

We parted ways after about six years, and I played very briefly with a couple other Chicago area bands no one’s ever heard of. But I started to experience significant pain and numbness in my hands and wrists because I had forgotten all the technique I learned in music school as a teenager. I was basically destroying my hands while playing with these bands.

I went back to the Music Institute of Chicago for two years in 2011, to relearn technique and save my hands. Fortunately, it worked!

Right as I finished with music school, Ken Vandermark (who I’d known for many years) asked me if I’d play keyboards in this band he was putting together. Although he’s well-known in the free improv/jazz world, the band he was assembling was going to play songs written by a mutual friend of ours. That band was called The Margots, and we made two records, “Pescado” and “Sople.” We played about six or eight live shows during the three years the band existed.

I had never played with professional musicians before joining The Margots, and it was absolutely one of the greatest experiences of my life. The musicians were very talented and extraordinarily supportive; the music was interesting, and I was forced to take my playing to a new level. I really cherish the time I spent in The Margots.

Around the time I joined The Margots, I bought a laptop and some Ableton software and began writing and recording my own music.

In addition to continually working on my own music, for the past year I’ve been working with Chicago-based songwriter J.R. Jones, adding keyboard parts to his music. We’ve been releasing this music under the name The Mimeographs.

You seem very active and often playing, recording in your studio. Mostly self-publishing via your BC page, aren’t you interested in trying to explore some other alleys, work with some labels, release CDs/Vinyls?

I would be delighted to work with a label. But it never occurred to me that a label would be interested in what I do, and no label has ever reached out to me. So I continue self-releasing.

I’ve started several times to put an album together and self-release it. But every time I do that, I end up a bit disappointed with some of my earlier music. I think: “Oh, I’m much more satisfied with my new stuff, so I’ll just wait a little longer and put out the album in another year or two.” Then I start to listen to my music to select pieces and the same dissatisfaction with older pieces happens all over again.

This is why a label would be helpful. I’m probably too close to the music and could use some outside direction.

You attach importance to showing/documenting how you made the song in video. Do you play live too ?

I haven’t played live so far. There’s no particular reason other than that I haven’t taken the time to learn the technology around looping and morphing chunks of music in real time.

Until three months ago, I was working a full-time corporate job that took up a lot of my time. The little time I had at night and on weekends was very precious, and it was more important to me to spend it creating new things rather than figuring out the technology around how to play live. I just didn’t care as much about the live aspect.

Now that I have more time on my hands, perhaps that’s my next focus.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

I work on new pieces non-stop, so there are always new pieces in development.

How did you first got acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

I suppose my first conscious encounter with a modular synthesizer was when I heard ELP’s “Lucky Man” on the radio when I was around 12 years old. I didn’t know what instrument created the solo at the end of the song, but I was fascinated (and a little spooked) by the sound of it.

I got very into prog rock as a teenager and heard lots of synths then, but they were mostly Odysseys and Minimoogs. I think the first time I was truly aware of what a modular synthesizer was and what it could do was when I bought “Switched-On Bach” as a teenager.

I was fascinated by synthesizers of all types at that time, but certainly the big modular synthesizers of that era were especially mind-boggling, evocative and mesmerizing.

When did you buy your first system?

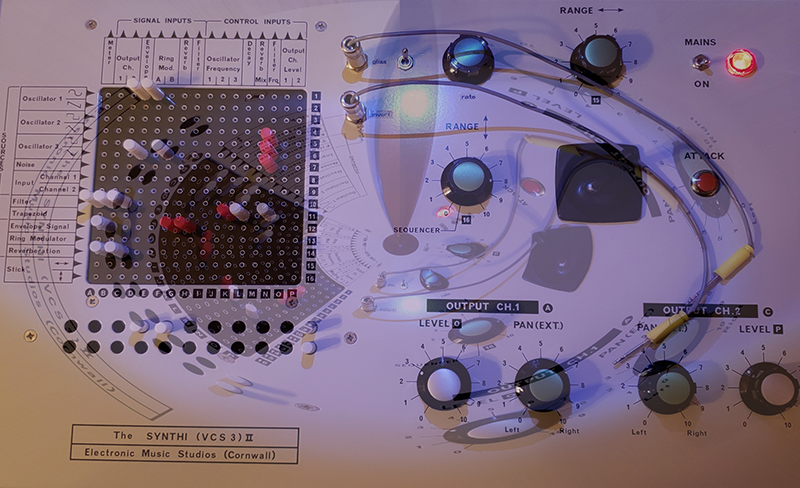

Well I’m not sure that it qualifies as a modular system, but I bought an Arp 2600 in 2006, and then I bought a VCS3 in 2017. I also own a Voyager. I don’t own what people currently think of as a modular “system.”

Have synthesizers changed your compositional process?

The experience of creating patches has had a tremendous impact on my compositional process. Once I acquired the Voyager and the Arp 2600, I was creating patches all the time, some of which were conventionally “musical” and some of which were more noise/texture/sound effect oriented.

When I started creating and releasing music in 2011, it was exclusively music that was harmony-based. But I was continually creating patches of unconventional sounds that I wanted to include in my music. Every time I tried to include these unconventional sounds in my harmony-based pieces, they didn’t fit. They sounded completely out of place. So I would take them out, and I was frustrated by that.

Then one day it dawned on me that maybe I should create pieces that were more abstract, more focused on sound for sound’s sake. So I started making what I call “Improvs,” more abstract soundscapes that finally allowed me to use my non-conventional sounds to create music that wasn’t harmony-based and that evolved in completely different ways. So these types of pieces are now a regular aspect of my work.

I have two completely different compositional processes that are each fascinating to me in totally different ways. I love that, and it’s directly the result of my patching explorations.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

I’m laughing at this question because I feel like I’m continually becoming accustomed to patching my synthesizers. For me it’s a process of learning and discovery that goes on and on. In a way, I hope I never become “accustomed” to patching them.

The first synthesizer I bought was the Moog Voyager in 2005. Although it’s not a modular system, I spent the first few years that I owned it creating and documenting new patches all the time. I couldn’t get enough of it.

What’s the effect of that discovery on your existence?

To paraphrase Rene Descartes: “I patch, therefore I am.” 😊

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? How do you explain that?

That seems easy to explain. I think many people are drawn to modular synthesis by the allure of designing your own sounds from scratch instead of relying on the familiar sounds of conventional instruments.

We are obviously living in a golden age of modular synthesis with more modules, more manufacturers and more novel options than ever before. So the possibilities that exist today for creating new sounds are practically endless.

Whose imagination wouldn’t be inspired by that? It seems to me that the endless curiosity to discover what’s in outer space, which so many people find irresistible, is analogous to the endless desire for find new sounds, textures and possibilities that drives the modular synthesis community.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process?

At this point, I’m only using pre-made systems and standalone effects pedals.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

I use outside effects with all of my instruments. I like the sound of some classic ring modulators, phasers, overdrives, reverbs, etc.

Would you please describe the instruments you used to create the music for us?

I used the Arp 2600, EMS VCS3, Moog Voyager, Mellotrons (analogue and digital), Fender Rhodes, Clavinet (played through a Ravish Sitar pedal and an Empress Fuzz pedal), a bowed Glockenspiel and a variety of Gongs and Singing Bowls.

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

Each piece began with me simply exploring and building a patch on either my VCS3 or my Arp 2600. Once I found a sound that seemed interesting to me, I recorded about 6-8 minutes of it. Then I repeated the process, only this time looking for a sound that would either blend well with the first sound I created or provide an interesting contrast with it. Then I’d record about 6-8 minutes of that sound.

I usually repeated this process until my DAW would have anywhere from 4-8 blocks of sounds layered on top of each other.

Then I would begin “sculpting” the piece by fading different sounds into and out of each other until the shape of the piece started to emerge, and I could see where it seemed to be going. Once the basic outline of the piece was in place, I would just think about what other instrumental sounds/textures might be added at certain places to give the piece more depth and narrative flow.

This was the basic process for all the pieces in my session.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

I’ve never worked with any other type of electronic music outside of modular synthesis, so it’s hard for me to assess what the limitations of those formats might be. But it seems like modular synthesis greatly simplifies the process of designing sounds from scratch. I mean, it can certainly be complicated to use a modular system, but it seems like it would usually be much easier than cutting up tape or manipulating sounds with software.

But perhaps I’m saying that because the tactile nature of modular synthesis is so immediately appealing and imparts a sense of connectivity with the instrument that those other forms may not.

In fact, I think the feeling of connectivity with the instrument is key here. I feel a genuine connection with all of my instruments, especially the synthesizers. Bob Moog talked very explicitly about how important this sense of connection between the musician and the instrument was for him and how he designed his instruments to help foster that connectivity. I think this is very important.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

I would love to have a Buchla and/or a Serge system. In terms of sound and functionality, they’re both different to what I’m used to using. So it would be wonderful to be able to explore all they’re capable of.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists? Which ones?

I’m fascinated by Eliane Radigue’s music, both because of its beauty and stillness and also because she often used Arp synthesizers, which I’m familiar with. I was very interested in and moved by the music of Richard Lainhart, who sadly passed away in 2011. He used a Buchla system in conjunction with a Haken Continuum to magnificent effect. The Haken/Buchla tandem is one I still dream of owning.

I have long admired what Suzanne Ciani does with her Buchla systems, and I’m always interested to hear what Todd Barton does on his Buchla system.

I just realized that I keep mentioning people who use Buchlas even though I don’t own one. I guess I admire the way these artists use the Buchla to create music that’s so entrancing.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

Eliane Radigue, Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Cluster, Wendy Carlos, Brian Eno, Morton Subotnick and TONTO have all influenced me (and continue to influence me) in various ways. They all used modular synthesizers in different ways and in different directions. So each in their own way helped reveal the possibilities that were available with modular synthesizers.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Just start – or continue – exploring.

That’s all I really do. I don’t have a methodology or system for what I do. I just explore and imagine. Modular synthesizers provide a wonderful platform for doing both.

Nebula:

Drone Colors:

Epilogue