UnicaZürn emerged in 2009 from the belly of a live-improv’ beast called The Amal Gamal Ensemble in 2001.

During the 1980s David Knight was guitarist and co-songwriter with highly influential art-pop maverick Danielle Dax, and contributed wall-of-rock guitars to the malign poetry of Karl Blake in Shock Headed Peters. He also works as Arkkon, a solo project concentrating on brooding electro-minimalist music.

Stephen Thrower’s credits include eight years in Coil, with whom he recorded the seminal albums Scatology, Horse Rotorvator and Love’s Secret Domain. He is currently one half of electro-psychedelic duo Cyclobe, with Ossian Brown. His solo credits include original electronic movie scores for Hell’s Ground (2007) and Down Terrace (2009).

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

STEVE: We have two templates for creating UnicaZürn music, both of which we’re currently using. One is for me and Dave to get together with a pile of our favourite electronic gear, and then improvise for two or three days solid. From these sessions we often end up with thirty or forty possible pieces, some of which are almost ready to release, while others provide a sort of sound library for future treatment or expansion. We then process, mix and edit extensively to bring them to fruition. The second template is closer to a rock format, with our friends Dave Smith on drums and percussion and Sam Warren on bass and treatments. These sessions tend to be more propulsive and mesmeric, with an underlying ethos closer to the ‘Krautrock’ bands of the 1970s. We’re currently working on a sequence of releases that will hopefully emerge fairly regularly over the next year.

Stephen you started playing some Industrial music in the 80s and joined in the first line up of the cult band Coil. How was it back then, can you share good anecdote, great memories? These days your main project is Cyclobe, can you tell us more about it?

STEVE: Coil was an eight-year thrill ride, and a musical education for me. Sadly it went off the rails in 1992-93. The usual story – excessive drug use and that old chestnut, ‘musical differences’.

It was always a pleasure to go into the studio with Peter and John. We recorded those early albums (Scatology, Horse Rotorvator, Love’s Secret Domain) in the old-fashioned way, booking week-long sessions in expensive recording studios. I’d been in smaller studios many times before with my first group Possession, but Coil could afford quite ‘fancy’ places thanks to Peter’s income as a pop video director. I have a very clear memory of my first session with them. We laid down “At the Heart of It All” in one take – me on clarinet and delay, Peter on piano, and John Balance on electric piano – and we were all delighted with the result. Unlike the other pieces on the first album, there were no sounds or samples arranged beforehand: the whole piece was improvised in a single take, so the mood and the pace and musicality of it emerged fully formed in the time it took to play it. Later, at the final mix stage, Peter overdubbed a track of sampled choral voices and Jim Thirlwell (producer) added a second piano track. It was the success of that first recording session that sealed my involvement with Coil, so I have very fond memories of it.

In Cyclobe (comprising me and my partner Ossian Brown), we tended to work from our home studio, as most people were doing by the 2000s, but I was able to draw on the experience I’d picked up from watching Peter in the studio. In the late 1990s, Peter, John and I put our old differences aside and we remained friends until their deaths. In their later years my partner Ossian started working on Coil’s live shows and the last few Coil albums, so we were close until the end. I always held their opinion in very high regard. They were very supportive of the work we did in Cyclobe, which meant a lot to us. Ossian and I released five albums as Cyclobe, which reached a peak I think with “Wounded Galaxies Tap at the Window”, but the gestation time of the albums grew and grew as time went on. We’ve rested the project these past few years and I now concentrate exclusively on UnicaZürn.

David, around the same time you were touring with Danielle Dax band and then participated to Shock Headed Peters. How did you guys met up and decided to join forces?

DAVID: Funnily enough, although we had both been moving in close circles, we had never met until the mid-90s, at a drink for a mutual friend who was moving to Italy. My partner Ruth Bayer had photographed Nurse With Wound and Current 93 extensively since the 80s and knew Ossian Brown, Steve’s partner. So we all got talking, hit it off, and Steve and I decided to try working together. We did a lot of home studio recording and eventually around 1999 formed the improvising collective The Amal Gamal Ensemble, a fluid group who would play at our spiritual home, London’s Horse Hospital each month with no preparation and a constantly evolving personnel. Before this I would have been perfectionist to the point of inactivity, but the regular series of performances really loosened me up and also got me to shed the musical habits I’d usually fall back/rely on – you had to continually push yourself to keep it fresh and interesting! It was a great experience. Meanwhile Steve and I continued to work on material, eventually releasing our first CD Temporal Bends in 2009.

How were you first acquainted to Modular Synthesis? When did that happen and what did you think of it at the time?

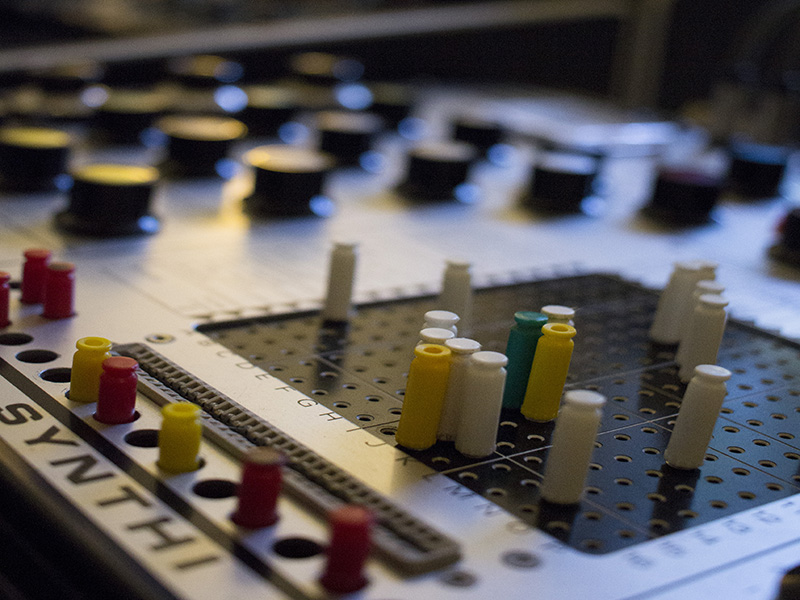

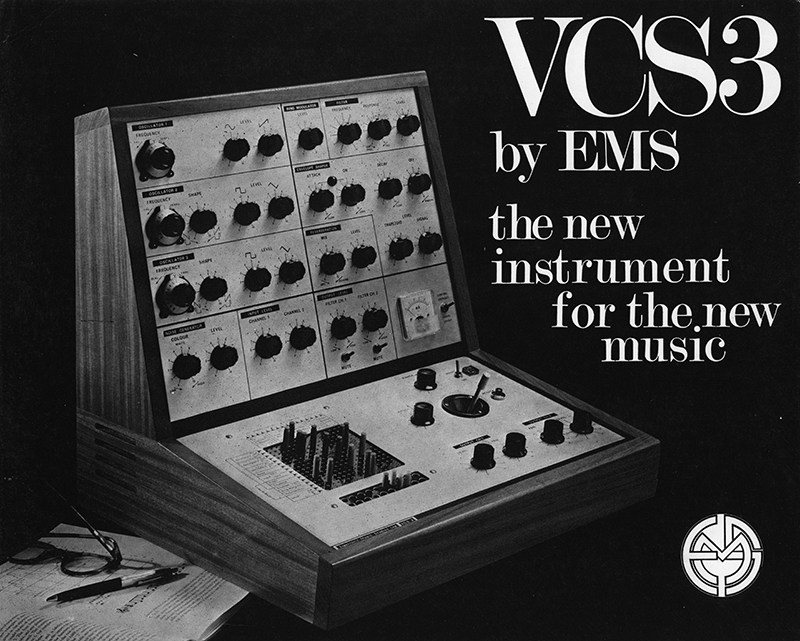

DAVID: As a teenager I had been fascinated hearing synthesisers on record – I had been a massive fan of Roxy Music and Brian Eno’s subsequent solo albums, but more relevant would be when I first heard Tangerine Dream (albums which I borrowed from the local library) it ticked all the boxes for me – in fact the first gig I ever went to was Tangerine Dream at the Royal Albert Hall in 1975, with the big Moog modular centre-stage flanked by EMS Synthi’s etc. Local Authority libraries always seemed to be well-stocked with left-field albums back in the early 70s, which was essential for discovering new music – I remember my schoolfriends and I borrowing (and taping) A Clockwork Orange OST, Tonto, Can, Floyd, Stockhausen and Berio – it was so exciting. My family lived in Battersea, and I would often cycle to Putney and stare longingly into the EMS shop in Putney Bridge Road, a single VCS3 sitting on display in the window. They kindly used to give me leaflets which I hung on my bedroom walls. I became obsessed with their gear and would study the leaflets avidly, although as I was still a schoolboy, ownership would remain a dream for a few years.

STEVE: For me the roots go back to two sources: the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Roxy Music. The early Doctor Who scores were not completely electronic (except for the title music). They would use ring modulation, delays and filters on ‘conventional’ instruments like piano, brass, timpani, xylophone, so there was a sort of merger between the timbres of the classical orchestra and the new textures of electronic sound. I wasn’t picking it apart or theorising any of this as a kid of course, but those treated ‘radiophonic’ sounds were deeply embedded in my mind as I grew up. I’d been absolutely fascinated and terrified by the early Doctor Who episodes as a boy, so the accompanying sounds ‘went in’ at a fairly deep subconscious level for me. As for Roxy Music, I loved them from the first time they appeared on Top of the Pops, performing Virginia Plain. Everything about their sound was fascinating: the fact that Eno’s synthesiser looked and sounded so extraordinary, the eccentric use of an oboe, and the sheer intensity and strangeness of Bryan Ferry’s voice and physical mannerisms. There was a brief period when punk turned its back on synthesisers in favour of a bedrock guitar-bass-drums approach, but even then The Stranglers were an exception and I immediately loved their stuff. Thanks to John Peel I heard some of the most ‘out-there’ American bands circa 1977, such as The Residents, Chrome and Pere Ubu, all of whom used electronics to add another dimension to their sound. And here in the UK, Magazine brought back the synths with a vengeance, so for me the ideal band template has always included synthesisers in some way or another.

When did you buy your first system? What was your first module or system?

DAVID: In 1977 I had bought a Hohner K1 electric piano for £100. I soon got bored with the sound of it and about a year later saw a VCS3 Mk1 with DK1 keyboard advertised in Exchange and Mart (a weekly secondhand classified ad paper) for £250 “or swap”. I called and told him about the Hohner, and amazingly he agreed to swap! I had left school and started working, so in 1980 could afford to add a new Roland System 100 (101/102/104) for the bargain price of £400. I still have the Roland, but traded the VCS3 with Robin at EMS for my current AKS about 28 years ago. It was an exciting period for electronic music – apart from the earlier experimental music I’d been listening to, punk had stirred up the scene and the new all-synth bands had started emerging – luckily, living in London I’d been going to early Throbbing Gristle, Human League and Fad Gadget gigs, and eventually I played my first gig using the VCS3/DK1 in 1979 at Mayhem Studio, a warehouse nearby in Battersea. Mayhem was where some of the first club nights which would become the whole Blitz etc scene began. I supported the Sheffield electronic band Vice Versa (later to become ABC) and pushed the gear there in a supermarket trolley through Battersea Park! Trying to tune the oscillators and keyboard octave range on a VCS3 by ear using pitch-pipes while a disco is blaring is not an experience I would recommend.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

DAVID: Because I’d been studying the EMS leaflets for so long I had a rough idea how it all patched together, but having the real thing in front of me was another story. I had the very informative Synthi manual, plus several patch sheets, which helped enormously theory-wise, but as usual with these things it was mainly trial and error.

What was the effect of that discovery on your compositional process?

DAVID: It was everything – I’d messed around with guitar and the electric piano, but they were only distractions until I got the synths. I’d had old reel-to-reel tape recorders since I was a child, and had always played around with speed change, looping and bouncing, so the synths were a natural step – and being able to sound-on-sound overdub them or create tape echo with the Akai 4000DS recorder was perfect. The ability to create (and keep) layered compositions was everything I could have wished for. I would also use the VCS3 for ‘conventional’ keyboard lines when composing instrumental pieces – it has a beautiful quality when used for melodic lines which I think is often overlooked – and before I got the Roland I used it for everything, including rhythmic pulse/beats.

On your existence?

DAVID: It gave me MY instrument – I had grown up on electronic music, and never really fully clicked with playing standard keyboard or guitar (although if I could play as well as Fripp maybe it would have been a different story – I loved ’No Pussyfooting’ and had it on constant rotation). Ultimately it changed the trajectory of my life beyond just my creative direction – without getting that VCS3 I would’t have been offered my first record deal, nor go on to meet the people who have enriched my life and surround me still.

Quite often modularists are in need for more, their hunger for new modules is never satisfied? You owning an impressive amount of gear, how do you explain that?

DAVID: I’m terrible – I’m constantly lusting after new gear under the misguided apprehension that a foot pedal will change my life as drastically as that first synth! I’m lucky in as much as most of my gear was acquired when analogue was cheap and unwanted, and I had weird enough taste to still want it. I suspect it was a case of eventually getting all the gear I had wanted as a kid – Minimoog, Solina, AKS, Synthi Hi-Fli, Roland System 100 etc. I still kick myself I didn’t buy the EMS Synthi 100 which was advertised for months in Melody Maker for £500 back in the mid-80’s – although I’m not sure where I’d have kept it…

I completely understand the urge to expand one’s sonic arsenal. An interest in electronic music is (hopefully) all about trying to seek out new and interesting sounds, so it is only natural. Of course, that doesn’t mean the person with the most equipment makes the most interesting music, in fact it’s often the opposite – I can think of many examples of artists whose best work was done when they had the minimum amount of equipment to hand – although that won’t stop me wanting more!

Do you prefer single-maker systems, knowing your love for BugBrand or Metasonix, or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs?

DAVID: To be totally honest, I’m not too worried about these things – the experience of working with the Amal Gamal Ensemble threw me into situations where I’d just pick any synth or combination of effects units immediately before leaving home and try to make the most of it. Steve and I begin the composition process solely by improvisation and sometimes to stop myself getting complacent I’ll limit myself to something as basic as a Stylophone and a pedalboard. We met Tom Bugs (BugBrand) when Amal Gamal played a live improvised soundtrack to Werner Herzog’s ‘Fata Morgana’ at Bristol’s Cube Microplex Cinema in 2005. Tom was house sound person and did a great job (as you would expect) mixing us. He told us about his units and I immediately ordered a Punch Weevil – described as: “based around lo-fi square-waves quasi-ring modulated, with power starvation & body contacts”. The Punch Weevil was thus titled as it was built into a Cuban Punch cigar box, powered by a 9v battery. I took it when I flew to Genoa with Danielle shortly after as she was performing accompanied spoken word at a poetry festival – the airport security guy told me he’d never seen anything look more like a bomb on the x-ray machine!

How has your system been evolving?

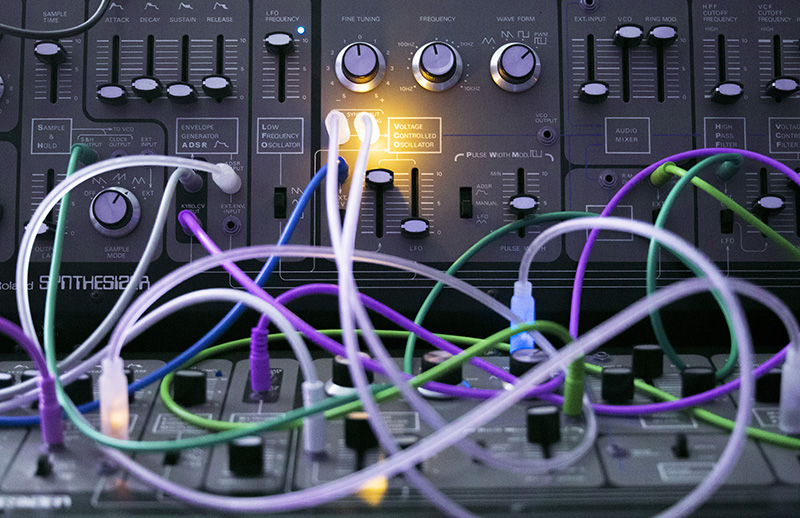

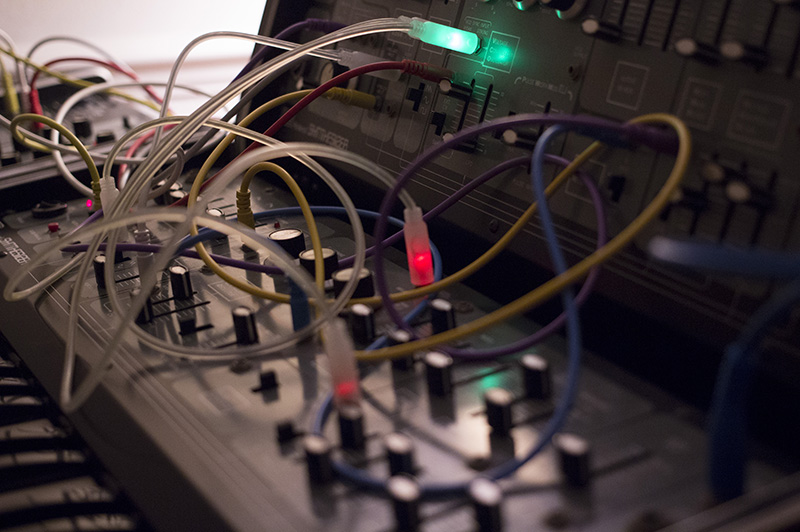

DAVID: As we work mainly with ‘prefabricated’ modular systems, we tend to expand them with external processors more than anything else – such as the Red Panda Particle granular pedal, Mooger Fooger ring modulator, a couple of the original old Lexicon JamMan 32-second delays, and the Mode Machines KRP-1 which is a wonderful clone of the 1970’s Schulte Compact Phasing ‘A’ unit, as used extensively by TD and Kraftwerk on their earlier works. For analogue delay we have a WEM Copicat IC400 – the version with vari-speed delay.

Instrument building may actually be quite compositional, defining your sonic palette, each new module enriching your vocabulary. Would you say that their choice and the way you build your systems can be an integral part of your compositional process? Or is this the other way round and you go after a new module because you want to be able to sound-design some of your ideas?

DAVID: Generally we work with what we have to hand in the moment. A lifetime of acquiring gear has given us such choice, much of the creative decision is based around what items to set up for a session – it can sometimes boil down to a 20-minute jam with Steve on string machine, and me on a tiny Yamaha PortaSound (bought for £1 at a car boot sale) fed through multiple effects. In fact that is exactly the way we recorded ‘Pale Salt Seam’ – side two of our 2017 album ‘Transpandorem’ (TOUCH Tone 57) – all we later overdubbed was an ARP 2600 to fill out the bottom end.

Would you please describe the system you used to create the music for us?

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

DAVID: As we were kindly asked to supply one hour of music, we took this as a great opportunity to create a ‘patchwork’ from our unreleased archive, glued together by parts we added live ‘on the fly’. To break down the archive recordings would be nearly impossible, suffice to say they were made up using most of the gear I have already mentioned in this interview, with the ‘glue’ coming from the AKS whirring and spluttering as only they can, and a few sequences generated by a Moog Subharmonicon, a very fun piece of gear which integrates nicely with our 2600.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

DAVID: It can be a mixture. Most pieces originate from just Steve and I getting together and playing straight into a hardware recorder. We usually spend a couple of days at a time when we get together, constantly recording – stop one, start another. They can range in length from between 3 minutes to 50 minutes usually, we then give it a few days and listen back separately to the results, and swap notes as to which ones show promise. It always involves several hours of recordings, of course. Occasionally the chosen tracks are used straight with no further work, but we often add/cross fade/overlay – and they are sometimes used as parts of a much larger piece. One thing we find we often have to do is add instrumentation in the bottom end of a piece, as in an improvisation we would generally both be playing midrange instrumentation.

Which module could you not do without, or which module do you you use the most in every patch?

DAVE: Nothing too esoteric – but one essential piece of kit I use a lot is the standalone ‘Potential’ X-Y joystick controller by LIFE IS UNFAIR. The nice thing about it is that as it is standalone I can patch it into any of the semi-modulars and it facilitates a much wider range of realtime movement and expression than can be achieved with only one pair of hands.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

DAVE: Obviously the instant hands-on ability to sculpt and fine-tune sounds is what I consider to be the major benefit. I’m a big fan of real time hands-on manipulation, actually ‘playing’ the instrument parameters, and having direct access to each parameter, plus the cross modulation possibilities. I also love Krell patches, particularly when laid over other performances, you can sometimes get some very happy accidents. To be honest with you, if I see a menu, in most situations my eyes glaze over.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

When we first began playing live UnicaZürn performances it used to be pure improvisation – we’d usually get an initial patch set up in order to get off to a ‘running start’, but from there on sound would evolve in response to where either of us felt the mood of the performance was progressing. More recently we have added extra instrumentalists at live performances – David J Smith on electronic and processed percussion, and Sam Warren on bass – it is not so flat-out improvised as it had been, so we do pre-prepare for certain pieces. It’s very exciting adding extra musicians to our mix, they are very adept improvising musicians who can take our sound into completely new realms, we have started recording improvisations with them as well, and love the results.

Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

DAVE: Although I know they are incredibly capable and have many advantages, I have no interest in software instruments. It’s a funny thing, it’s not what interested me in the first place, and as Steve said in an interview we did with The Wire magazine last year, it’s often the physicality and mojo of the actual instrument that inspires you to play with it. I remember the great drummer Bill Bruford once explaining how he likes to stick his head in a drum and smell it! I can totally relate to that – some would say it’s all about the final result, but I would guess that many musicians actually took up their instruments in the first place because of the looks and sheer physicality of them.

What would be the system you are dreaming of?

DAVE: I truly honestly believe I don’t really need any more gear! When I look at photographs of some of the people I’ve admired over the years they often have a lot less gear than we have. I think if we can’t do it with what we’ve got now, we’ll never do anything!

Are you feeling close to some other contemporary Modularists?

Which ones?

DAVE: Steve and I are great friends with Mark O Pilkington and Michael J York from Teleplasmiste, they have been working with modulars for some years now, combining their synthesis with Mike’s wind playing, on instruments he builds himself. Mike has also been doing great work with his other modular-based band Utopia Strong. Both bands are well worth checking out, they have several releases available, and play live occasionally.

Any advice you could share for those willing to start or develop their “Modulisme” ?

DAVE: Don’t feel inferior and overwhelmed by the massive systems some others have – It’s what you do with what you have that counts. There are so many cheap inroads into modular now, use what you can afford and what is available to you. The only reason I have so many old classics is because they had fallen out of favour and were cheap to pick up, plus they were the only things available which made those sounds at the time.

Enjoy the ride!