Palle Dahlstedt (b.1971) is an artist, musician, composer and researcher from Sweden.

After extensive studies in classical piano and composition, he continued into electronic music, and since the 1990s, modular synthesizers are among his main instruments, together with the grand piano. He is strongly focused on being a musician on the machines, with improvisation and physical interaction as key ingredients.

As a researcher, Dahlstedt started with a PhD in evolutionary computation for artistic creativity from Chalmers in (which also lead to the Patch Mutator in the Nord Modular). He is interested in the deep entanglement of art and advanced technology, and especially its creative and aesthetic implications.

He develops new technologies for improvisation, composition and art, and is especially interested in advanced algorithms in creative process, in technologies that allow for embodied performance on electronic sounds, and new kinds of interactions, based on a systems view of emergence from human-technology interactions. He constantly steps over into other art forms such as photography, video, visual arts and performance, and collaborates regularly with artists from theatre, poetry, dance and the visual arts.

Dahlstedt has contributed art, technologies and theories to the field of computational creativity, and has received extensive artistic research funding from the Swedish Research Council and WASP-HS. Dahlstedt is currently Professor of Interaction Design at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Gothenburg and Chalmers University of Technology, and lecturer in electronic music composition at the Academy of Music and Drama, Gothenburg. He is also adjunct professor in Art & Technology at Aalborg University, Denmark.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

I alternate between two modes of music-making: On one hand, spontaneous short experiments that sometimes, or often, result in a recording. Usually an experiment to test something, and to learn. On the other hand, I regularly do larger projects with a clearer focus and concept.

I am trained as both composer and musician, but the last 20 years or so, I have more and more focused on the live aspects. Also studio live, with no audience. So most of my recordings are two or four channel recordings from a composed system that is running, while i tweak it, or from a patch that I can gesturally play as a musician.

I have never really focused on releases in my career, but composed mostly for specific concerts or performances, or as research experiments, with a strong live focus. A very large share of my output the last thirty years has also been music for stage productions, both theatre and dance.

More specifically, I do have more recordings for sessions like this one, and I recently did a live work for audio and video synthesis together, generated from the same control voltage sources. It is called Dragonomalies. The word comes from one of the fables in Stanislaw Lem’s beautiful science fiction collection Cyberiada, which has inspired me a lot lately.

In parallel, I have a few explorative long-term projects that will take a few years to complete.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

I started learning computer programming in 1979, and structured programming is modular. I started using synthesizers in 1984, and although they were pre-configured, I explored the potentials of each module inside. I learnt audio programming in Max in 1994 on a NeXT-ISPW, and that is modular, too. The same year I was also acquainted with a large Serge system, which was the first analog modular I used, although, at the time, Max and generative algorithms was more interesting to me.

After I finished my composition degree in 1998, I heard about the Nord Modular. I called them and said “I’m your ideal customer, except I don’t have any money”. So they sold me a machine at a very good price, and we started collaborating. That changed my life, and it quickly became my main instrument and composition tool.

I used it every day and in every thing I did, and I became very active in the online community. It also became the main tool for my research, as I started a PhD exploring algorithms for musical creativity in 1999. During my doctoral research, among other things, I developed a series of tools using interactive evolution to “breed” sounds interactively. When I finished, I worked together with Nord to implement this in the Nord Modular universe, and it became the Patch Mutator, which I still use regularly in my own work.

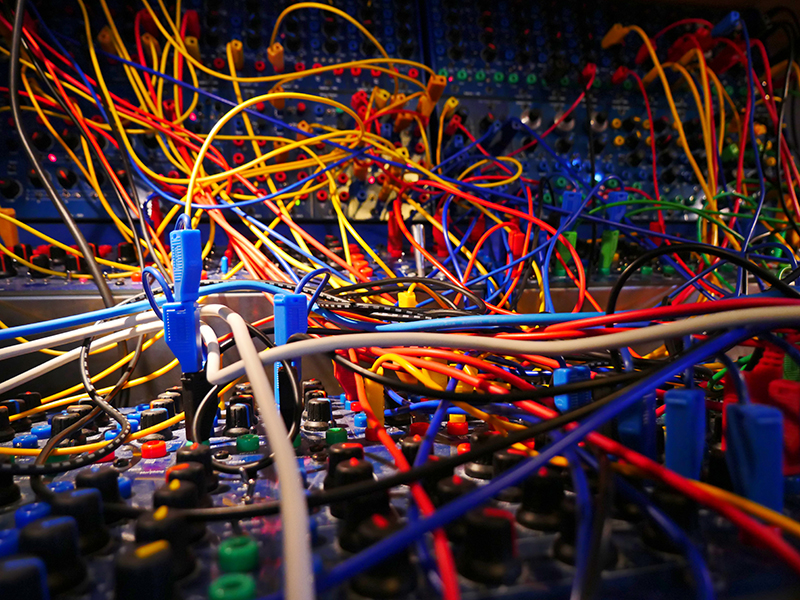

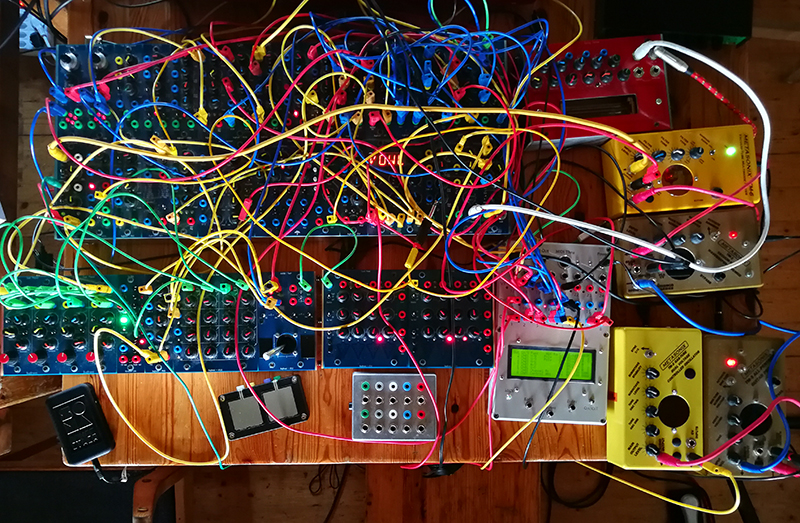

In parallel, I had a two-frame Doepfer system from 2001 and onwards, but it was a bit too uninspiring compared to the Nord Modular. I started building a larger Bugbrand bananafrac system in 2010, and since then I have focused on bananafrac, Metasonix, and I also have a eurorack system now, partly focused around live musique concrète work.

How does it marry with your other « compositional tricks »?

As I mentioned, modular thinking is a characteristic of many expressions, so I have always felt at home in the modular world, ever since I started. When working in the Nord Modular, you have total recall, which allows for a working method closer to programming, and I use the Nord Modular G2 as a broad signal processing development platform. It has been my main instrument ever since it came, and I work very fast in it, being able to rapidly test and prototype new ideas, and often I keep them in that domain also in the final version.

Using analog modulars is very different, not in how the modules are patched together, but the workflow must be different, as there is a fixed amount of resources, and as patches get built and torn down all the time. And things are impossible to repeat exactly. Much more of a constant searching, probing, and harvesting of whatever is found – in the form of recordings, and knowledge.

Your compositional process is also based upon the use of acoustic instruments that you process or combine with Electronic. How do you work to marry that Electronic with your acoustic matiere?

I am a classically trained pianist.

Until I was 21, it was officially my main subject, and I had very good piano teachers until the age of 24. I never stopped playing, but at that time I stopped performing classical works (except occasional low-profile performance with friends). Since then, I have focused on improvisational playing, and since I inherited a grand piano in 2009, I started working intensively with piano and electronics, mostly using the Nord Modular G2 to live process the piano sound, often using Moog Piano Bar sensor to capture the keyboard playing and using unconventional mapping techniques.

My firm basis in acoustic musicianship has also strongly influenced my approach to modulars. I often try to make patches that can be played gesturally and expressively in an improvisational setting, just like I do with an acoustic instrument.

I have also worked a lot with acoustic musicians, processing their sounds, live sampling them, and programming special patches and instruments based on live-capture, cross-synthesis, physical modelling, and many other techniques. As well as performing on modulars with acoustic musicians and singers.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

Already when learning my very first (borrowed) synth, a Roland Juno-106 back in 1984, I hooked it up to speakers and an oscilloscope, to learn what each module and parameter did to the sound. So I got a good understanding of oscillators, filters, envelopes, etc. from the start. My grandfather was a leading acoustician here in Sweden, and I was learning a lot from him, too.

Soon after, I got (with financial help from my grandfather) an Ensoniq Mirage (1985), and a Yamaha TX81z (1986 or 87), so I learnt sampling and FM synthesis early on.

When I started working with modulars, I think that the learning process was quite quick – at least to get up and running. I was already a quite advanced computer programmer, and it is so similar. So it was easy, sort of. I was part of the Nord Modular community, contributed a lot of patches and learnt from others, and from books. And made a large number of factory patches for Nord.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

To be able to rapidly experiment with unconventional approaches to synthesis, and not be stuck with pre-configured standard synths, was a complete revelation. I was already a composer of acousmatic music before I got deeply into modular, and the directness and experimental possibilities was mindblowing, in comparison with the more traditional and slow electroacoustic compositional studio work.

My experimentation was not only with synthesis, but also with experimental mappings and the generation of complex control structures, too.

What was the effect on your existence?

Haha, well, my existence is conditioned by modulars these days, so I must say it was a very important development in my life. They have affected the way I think, so now they are a part of my mind. Also, they serve as a great example for my philosophizing around the relationship between tools and creativity, as modular music is completely conditioned by the tool.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? You owning an impressive amount of gear, how do you explain that?

Yes, I have too much.

But I have slowed down my acquisitions now. I have often used the fact that I teach modular synthesis as an excuse to get things – I need to know what is out there and how it works. But in reality, it is my curiosity that drives me. And fear of missing out, I guess. But when you realize that you don’t even have time to explore the things you already have, it is time to slow down. The day only has 24 hours.

Do you prefer single-maker systems, knowing your love for BugBrand or Metasonix, or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs?

Certain brands are very suitable for complete characteristic systems.

Like Bugbrand, as you say, which is a complete little world of its own. Still, I combine it with other banana modules, both in bananafrac format, and with Serge format panels.

Metasonix is a very interesting brand, but you cannot really make a single-brand system out of their crazy modules, because a lot of utilities and CV sources are needed. They excel in complex audio sources and filters/shapers, and I have done a lot of music using mostly Metasonix in the signal path (such as the Tube Ration track in this session).

In similar ways I have subsystems that are focused around AJH and Frap Tools. I would love to have a Joranalogue-only subsystem, too, but currently I mix them with others.

How has your system been evolving?

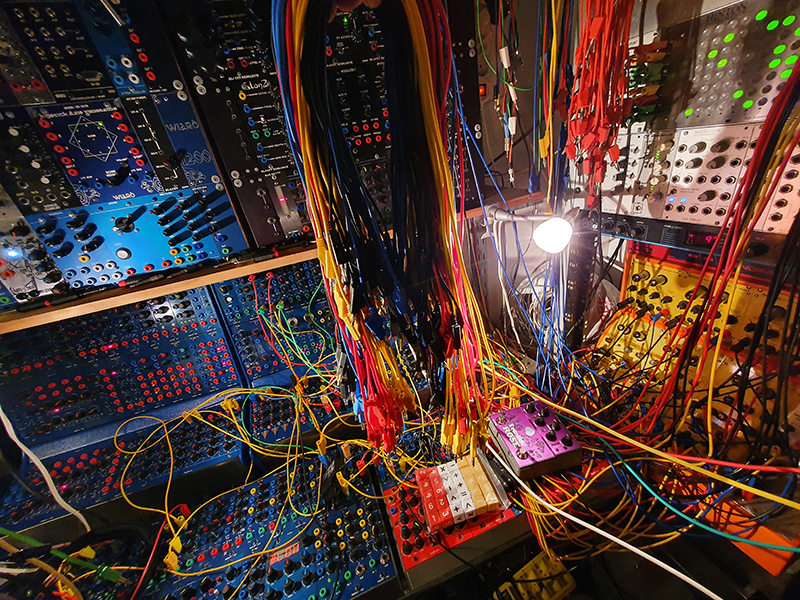

As mentioned, it does not grow so much these days. It has found its form as a modular modular, based around central library systems (one Bugbrand/Bananafrac and one eurorack) that don’t leave the studio, and portable cases with different profiles that I use for concerts and recording sessions. This is partly for flexibility and portability, but also for making things cognitively manageable. You can’t use everything at once. It’s a library of functions! I borrow here and there for whatever I want to achieve, just like you don’t use all functions in every program when coding.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

I think a lot in potentials. I am more interested in characteristic variability than in specific sequences of sounds. That is, I am more interested in a system or an instrument than in a specific instance of music that comes out of it. Exploration and interaction are key drivers in my work.

The idea of a “composed instrument” is quite established, I think. That is an instrument/patch/piece of code that embeds a large number of aesthetic choices taken at design time, and hence limits the output at play time, so that it will always be recognizable as a specific work, even if you never really play the same exact notes or sounds.

Such an instrument is to me the same as a composition.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

I stay mostly within the modular. As I have a good selection of reverbs and effects inside the modular, I am not so dependable on external hardware. I have a selection of free-standing Metasonix pedals (which are really modules) that I often incorporate in a patch, and sometimes I use external reverb (rack or pedal).

After recording, I may apply reverb, equalization and compression.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

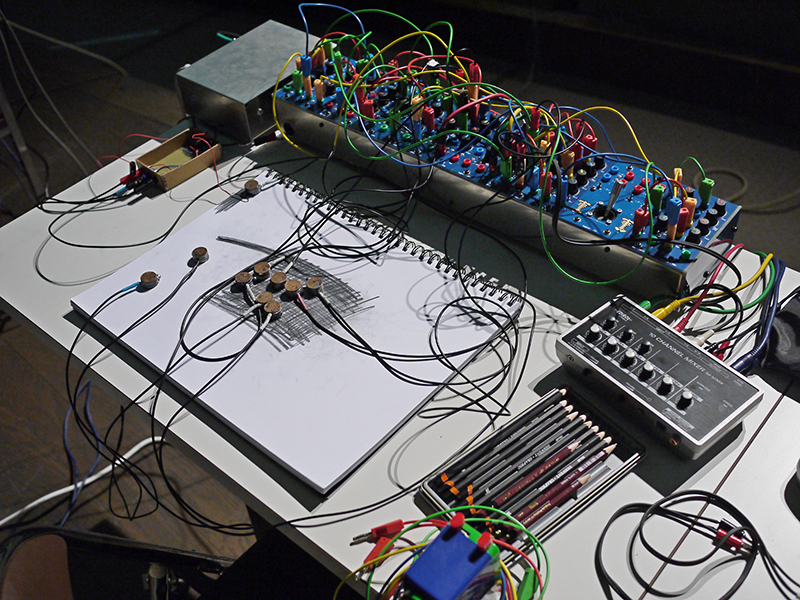

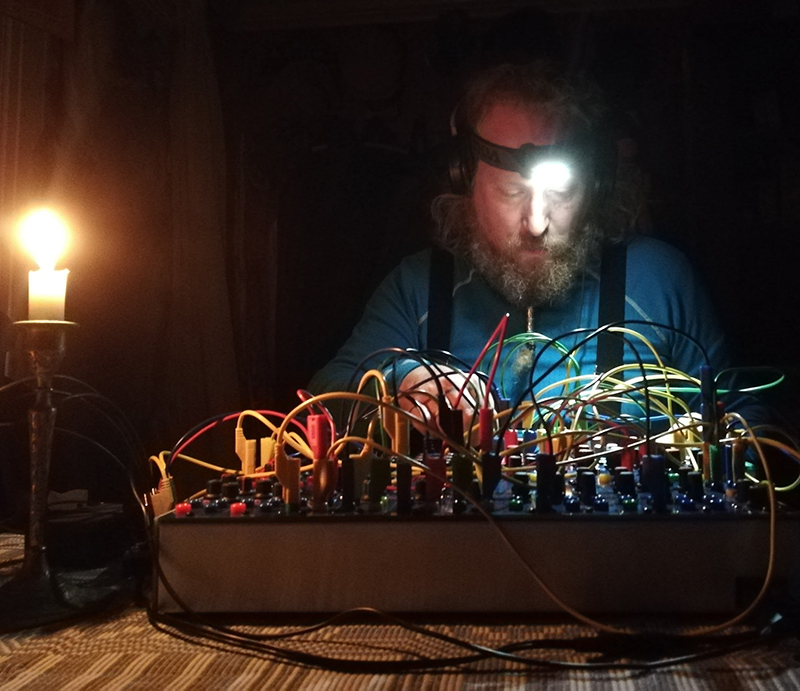

Most of the tracks (Drop Drummer, Iron Amble, Tessitura 1 & 2) were made as part of a large set of recordings on a small three-frame Bugbrand system that I brought to my mountain cabin in Swedish Lapland, where I ran it from solar-charged batteries, as I have no power there. They were recorded on a small 4-track recorder, always in one take, with no overdubbing. This system contains mostly 2nd generation Bugbrand (“New blue”) modules, and I deliberately chose not to bring my favorite module, the PT Delay (the best ugly-delay ever), to force me into other expressions. I also included one Radio Music sample player (in Bugbrand format), which is used extensively in some of the tracks, with sounds recorded from objects in that unique environment.

Tube Ration was made on my studio eurorack system, with almost only Metasonix modules in the signal path and just a few utilities, with a focus on some special time-warping techniques that create a complex rational tuning system.

Metachirp 1-4 are again mostly Bugbrand, with a few added external Metasonix modules from the TM series, and an external granular pedal.

In all these Bugbrand recordings, the DDSR module is used extensively as a structural generator, and I have worked extensively with resonant filters and phasers to dynamically shape the timbres, especially when working with samples.

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

I usually build a patch to try out a specific idea, but always end up with something that surprises me, as my brain’s predictive capacity is limited. When it is interesting and rich enough, I prepare it for recording, which may include rehearsal, some planning, but it is still highly improvisational. As an improviser, while recording I do interact a lot with the patch, tweaking and triggering things.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

I almost never do overdubbing these days, as I cherish the special form that comes out of a performance (even if I have no audience – the recorder is also an audience that evokes the same kind of flow and concentration). Still, I often record to a few tracks, usually 4, to be able to adjust the mix slightly afterwards. Often I record a stereo mix and one or two extra tracks with whatever needs some flexibility.

I rarely do any extensive edits, but when I do, it is always keeping together all tracks – so mainly master time edits, such a shortening a piece, or removing a section that didn’t work.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

Mostly pre-patched. I may move a cable or two, but usually my patches are quite complex (no holes left…), so it doesn’t work to patch them up while playing.

Which module could you not do without, or which module do you you use the most in every patch?

Haha, that changes over time. The Bugbrand PT delay is maybe my all-time favorite, but I decided to not include it in my cabin system. It is a key element in Pipes 1-4, though, which have been published as part of Modulisme Session 75.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

It is a world of its own. It overlaps a bit with the musical thinking behind Max or PD programming, which is another kind of modular music-making. And for some people it overlaps with “normal” fixed configuration synths, but for me it is completely different. I don’t think in terms of voices, and always have various kinds of generative structures and cross-modulations that is impossible to do in a non-modular.

Modulars allow for a deep integration of both structure and sound generation, without any clear division between them. Also, the pleasure of interacting with real-world objects, i.e., hardware, can never be replicated in software.

The modular at hand defines a space of possibilities, and I just love to explore that immense space.

Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

I used Reaktor a lot around 2000, but not anymore. The Nord Modular was and is a major part of my modular thinking, and I have also contributed to the Nord Modular G2 (the Patch Mutator tool is based on my PhD work). I still use the G2 almost daily. I use VCV Rack for teaching modular synthesis, as you cannot expect students to afford a hardware modular. It is a very good system these days, although a bit swamped with modules. But I recently managed to get my university to buy a classroom set of Erica Synth Pico System III, which will be a pleasure to use next time I do that course.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

I already have it. My studio is a dream system.

Well, it is so easy to dream about other things, but I try to focus on the possibilities available to me already.

They will last a hundred lifetimes.

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Yes, definitely. I work closely with Per Anders Nilsson since almost 20 years, and as I play a lot within the free improvisation community, I feel very close to Gino Robair, Tom Djll, Richard Scott, and a few others, who – I like to think – have a somewhat similar view on modular musicianship as me, with a deep background as acoustic musicians and improvisers.

Which pioneers in Modularism influenced you and why?

Oh, many. The design ideas of Serge Tcherepnin, the peculiar personality and ideas of Don Buchla (I met him a number of times, and even visited his studio), and the people around them that played and plays their instrument.

Eliane Radigue is a great source of inspiration, and I am proud to have been part of the jury that gave her the GigaHertz lifetime achievement award a couple of years ago. And as a teenager, I listened a lot to early Tangerine Dream, I have to admit. Some of that stuff I still enjoy very much. And so many others. We need to expose ourselves to the thoughts of others to evolve.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

Read the manuals thoroughly, of all modules. Learn some acoustics. Study the craft of modular synthesis – there are so many great sources available online. And try everything yourself, while reading. Hence you create good cognitive models of the modules, and can navigate more freely in the space of possibilities. You will always end up in unexpected territory anyways, but to know the basics helps so much. You will quickly build up a database of reusable problem solutions and subpatches, which is invaluable.

Also, try to explore one module at a time. That is an excellent way to learn, and most often some interesting music emerges, too.

If you cannot afford a hardware modular, start with VCV, Nord Modular Demo or some other free tool, and patch away. The knowledge you will acquire will still be valid when you start using hardware.

Happy patching.

+

+