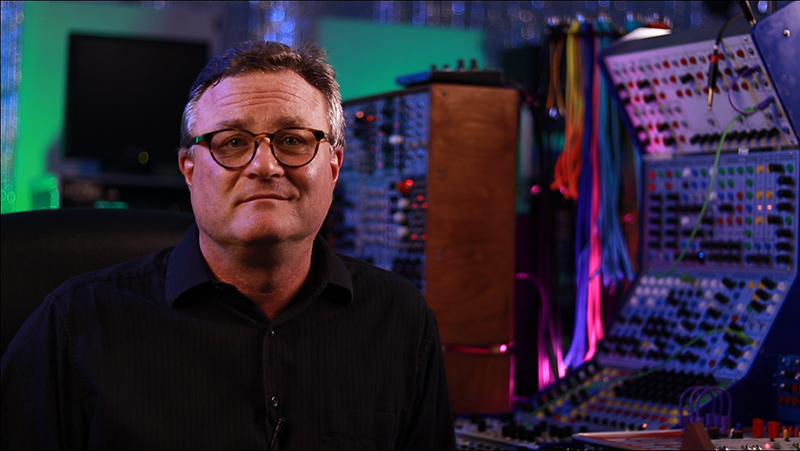

Nicolas Peck is an American composer, keyboardist, sound designer, and audio director.

He has been continuously active since the early 1980’s, and has made a living as a sound designer/composer since the late 1990’s.

Many will know of his “Under the Big Tree” YouTube channel mostly dealing with electronic music but may also have heard his music without knowing it since he has been audio director of Disney Publishing Worldwide since 2012, where he has done hundreds of projects for iOS/Android, Amazon Alexa, Google Home, and many Disney partners around the globe. He is currently focused on creating audiobooks and linear audio stories across the many franchises of Disney, Pixar, Marvel, Twentieth Century, National Geographic, and Lucasfilm.

Peck holds a BA in Psychology from UC Berkeley (1987), a BA in Electronic Music from San Francisco State University (1993), and an MFA in Electronic Music and Recording Media from Mills College (1998).

Primary music teachers included Pauline Oliveros, Maggi Payne, Chris Brown, Alvin Curran, and Herbert Bielawa.

His principle areas of study were experimental electronic music/musique concrete, modular analog synthesizers, analog hardware design, and computer music. He plays guitar, electric bass, Hammond organ, Fender Rhodes, and other electromechanical keyboard instruments + the Buchla Easel, the Kyma sound design system, Eurorack and Serge modular synthesizers.

You have been very active as a composer and audio director of Disney Publishing Worldwide since 2012. Can you tell us more about that, what type of music are you composing thru those alleys?

You also sound-design for video games?

I have been blessed to have a long career in audio production, primarily as a sound designer and audio director, but also in music composition and production, and lately, dialog recording and directing. I grew up in Marin County, just north of San Francisco, which happened to be the birthplace of Lucasfilm, Industrial Light and Magic, Skywalker Sound, and LucasArts Entertainment Company.

I worked first at LucasArts, then at Skywalker Sound, as a sound designer and game sound supervisor. To me, creating sound effects was completely related to my work in electronic music, and just as satisfying.

I later moved on to Activision, where I was audio director of a game studio that produced X-Men games and, eventually, Guitar Hero Van Halen.

After that, Disney Publishing called, and was interested in building an in-house team of audio professionals to work on projects across their enormous collection of franchises. I started the team ten years ago, and have been leading the charge ever since. It is funny that I started working on Star Wars in 1998, and in 2022, I’m still at it.

You have attached a lot of importance to teaching and the sharing of knowledge in a variety of forms, especially thru your Under the Big Tree YouTube channel. Is it important to help the « Synth community » ?

I have been mentored along the way by so many amazing teachers. I never would have found my way without their guidance, and am continually grateful that they were there for me.

Some of them, such as Pauline Oliveros and Dr. Herbert Bielawa, are gone now, and thus can’t teach directly anymore. And so the time I spend on my YouTube channel, Under the Big Tree, is to continue spreading knowledge of synthesizers and electronic music to others. I would love to just be able to teach electronic music at a university, but my life responsibilities and career at the Walt Disney Company make that dream impractical, at least for now. As a result, I try to teach by YouTube, and by occasional lectures at colleges and synthesizer conventions.

On another hand you don’t seem to care for releasing music thru traditional alleys, such as CDs/Vinyls. Why?

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

I have released nine albums on Vinyl or CD, either as a solo artist or band leader. And while I love the format, especially vinyl, making the product is only the first step. You have to market it, fulfill orders, find a place to store the boxes and boxes of records, and constantly be pushing your product. I did it for so many years – I recorded and produced the albums, wrote the music, played keyboards and sang, paid for the production, organized and cajoled the musicians to rehearse and come to the recording sessions. I really did it, over and over again, and never made any money at it.

I asked myself what was important to me, and the answer was creating whatever music was artistically fulfilling to me, and then sharing it with others who might enjoy it. I don’t make my living as a composer of art music – I make it in creating audio for commercial ventures. And that frees me to compose the music I want to when I have the time to do so.

My last compact disc, “Fire Trucks I Have Known”, was released in 2007. My son was a toddler then – now he is in high school. I don’t know that I would care about making a CD again, because of the ubiquity of digital audio on the internet. But vinyl? I would love to make LP’s again. If some enterprising record label out there is reading this and would like me to make an LP, just let me know.

Until then, I’ll keep releasing music on Bandcamp, through Modulisme, on YouTube, and in live performance.

This release, “Quatorsi,” took me the better part of a year.

Last year, I released another full-length album, “QKA”, on Bandcamp. That one was all done with a Buchla Skylab, recorded into a laptop running Reaper with some reverb plug-ins.

I’ve performed several times this year at modular events, and have enjoyed it thoroughly. I look forward to doing more in 2023.

I know that you studied music in the 90s, is that how you first got acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

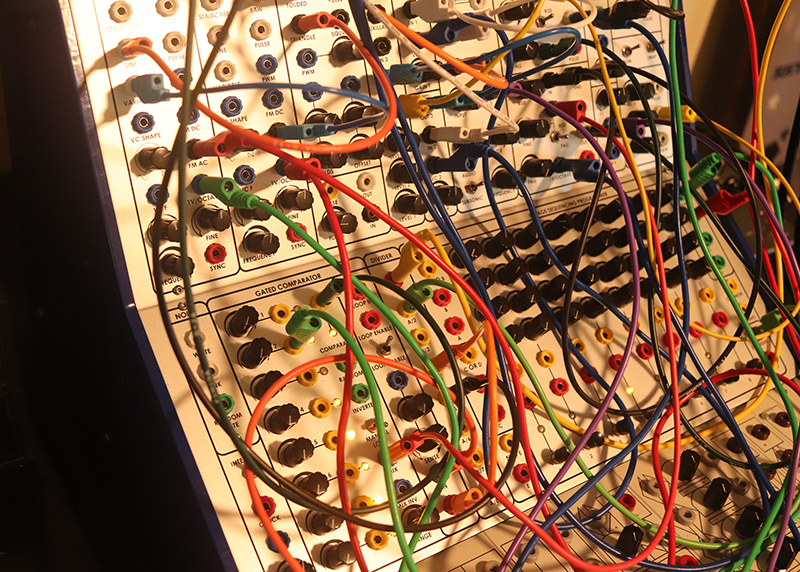

I studied music at an undergraduate level at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University. San Francisco State had a purpose-built electronic music studio, that housed a very early Buchla 100, and a Serge system made up of many Sound Transform Systems (STS) panels. That is where I first learned of modular synthesis. I thought the Buchla was very simple and sounded OK, but was primarily good for teaching the fundamentals of synthesis.

But I immediately fell in love with the Serge system. The sound, the complexity, the ability to create many sounds at the same time into a tapestry. I was spellbound, and used it all through my time at university. I did my graduate work in electronic music at Mills College, where they had the San Francisco Tape Music Center’s Buchla 100, as well as a Moog Modular. Again I used them during my time at the college. But once I was out, it was simply cost prohibitive to buy a modular system. I focused instead on keyboard-based synthesizers, as well as Pro Tools, samplers, and field recording.

When did you buy your first system?

When I first got into modular as a student, prices were just too high to even consider owning one.

Years later, I decided to try to build a 5U Mother of all Modulars (MOTM) system. I bought the kits for a single oscillator and filter, built them, and realized that the price and effort to build a usable system was still out of reach.

A decade later, I learned about Eurorack, and the world changed.

What was your first module or system?

I bought a modest Doepfer A-100 Eurorack system with all the basics, but not much more. It was the perfect way to start. Once I learned it, I was absolutely hooked, and began buying modules from a variety of manufacturers, and doing a lot of DIY kit building to expand my system.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

That is the beauty of formal education. Because I had already learned modular in a university setting, sitting down and creating with my Doepfer system was immediate. This is also one of the reasons I love the Doepfer modules. They are incredibly straightforward, with simple, unadorned graphics that don’t require learning a new visual vocabulary.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

Modular instruments are incredibly freeing, in that the process of creating the instrument (i.e. patching) is so crucial to the creation of the sound.

I love playing the piano, but variations in the timbre really come down to velocity, use of the sustain and sostenuto pedals, and the individual piano itself.

Modular allows you such a wider timbral palette, and it is the harnessing and blending of those timbres that are such a defining element of the artist’s style. For me, after years of rock bands, keyboard synthesizers, and sequencers, I learned about modular. And at the same time, my ears were being opened to Musique Concrete, Minimalism, and Experimental Electronic Music. In one year, I was exposed to Stockhausen, Boulez, Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaffer, Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley and Steve Reich, John Cage, David Tudor, and so many more.

Modular synthesis and Musique Concrete became the primary tools in my compositional toolbox, and have remained so (at least for my art music) ever since.

What was the effect of that discovery on your existence?

All of our lives can be divided into different simultaneous elements. The unceasing demands of parenting and working drain a large portion of my energy, although I love doing both.

Electronic music, and particularly modular, energize me and bring great joy to my life. I always feel great when I finish a new piece, or build a new module, or post a new Under the Big Tree video, or record a new episode of the Audio Nowcast podcast. For that matter, baking bread is very rejuvenating as well – it is all about the creative act.

There is another wonderful benefit to the modular world, though. Over the last decade, I have made incredible friends who love modular and experimental music as much as I do. We are a family.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? How do you explain that?

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process?

There is a fine line between acquiring musical instruments for their specific use, and gear acquisition syndrome (GAS).

There is certainly a dopamine hit when you get a new thing – that’s what retail therapy is all about. But consuming is NOT creating. Consuming is consuming. I have most certainly been guilty of looking for the next cool thing, and have a studio full of wonderful equipment that I have purchased over the last 40 years. But there are, of course, financial consequences to everything you buy – that is money that is not being used for other purposes, or being saved for retirement. I know that I purchased a lot of Eurorack modules in an effort to create a system that would be far better realized by a desktop hardware sequencer and some polyphonic synthesizers. That was a mistake, and a waste of time and money. But other risks that I have taken have paid off handsomely – the Music Easel being a perfect example.

One of the reasons I switched primarily to 4U was because I found that Eurorack was an endless black hole of module purchasing. No matter what you bought, there was always something better just around the corner. I see people’s systems that are a hodgepodge of digital devices from different manufacturers, requiring a lot of time and energy to learn and use musically. Personally, I have sold off a large portion of my Eurorack system, and have more modules to sell. I have boiled things down to one case of Doepfer modules, and one case of my favorite modules from other manufacturers: Mutable Instruments, 4MS, Intellijel, Music Thing Modular, plus a number of modules I built myself. It is still an incredibly powerful system, but ends up in the corner not being used much.

For me, the most important aspect of Eurorack was to get back into modular. It really ended up being a stepping stone into 4U. I now have 8 panels of Serge, a Music Easel, and a Buchla Skylab. If that isn’t enough, then it is my imagination that needs looking at, not the equipment.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

I think that modular music really benefits from some signal processing at the end of the chain.

I like to run the main mix into delay and then reverb, typically at a mostly dry setting. In my Eurorack system, that need is solved by a 4MS Digital Looping Delay going into a Mutable Instruments Clouds.

For my Serge and Buchla systems, I use a Strymon Timeline delay and Big Sky reverb. They are OK, but I have been thinking about using a Teensy 4.1 microprocessor within my Serge case, acting as delay and reverb as part of my system. It would involve both hardware and software design and is quite a significant DIY project. But there are lots of DSP algorithms out there already that I could use and modify as needed.

When actually recording music on my big system, which is a 48-input Soundcraft GB8 console and a 24-channel Radar 6 hard disc recorder, I have reverbs and delays hard wired to the effects busses: Lexicon PCM70, PCM80, and PCM90, and an Eventide Harmonizer H3000. Ancient tools that still sound great.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Well, it was a number of different systems for different parts of the piece. Some of the material was performed live in front of an audience, with additional materials overdubbed back in the studio. Other parts were sections of explorations that I recorded while performing in the studio.

There were musique concrete elements that included processed cello, drum kit, piano, and sax, field recorded elements, such as throwing a heavy box across the room, and some sounds that were created by my Kyma system. But the majority was various parts of my modular system.

The first section was my Music Easel and some Eurorack oscillators being processed through the 4MS Dual Looping Delay and Clouds, as mentioned above. The Buchla Skylab was used here and there, but nowhere near as much as the Music Easel and the Serge. There was a lot of Paperface Serge circuits, from Prism Circuits and 73-75 panels I built myself.

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

As mentioned above, some pieces were performed live with additional overdubs added. Some were created entirely in the studio, mostly by recording performances live on the modular.

The musique concrete pieces were recorded separately at different times, then processed in Reaper and Kyma, and added to the mix. I have a 1010 Music Bluebox mixer/recorder, which my modular systems run through. As soon as I find a sound I like, I hit the record button and immediately grab it on the Bluebox. Later, I transfer the materials to an ancient 2010 Mac Pro running Reaper for editing and mastering. I sometimes use my analog mixer and RADAR recorder, but it is frankly a lot of extra effort that often isn’t necessary.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

For me, it would be improvised live performance. I can’t imagine spontaneously creating a timbrally shifting and interesting work with one of my keyboard synthesizers. I love my Oberheim OB-6 and my Groove Synthesis Third Wave, but would be very uncomfortable on a stage with one of those instruments, and needing to create a cohesive and interesting piece out of nothing. But give me my Buchla Music Easel and a delay pedal, and I’m all set to go.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

I already have the system of my dreams.

I love performing live with my Easel.

I have a lovely system of Serge panels, much of which I built myself.

I have a Buchla Skylab, which I intend to supplement eventually by building some model 200 clones, such as the Multiple Arbitrary Function Generator.

I would love some Sound Transform System (STS) Serge panels, but they are very expensive and difficult to justify. But the new thing I am most excited about is a two-panel Prism Circuits Serge system I’ve designed for performing live improvised abstract electronic music. DIY is a lot of work, but that makes the finished product that much more personal and meaningful. I’m sure it will take me at least the rest of the year to build it, but it will be a lovely thing to work with in 2023.

I borrowed a two-panel Serge system that is very similar to what I’ve designed, and used it in conjunction with my Easel in a live performance recently. The two were a perfect combination, giving me everything I needed to create a multi-layered improvisation within a small, manageable, completely analog system.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Which ones?

Well, sure. I have developed quite a family of like-minded artists here in Los Angeles, and greatly enjoy playing shows with them.

There are so many, but two close friends are Skyler King, founder of Prism Circuits, and Aaron Higgins, founder of 1010 Music. We each have different musical sensibilities but love modular instruments deeply, and enjoy playing together, talking about the instruments, and helping each other out.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

I’m just going to go right to the top of the mountain. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, which was ground zero for so much development in modular synthesizers. I got my master’s degree in electronic music from Mills College in Oakland, California. That was where the San Francisco Tape Music Center was located, and where so much of this began.

I studied with Pauline Oliveros, saw Don Buchla all the time, and learned from so many other giants of new music. It was incredible to work with the earliest Buchla 100, knowing that Morton Subotnick and Pauline had made music on the same machine that I was using.

In another part of my life, I was lucky enough to work on an interactive project with Keith Emerson, who had a massive impact on my keyboard playing and my creation of progressive rock. Of course, Keith had the massive Moog Modular that he took around with him on stage until the very end.

I was very fortunate to speak to Bob Moog many times over the years, and last year, when I was in New York, I took a special trip to Trumansburg, which is where he first invented the Moog Modular. I went just to see the building, read the plaque, and imagine what it must have been like to be there in the late 60’s, inventing the tools of modern music making.

But with all that said, my first love in modular is the SERGE. When doing my undergraduate work at SF State, I’d book as much time as I possibly could in the electronic music studio, teaching myself the Serge and dreaming of one day owning one of my own. That dream became a reality in the last couple of years, when I started building my system, which has now grown to eight panels. So Serge Tcherepnin himself probably influenced me more than anyone. Thanks, Serge!

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Don’t buy too much, too soon.

You can make a ton of music with limited resources.

If you are going to do Eurorack, I would focus on a couple of manufacturers, rather than just buying whatever strikes your fancy.

Doepfer is not the fanciest, but in many ways it is still the best. You could do far worse than to create a basic analog Eurorack system using Doepfer modules.

I also love Mutable Instruments, but they are closing up shop, sadly.

Once you have worked with a basic system for a while, then spread out slowly into other products that will really expand your vocabulary.

For me, that was making the leap from 3U (Eurorack) to 4U (Serge and Buchla).

As mentioned, my primary performance instrument is my Buchla Music Easel, which is such a simple instrument, on the surface. I can improvise and put together a set with just the Easel, a delay, and a reverb.

I have seen other performers bring massive systems, which are far too complex to be able to work with in a live situation.

Less is more.